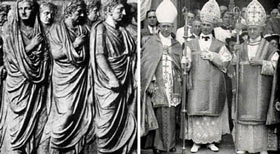

Rome's new masters

Bishops control the minds of juvenile Emperors

Barbarians scapegoated for the fall of the empire

Most of the 4th and 5th century Roman emperors were remarkably young – an inevitable consequence of combining the notion of hereditary monarchy with the use of violence as a legitimate instrument of ambition. Across the Roman world, in every imperial court – and there were now several – a coterie of bishops, female regents and eunuchs vied for influence and power. For two hundred years, seemingly limitless funds had poured into the coffers of the Church, much of it plundered from the treasuries of pagan sanctuaries. The bonanza intensified the ferocious infighting that had always characterised Christianity – Trinitarian versus Arian, Donatist versus Catholic, Alexandria versus Constantinople, Monophysitism versus Nestorianism, Milan versus Rome.

Christianity, far from unifying the Roman world with a single faith, rent division and civil conflict throughout the empire.

Rotting from the head

In Constantinople, for the next thousand years, divine emperors and illustrious patriarchs would reign in oriental splendour as lords of the earth and viceroys of God in Heaven.

Neither the sons of Constantine, nor most of the 4th century emperors that followed, had much in common with the military strongmen who had so often seized power a century earlier. The feeble sons of Constantine were followed by the equally feeble sons of Valentinian and Theodosius. Tutored from infancy by scheming churchmen, these vicious and pious adolescent emperors essentially waged civil war on their own subjects. Spending their days at court, replete with wig and face make-up, these simple-minded young monarchs – with a bishop at their ear – displayed their martial prowess by issuing increasingly vindictive edicts against heretics and unbelievers. As they laboured tirelessly (but in luxury) over such pressing issues as to whether Christ was actually God and just how virtuous was virginity, the provinces were taxed into destitution, the tax-base actually diminishing as citizens fled the towns to avoid the rapacious tax collectors.

“Old” Rome was reduced to the status of a provincial city and entered a protracted period of neglect and decline. What remained of the old senatorial class looked askance at the new Jewish god that had captured the imperial enthusiasm and whose votaries claimed an exclusivity of divine favour. Throughout much of the 4th century the more enlightened of the polytheists offered determined resistance to Christianization. But disheartened by the failure of Emperor Julian’s pagan “counter-revolution” (360-363), and the rout of Eugenius at the head of the last pagan legions (September 394), the Roman patrician class moved wholesale into the higher ranks of the Church. Financial penalties made it prudent, and penal legislation made it imperative, to abandon paganism.

And it was not all bad. The Church offered “the officer class” an alternative career to that of the marching camp or frontier garrison, one superior in rewards of status, wealth and power – and all in safety and comfort. Not for nothing did the Church model its hierarchy on that of the army; it was a fine career for a bright young Roman who preferred to fight the hordes of Satan to the horsemen of Germany or Asia. Thanks to Constantine’s “religious revolution” and the subsequent establishment of a state-endorsed Catholic Church, the manpower that might have defended the empire was drawn increasingly into the ranks of the priesthood.

Until the latter half of the 4th century the bishops of Rome had been shadowy, inconsequential figures. But in the time of pope Damasus I (366-384) – a Spaniard, suggested by some sources, related to the imperial family of Theodosius – the faith became an acceptable aristocratic affectation, with wealthy converts commandeering all the higher ranks of the church.

The successor to Damasus, Siricius (384-99) – possibly the son of Damasus – was the first Roman bishop to adopt the title “pope”, an honorific shared by all bishops in the eastern church.

What was different after the triumph of Christianity?

Again and again, supposed heresies, pagan religions and “philosophies” (that is rational thought and science) were criminalized with the severest of penalties. The repetition of the legislation itself gives evidence of widespread resistance. The populace of the empire had to be brought kicking and screaming to the Church of Christ.

The campaign to wipe out heterodox opinion reached a zenith with the reign of Theodosius I, late in the 4th century. Less than twenty years after Theodosius’ prohibition of paganism, the city of Rome fell to the barbarians. By then, the parasitic Christian religion had fatally weakened the host body; yet as the western empire died, the psychosis of “Christian faith” had already migrated to the newcomers. The barbarian tribesmen that sacked Rome and other major cities of the empire were, notionally at least, “Christian”.

Too Convenient to be True...

The classic image of “rape and pillage”. The melodrama hides the insidious and corrosive influence of the Church on several generations of weak-minded Roman princes.

It is now clear that the migrating tribes, often desperate and on the verge of starvation, had a code of morality and humanity superior to the degenerate Romans. With wagons and cattle, their movement was less of an “onslaught” than a pitiful trek.

Blame the Barbarians?

“Real-life barbarians (were) eager to settle down and savor the fruits of civilization: to defeat the enemy, tax him, visit his doctors, marry his daughters.”

– R. Wright (Nonzero: The Logic of Human Destiny)

To put things in perspective, in 410, the Visigoths of Alaric (a Christian) pillaged Rome for precisely three days before withdrawing. A generation later, in 455, Gaiseric (a Christian) and his Vandals spent just fourteen days in the city, taking what they could.

But the empire, for its part, had turned in on itself, had wasted its energies on the indulgences of a theocratic tyranny, had narrowed its vision, had ruined itself – a process that began with Constantine and his plans for a Christian dynasty.

The One True Catholic and Orthodox Faith, made secure by its establishment as the state religion, expropriated for its own purposes more and more of the wealth of the empire. Yet ultimately it became indifferent to the fate of the empire; Holy Mother Church was all that mattered.

Age at Accession and Death [BOLD]

ARIAN

Constantine I (307 – 337) – 34 (west) 52 (whole empire). With less than five per cent of his subjects professing to be Christian, Constantine endorsed Christianity as the most favoured religion. Though his Council of Nicaea was ever after hailed as the lodestone of Catholic orthodoxy, he died an Arian (at 65).

Constantine II (337 – 340) – 21. On accession in Gaul, freed the fiery “Trinitarian” Bishop Athanasius from exile and allowed him to return to Alexandria, causing problems for his brother Constantius II, an Arian. He was killed at 24 in battle with brother Constans, trying to seize more territory.

Constans I (337 – 350) – 17. Under influence of Athanasius, banned pagan sacrifice and waged a campaign against the Donatists in North Africa. Called Council of Serdica to deal with Arianism. He sold government posts to the highest bidder and was murdered by his army chief at 30.

Constantius II (337 – 361) – 20. On accession, he murdered many of his own family. Early in life influenced by presbyter Arius and his supporters.

“Vain & stupid… he bankrupted the courier service by frequent calls for Church Councils.” (Ammianus).

Terrified of sorcery, Constantius persecuted “soothsayers and Hellenists.” However, shortly before his death at the age of 44, Christian monks were exempted from all public obligations.

Julian the Apostate(360-363) – 29. As a boy, escaped the murder of his family at the hands of his cousin Constantius. Instructed by bishops but, in secret, rejected Christianity. Made Caesar in 355, Augustus in 360. In vain, Julian attempted to restore religious tolerance and the ‘old gods.’ Assassinated at 32.

Valentinian I (364 – 375) – 43. With Julian’s murder (and the death of Jovian), this stolid soldier made emperor. Issued edict forbidding pagan officers to command Christian soldiers. He was impressed by Ambrose, whom he made praetorian prefect of Italy, governor of Milan and bishop. Little interested in religion but hostile to the old pagan aristocracy, which cleared the way for Christian ascendancy. Died in a fit of anger, at 54.

Valentinian’s biggest mistake was making his obtuse brother Valens (364 – 378) co-ruler in the east (at 36). A zealous Arian, Valens ordered mass book-burning and persecution of non-Christians throughout the Eastern Empire. His arrogance led him to defeat and death at the hands of the Goths in 378 (aged 50).

Gratian (367 -383)– 8. Elder son of Valentinian. Tutored by Ausonius, a Christian poet from Gaul. No interest in the rigours of military life; withdrew his capital from Trier to the relative safety of Milan; held in contempt by army; murdered at 24 by Magnus Maximus (usurper emperor of the western provinces). Catspaw of Ambrose while he lived (abolished Vestal Virgins, removed Altar of Victory). Preferred hunting to ruling.

Valentinian II (375 -392) – 4. (Regent: Empress Justina). This child prince, the younger son of Valentinian I, relied on Ambrose to negotiate with Maximus and remained a pawn in the power struggle between the Catholic bishop and his Arian mother. Intervention by Theodosius saved his throne, only to leave him under the thumb of generalissimo Arbogastes. Refused appeal to restore Altar of Victory. Murdered (suicide?) at 19.

Theodosius I (379 – 395) – 32. Sacked from the army by Valentinian I for cowardice; his seniority led a desperate 19-year-old Gratian to appoint him co-ruler for the east after death of his uncle Valens at Adrianople. After a near-death experience at 34, he emerged as Catholic fanatic. Manipulated by Ambrose he issued draconian anti-pagan laws (any disagreement with Christian dogma was declared “insane”). Libraries looted and burned. Temples closed and burned. Appointed general Stilicho as ‘governor’ in the west for his younger son Honorius. Died at 49. Disastrous legacy.

Arcadius (395 – 408) – 18. Elder son of Theodosius ruled ineffectually under praetorian prefects Tatian, Rufinus and Anthemius, chamberlain Eutropius (who appointed John Chrysostom patriarch) and forceful wife Eudoxia (who deposed Chrysostom). ‘Withdrew’ on her death, rarely leaving palace. Urged the Goths to invade Italy to save his own skin. Compensated for weak character with pious acts of religious intolerance (ordered that paganism be treated as “high treason” and any remaining temples be demolished); died at 31.

Honorius (395 – 423) – 10. Younger son of Theodosius murdered his protector, the brilliant general Stilicho, in 408, out of petulance and envy, paving the way for capitulation to German tribes migrating into Spain, Visigoths into southwest Gaul, and the loss of Britain. The feckless and timid youth abandoned Milan and Italy to the Goths while he cowed in Ravenna. Stirred himself to call a synod of bishops and rule in favour of Boniface against rival pope Eulalius and tried to get Theodosius to return Illyricum sees to papal authority. A synod in Carthage declared the study of pagan books prohibited and issued an approved “canon” of the Church. Honorius died at 38

Theodosius II (408 – 450) – 7. (Regent: Empress Pulcheria) Early life of the only son of Arcadius was dominated by his resolute and pious sisters, his ambitious and pious wife Aelia Eudocia (whom he married in 421), and the prefect Anthemius (who built the walls of Constantinople). Many edicts of intolerance were issued in his name.

While the young Theodosius pondered the nature of Christ, his eldest sister, the Empress Pulcheria, did much to advance the cult of “imperial mystique”, and in her brother’s name banned pagans from public and military posts, and ordered destruction of synagogues and temples. She also deposed Nestorius and returned the bones of John Chrysostom to Constantinople. In June 423 Pulcheria declared that the religion of the pagans was nothing more than “demon worship” and ordered all those who persisted in practicing it to be punished by imprisonment and torture.

Her emerging rival, the emperor’s wife Eudocia (ironically, daughter of a pagan philosopher) not to be outflanked in piety, went off to the Holy Land in 439 and returned with “important relics” to boost her own prestige. Eudocia was eventually forced into exile in Jerusalem, where, in a new tactic, she embraced the cause of “monophysitism” later adopted by Theodosius II. When Theodosius finally escaped female fetters, he disastrously gave in to demands from the Huns for ever more gold and conceded to the Vandals a fully independent kingdom in North Africa.

Concentrating on really important matters, Theodosius convened the Council at Ephesus in 449 (“The Robber Council”) and declared for the monophysitic position that “Christ had only one nature and it was divine” – alienating Pope Leo I. This infamous book-burner died at 49 – falling from his horse! The Codex Theodosianus preserved his name. His scheming sister, Pulcheria, married his successor, Marcian.

Valentinian III (425 – 455) – 6 (Regent: his mother Empress Galla Placidia). Owed his throne to intervention of Theodosius II in western politics. A religious fanatic, under the influence of astrologers, he was subservient in turns to his mother, generalissimo Aetius and Pope Leo I. Lost the provinces of Africa, part of Spain, much of Gaul. He murdered Aetius, the last able general in the west, and was himself murdered at 36.

Julian jettisoned his purported Christianity the moment he became Augustus.

His reign terrified the bishops. He was assassinated (probably by a Christian soldier) within three years.

Sources:

Related Articles:

Better days … Rome vanquishes the barbarians.

Rome had been able to resist, defeat and conquer barbarians for a thousand years.

Barely sixteen years after the triumph of Christianity as the ‘one true religion’ Rome fell.

A change of clothes for the Senate

Foolish

Grey eminence of Milan

Chicken

“The amusement of feeding poultry became the serious and daily care of the monarch of the West.”

– Gibbon (Decline and Fall, ch. 29)

“Uncomprehending that his favourite chicken had perished, Honorius was relieved to learn it was only the city!”

– Procopius, History of the Wars (III.2.25-26)

Western Emperor Honorius – more concerned for a hen called ‘Rome’ than a city!

The 26-year-old and his court were hiding in Ravenna as the Goths ravaged Italy and sacked Rome in 410.

Power behind the throne

438 Pulcheria receiving the ‘sacred bones’ of John Chrysostom back into Constantinople.

(After the Proclamation in Rome of the Christian Faith)

Thou hast conquered, O pale Galilean; the world has grown grey from thy breath;

Though all men abase them before you in spirit, and all knees bend,

I kneel not neither adore you, but standing, look to the end.

Though the feet of thine high priests tread where thy lords and our forefathers trod,

Though these that were Gods are dead, and thou being dead art a God,

Though before thee the throned Cytherean be fallen, and hidden her head,

Yet thy kingdom shall pass, Galilean, thy dead shall go down to thee dead.

– Algernon Charles Swinburne (1837-1909)