Trials and Errors

The SIX trials of Jesus

Theology as drama, masquerading as history!

The Gospel of Mark’s “two stage” trial of Jesus – first, condemnation by the Jewish council, on the charge of blasphemy, followed by the Roman governor’s crowd-pleasing order for his crucifixion – is an instructive example of gospel economy: the text is terse, almost cryptic, with barely enough words for even a skeleton of narrative to hold together. In Mark, the trial of Jesus is reported in just two paragraphs, barely twenty sentences or three-hundred and sixty words. In fact, there is no genuine trial at all. The council had already decided Jesus must die, prior to his arrest. In contrast, the Roman governor almost immediately concluded that Jesus was innocent and should be set free!

To make a coherent narrative, the faithful draw on the later – and quite different – accounts of the other evangelists, versions based upon Mark’s text which add a detail here, an explanation there. But the combined narrative is overloaded with far too much coming and going and blatant contradiction and what amounts to six “trials” between nightfall and noon the following day!

The story is wholly unconvincing to the rational mind, that reads not history, faithfully recorded by eyewitnesses, but a contrived dramatization of a theological agenda, rife with inconsistency. Yet, as ever, the believer selects his own narrative from the plethora of conflicting testimony, the imagination of faith resolving all difficulties and supplying from his own mind what is lacking in the texts.

Mark: The King must Die!

Mark wrote a consoling story in which the death of Jesus atoned for the sins of Israel. Through him, all might rise again. For Mark the “trial” of Jesus was the final, pre-crucifixion scene of his drama, when Jesus faced his detractors. It is nothing more than a theatrical charade: the dramatization of a fictional event that could have only one – a theological – outcome: The king must die.

That was the divine plan. God himself, in the form of his own son, made an atoning sacrifice, a death that redeemed mankind. The betrayal of Jesus by one of his chosen intimates was itself part of the divine plan. Things could not have “gone another way.”

Mark wrote not of “historic” events that could have unfolded as the chance outcome of human choices and venal motive. The humiliation of the saviour and his terrible sentence had been preordained by God, the sacrifice had been long foretold in scripture and remained imperative for mankind’s salvation.

Evidence of “testimony” or even the semblance of a regular trial were quite unnecessary. All that was necessary – and the only reason for a trial at all – was that the real guilty ones must implicate themselves by pronouncing sentence on the Just One.

And who are the real guilty ones?

Mark made that abundantly clear, despite the brevity of his story: the Jewish priesthood – and the mob influenced by them.

“The chief priests and the scribes were seeking how to arrest him by stealth, and kill him ...

The chief priests and the whole council sought testimony against Jesus to put him to death.” – Mark 14.1-55

The crowd shouted all the more, Crucify him.” – Mark 15.14

At the same time, Rome – in the personification of the governor Pilate – would judge Jesus innocent and Rome would be exonerated, even though it acted as the instrument of God’s will. Pilate, intimidated by the baying Jewish mob, “delivers up” Jesus for crucifixion. But those culpable for the death of Jesus are clearly the Jewish leadership and the Jews who follow them.

Before the Sanhedrin

“And they laid their hands on him, and took him … and led Jesus away to the high priest and with him were assembled all the chief priests and the elders and the scribes …” – Mark 14.1, 53.

Mark’s courthouse micro-drama begins with Jesus arraigned before the whole of the Jewish council. Yet bizarrely, it is far into the night on the eve of the Passover festival (aka the first day the Feast of Unleavened Bread). Why has the council left the seizure of Jesus so ridiculously late? In fact, several days have passed since the supposed disruption of the temple traders by Jesus and the resolve of the priests to destroy him. Why the delay? Mark himself anticipated this awkward question and he has Jesus himself verbalise an answer: “Let the scriptures be fulfilled” (Mark 14.49)!

Mark’s nocturnal kangaroo court – no legitimate capital trial could have taken place at night – had Jesus standing before an unnamed high priest, all the chief priests, the elders and the scribes. They are the spiritual and social leadership of the Jews. The whole council, emphasises Mark, had already determined to put Jesus to death and merely “sought testimony against him.”

How did Mark know this? Only because he was the author of the tale.

The sentence upon Jesus was certain but the precise nature of the charges remained unclear. No witnesses for the defence were called and the “false witnesses” floundered by disagreeing with each other. Yet even so, “some” of those witnesses were able to agree something that accorded reasonably well with earlier dialogue voiced by Jesus: several references to “rising in three days” (comments that had puzzled his listeners at the time); and words spoken by Jesus in his “Olivet discourse” only shortly before:

“We heard him say, ‘I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and in three days I will build another, not made with hands.'” – Mark 14.58

“Jesus said to him, “Do you see these great buildings? There will not be left here one stone upon another, that will not be thrown down.” – Mark 13.2

False witnesses or not, the high priest referred to their testimony, and asked Jesus to respond to the statement given by “these men“.

The author of Mark gave no impressive response from Jesus – but why would he want to? His template at this point is Isaiah:

“We heard him and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is dumb, so he opened not his mouth. By oppression and judgement he was taken away.” – Isaiah 53.7,8.

Thus Mark’s Son of Man “made no answer” at his judgement.

In this ersatz trial, threats of destroying the temple were forgotten. Instead, Mark had the high priest pose the pivotal question: “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?” The Jewish priest was here used to articulate a later Christian statement of faith because claiming to be the messiah was not of itself blasphemous. Nor was it blasphemy for a Jew to claim to be “a son of God” – they were all sons of God, made in his own image! But the two epithets presented together as a claim to be the unique “messianic son of God” could be construed as blasphemous. Even so, Jesus hadn’t “cursed God”, which the law required for capital punishment (Leviticus 24.15-16, death by stoning).

Jesus barely moved his lips to confirm the charge: “I am.” A short scriptural quote followed (“sitting on the right hand of power” derived from Psalm 110.1 “Yahweh said to my lord, sit at my right hand“) and “son of man coming in the clouds of heaven“, copied from Daniel 7.13 “With clouds of heaven came one like a son of man.“)

With the apparent confession by Jesus of his blasphemy, “they all” condemned him as “deserving death” and some members of the Sanhedrin even struck and spat on him (all unlawful acts).

Before Pilate

Having described a very problematic night-time “blasphemy trial”, Mark moved the story on to the next morning when “the whole council consulted” and then sent Jesus, a bound prisoner, on to the Roman governor for a second, “civil trial”. Why a second trial was necessary Mark does not explain, though the assumption is that the Sanhedrin did not have the authority for capital punishment. This restraint was made overt only in the later gospel of John (18.31).

The hearing before the council had been brief – but the morning interview before Pilate was even briefer. Supposedly, the accusations made by the chief priests before the governor were “many” (15.3) although Mark failed to mention a single one! Instead, the trial hinges on a single question from Pilate himself, and not one raised in the earlier trial: “Are you the King of the Jews?” This straightforward question from the Roman elicits a terse and evasive response from Jesus: “You have said so.“

The reader is left to imagine that the Jewish priests, in private consultations with Pilate, have emphasised that a claimant to messiahship, ipso facto, was a would-be king, and therefore a political threat to Rome. But Pilate was not so easily persuaded. At first, he merely “wondered” (15.4) and later “he perceived that it was out of envy that the chief priests had delivered him up.” (15.10). This “perception of envy” was the peg on which Mark would absolve the Roman. So reluctant was Pilate to find Jesus guilty that the prefect argued repeatedly with a Jewish mob baying for Jesus’s crucifixion. But at length Pilate gave into the mob, delivered up Jesus for crucifixion and released a known “rebel, insurrectionist and murderer” called Barabbas.

As if!

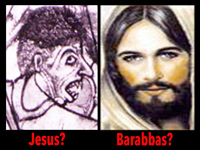

Barabbas

Mark’s use of the word “insurrectionist” is highly significant, made clearer in the original Greek:

ἦν δὲ ὁ λεγόμενος Βαραββᾶς μετὰ τῶν στασιαστῶν δεδεμένος, οἵτινες ἐν τῇ στάσει φόνον πεποιήκεισαν.

There was moreover the [one] called Barabbas with the rebels having been bound, who in the insurrection murder had committed.

Matthew, when he came to copying this passage from Mark, substituted “notorious prisoner” for insurrectionist, without further detail; Luke wrestled with Mark’s original text and subtly weakened its force: “a man who had been thrown into prison for a certain sedition started in the city, and for murder.” John substituted the innocuous “robber“.

Why on earth did the later evangelists disguise in various ways Mark’s original contention that Barabbas was a rebel, who had committed murder in the insurrection? Because it was an unwelcome indication of when Mark had authored his story: the insurrection was the great revolt otherwise known as the War of the Jews, which ended with the calamity in AD 70!

Matthew’s Mighty Makeover

Matthew, in constructing his own gospel, copied and revised Mark’s text in myriad ways. “Difficulties” in Mark’s story line were smoothed away; much of the narration was made into direct speech from the mouth of Jesus; unnamed characters were given names; emphasis was added, often by repetition, and theological points were clarified or redirected. The trial of Jesus was no exception.

Where Mark had used the voice of a storyteller to set the scene: “It was now two days before the Passover and the feast of Unleavened Bread.” (Mark 14.1), Matthew credited his hero with actually saying the same words (and added a reference to the crucifixion): Jesus said “You know that after two days the Passover is coming, and the Son of man will be delivered up to be crucified.” (Matthew 26.2)

Matthew named and highlighted the high priest and his pivotal role:

“Then the chief priests and the elders of the people gathered in the palace of the high priest who was called Caiaphas and took counsel together in order to arrest Jesus by stealth and kill him. But they said, ‘Not during the feast, lest there be a tumult among the people’ … Then those who had seized Jesus led him to Caiaphas the high priest where the scribes and the elders had gathered.”

– Matthew 26.3,57

Mark had made a mess of the testimony of the false witnesses, saying that their testimony did not agree but then providing an example where some did agree, yet adding that the testimony did not agree “even so”!

“For many bore false witness against him, and their witness did not agree. And some stood up and bore false witness against him, saying, ‘We heard him say, I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and in three days I will build another, not made with hands.’ “Yet not even so did their testimony agree.” – Mark 14.56-59

Matthew refined Mark’s clumsy text by conceding that the false witnesses eventually agreed:

“Many false witnesses came forward. At last two came forward and said, ‘This fellow said, I am able to destroy the temple of God, and to build it in three days.‘ “

– Matthew 26.60-61

Q and A with the high priest

Following closely Mark’s text the author of Matthew nonetheless made some significant changes in the “grilling” by the high priest. The first two questions were identical (“Have you no answer to make? What is it that these men testify against you?“) but with the third and most crucial question the formula changes to something more instantly familiar to Christians. Instead of copying Mark’s unusual “Son of the Blessed” – a phrase found nowhere else in the Bible and original to Mark – Matthew substitutes the familiar “Son of God”. Yet the phrase is an anachronism: the Jews never used the term as the later Christians did.

The question was given solemn emphasis and the reply from Jesus was the same as used later in his response to Pilate.

“I adjure you by the living God, tell us if you are the Christ, the Son of God.”

Jesus said to him, “You have said so.“

– Matthew 26.63-4

To emphasise that Jesus had confessed to the charge is blasphemy Matthew repeated the word:

“He has uttered blasphemy. Why do we still need witnesses? You have now heard his blasphemy. What is your judgment?”

They answered, “He deserves death.”

– Matthew 26.65

Matthew also attempted a clarification of the stranded word “Prophesy!” found in Mark’s text. Jesus was taunted to name those who struck him. To damn the Jewish priesthood further the guards from Mark’s script were eliminated. Those who struck Jesus were all members of the council!

Before Pilate – Matthew dreams up a dream!

Matthew made clear that the priests delivered Jesus to Pilate expressly to have him “put to death” (27.1). It was now Pilate himself, rather than the narrator, who stated that the charges made by the priests were “many” but again, none of these charges were revealed. Only the evasive admission from Jesus that he was the king of the Jews – “You have said so” – stands. Matthew’s governor didn’t just “wonder” – he “wondered greatly“, whatever that meant.

The wholly unrealistic notion that a Roman military governor would capitulate to a noisy crowd on the doorstep of his own headquarters was retained in Matthew’s text. But Matthew contributed a little extra colour exclusively his own: Pilate’s wife had an unsettling “dream” about Jesus! This bizarre claim – how on earth could the author of Matthew have known this? – served the purpose of “rationalizing” the odd behaviour of a Roman officer: he had been influenced by his wife’s bad dream!

“Besides, while he was sitting on the judgment seat, his wife sent word to him,

“Have nothing to do with that righteous man, for I have suffered much over him today in a dream.“

– Matthew 27.19

To emphasis his point, Matthew had Pilate, before the crowd, “wash his hands.” Not only was the Roman distanced from a sentence he did not himself agree with, the Jews damned themselves by vocalizing their acceptance of collective guilt!

“So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying,

“I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.

And all the people answered, ‘His blood be on us and on our children!’ “

– Matthew 27.24-25

Lucid Luke revamps the entire story

The more polished writer of Luke’s gospel regurgitate, reorganized and embellished Mark’s simple tale to produce a trial scene of around 900 words, three times the length of the original. It is a masterful cut and shunt of his less sophisticated source material – the texts of Mark and Matthew, and Peter.

Luke’s version of the trials has several major revisions:

1. The ridiculous night trial was dropped completely. Only “When day came” was Jesus brought before the Sanhedrin.

2. All references to the nonsense of “false witnesses” were dropped.

3. The lampooning of Jesus, with blindfold, smacking, and taunts of “Prophesy! Who is it that struck you?” is moved by Luke from post-trial to pre-trial! The jibes and “many other insults” come from guards holding Jesus at the high priest’s house.

4. The high priest is unnamed and his role is not highlighted. Rather, the “priests, elders and scribes” act and speak in unison. Collectively they chorus their questions: “If you are the Messiah, tell us.”; “Are you, then, the Son of God?“; “What further testimony do we need? We have heard it ourselves from his own lips!“

5. This groupthink continues when the assembly collectively bring Jesus before Pilate. Luke has them list the various charges that had been only alluded to in Mark and Matthew: “perverting our nation“; “forbidding us to pay taxes to the emperor“; “saying that he himself is the messiah, a king.”

6. Pilate in Luke’s edit neither “wonders” nor “wonders greatly”, nor does he “perceive envy” in the priests. Instead, he immediately finds Jesus innocent of all charges: “I find no basis for an accusation against this man.” (23.4)

7. Logic would suggest that Pilate should have released Jesus at this point. But apparently the “chief priests and the crowds” were insistent and just happen to mention that Jesus was from Galilee. And here, in his most novel innovation, Luke introduced yet another “trial”, this one before Herod Antipas, who just happened to be in town! For no obvious reason, Pilate sends Jesus across to Herod for a mind-numbing interrogation:

“He questioned him at some length, but Jesus gave him no answer.” – Luke 23.9

Herod, it seems, had hoped to be entertained by Jesus with a miracle (How did Luke know that?) but the wonder-worker said and did nothing.

8. The notion that Herod Antipas (the killer of John the baptist) also executed Jesus is a variant of the story found in the gospel of Peter. Clearly, the author of Luke worked this material into his own revision. As a result, a second “mocking of Jesus” appears at this point: in Luke, the jibes take place before Herod and his guards and not in the praetorium before a battalion of Roman troops, as in the gospels of Mark and Matthew!

“Even Herod with his soldiers treated him with contempt and mocked him; then he put an elegant robe on him, and sent him back to Pilate.”

– Luke 23.11

What on earth has been achieved by this fictitious traipse across town? Luke provides a curious answer: “That same day Herod and Pilate became friends with each other; before this they had been enemies.” (Luke 23.12) This odd comment appears to have been distilled from the gospel of Peter, in which Antipas played a more significant role.

9. According to Luke, Pilate now called together “the chief priests, the leaders, and the people.” How long did that take? What time did they assemble? Bear in mind that (according to Mark) Jesus had to be up on his cross by 9 am ! Pilate announced to the assembled multitude that both he and Herod had found Jesus not guilty of any charge and that he would be flogged and released.

10. Luke dropped all reference to a ridiculous “custom of releasing one prisoner before the feast” (Mark 15.6; Matthew 27.15). However Luke continued with the no less ridiculous fiction of having the Roman governor eventually accede to the mob demand to set free a murderer! Three times he repeats his verdict but “their voices prevailed.”

What nonsense!

The Trial – John’s final edit

The posse of fraudsters who wrote the gospel of John may have been the last to work on the inheritance from Mark but their handiwork surpassed all that had gone before. The trial sequence in John is around 1400 words – more than four times the length of the original. But John’s gospel, read in isolation, does not make much sense. Unlike the gospels of Matthew and Luke, intended by their original authors to displace the competition, John was authored by a church that had come to recognize the usefulness of alternative visions of the truth, and John was clearly designed to augment, not replace, the earlier gospels.

Consider what is NOT to be found in the gospel of John:

There is no night-time convening of the whole Sanhedrin as found in the gospels of Mark and Matthew, and no morning convening of the Jewish council either, as claimed in all three other gospels. There is no reference to false witnesses, no searching questions about who Jesus claimed to be, no cries of “blasphemy”, no tearing of garments, no verdict of “deserving death.”

Having jettisoned all this, what John does provide are some novel story elements and a lot more dialogue from the mouth of Jesus.

Two High Priests – or clumsy editing??

The authors of John inherited a situation in which Mark had not named the dastardly high priest who denounced Jesus for blasphemy; and nor had Luke named the high priest anywhere in the entire arrest and trial sequence. However John appears to have worked from Matthew’s story that gave the name Caiaphas as high priest and so the writers of John emphasised this claim:

“Caiaphas, who was high priest that year said to them, ‘You know nothing at all’ …”

“Being high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus was about to die for the nation …” – John 11.49,51

The references to “that year” are bizarre considering that Caiaphas was high priest for eighteen years! But what year was that year? If it was the year of the trial and crucifixion, then in Acts “Luke” had written that the same council which had crucified Jesus and now questioned Peter and John, was led by a high priest named Annas:

“The next day their rulers, elders, and scribes assembled in Jerusalem, with Annas the high priest, Caiaphas, John, and Alexander, and all who were of the high-priestly family.” – Luke 4.6

Luke’s comment followed closely his source – Josephus: “Now the report goes that this eldest Ananus proved a most fortunate man; for he had five sons who had all performed the office of a high priest to God, and who had himself enjoyed that dignity a long time formerly, which had never happened to any other of our high priests.” (Antiquities 20.9.1). Josephus does not say Caiaphas was a son-in-law to Annas (aka Ananus in Josephus) but John does. We also learn from Josephus that Annas had been appointed by Quirinius, the Roman Legate of Syria, in 6 AD (Ant. 18.2.1) and had been removed from office by Valerius Gratus, the Roman Prefect of Judea, in 15 AD – at least fifteen years before any supposed crucifixion!

Aware that Luke had favoured Annas as the purported high priest around the time of the trial while Matthew had opted for Caiaphas, the authors of John “harmonised” the conflicting claims with an unprecedented “two high priests scenario”, maintaining that both Annas and Caiaphas were high priest simultaneously although no rabbinical or historical source endorses such an idea.

Now an odd “time marker” also found in Luke is in his introduction of John the Baptist, where Luke writes: “In the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius … during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas” (Luke 3.1,2).

Are we really to believe that Annas and Caiaphas shared the high priesthood both in the fifteenth year of Tiberius and again in the year of the trial and crucifixion (arguably the eighteenth year of Tiberius)? The “time marker” comment is doubly curious because Luke does not repeat this claim of two high priests anywhere else and certainly not in connection with the trial of Jesus. In fact, Luke refers only to a single unnamed high priest during the arrest scene and on numerous occasions throughout his work:

” … one of them struck the slave of the high priest” (22.50) [εἷς τις ἐξ αὐτῶν τοῦ ἀρχιερέως τὸν δοῦλον] …

” … bringing him into the high priest’s house” (22.54) [τὴν οἰκίαν τοῦ ἀρχιερέως·]

Luke referred to a singular high priest at key moments in Acts (4.17; 7.1; 9.1; 22.5; 23.4), where an informed writer might have given the high priest’s name (or names) – when the apostles were arrested, for example, or when Saul/Paul was given his arrest warrant for Damascus – yet Luke cited no name. Three other high priests were appointed and dismissed after Annas was deposed– Ismael, Eleazar, and Simon – before Caiaphas was appointed high priest in 18 AD (Ant. 18.2.2). Caiaphas held the position until being removed by Vitellius in 36 AD.

So how viable is the claim for two high priests? The tenure of the two named high priests – Annas and Caiaphas never overlapped – it is a gospel fiction. The apologetic that Annas remained high priest “in Jewish eyes” is a nonsense. The high priesthood was controlled by the Romans after the province of Judea was created and the Romans both appointed and removed Annas and other high priests as they saw fit.

A pretrial?

Reconciling the contradictory claims of Matthew and Luke, the authors of John introduced yet another “trial”, a novel pretrial hearing before Annas, held at night, and in the high priest’s house. Read casually, the reader might think that Annas is identified only as the “father-in-law” to the high priest Caiaphas but in fact both men are described as high priest. John manages to emphasize that Caiaphas is high priest and yet simultaneously endorse a “two high priests” scenario!

In a radical departure from the earlier gospels, John has Annas question Jesus “about his disciples and about his teaching“, matters not touched on in any earlier version of a trial. Jesus responds with a remarkably long answer for a man otherwise taciturn at his trial!

“First they took him to Annas who was the father-in-law of Caiaphas, the high priest that year. …

Then the high priest questioned Jesus about his disciples and about his teaching. Jesus answered, ‘I have spoken openly to the world; I have always taught in synagogues and in the temple, where all the Jews come together. I have said nothing in secret.

Why do you ask me? Ask those who heard what I said to them; they know what I said …Then Annas sent him bound to Caiaphas the high priest.“

– John 18.13,19-24

No judgement was given by Annas. The key phrase here is the insistence by Jesus that he said nothing in secret, a clear put-down of Gnostic claims to a “secret wisdom” passed down to them from the master. The riposte to “ask witnesses” clearly works well with the original story element of “false witnesses” found in Mark.

2. The pretrial continues. Jesus is struck (as in Luke) but the guard now speaks – “Is that how you answer the high priest?” This elicits a non sequitur response from Jesus: “If I have spoken wrongly, testify to the wrong. But if I have spoken rightly, why do you strike me?” (18.23). The guard, surely, struck Jesus for his disrespectful manner towards the high priest, not for what he said.

After the questioning by Annas, Jesus is despatched to the other high priest, Caiaphas but, bizarrely, nothing is reported of any action or interrogation by Caiaphas – because, of course, it relies on the other gospels to “fill in the gap”!

John had, in fact, already featured a meeting of the Jewish council – and a meeting dominated by Caiaphas – earlier in his story, it was no longer part of the trial sequence.

Gospel of John:

The “Lazarus meeting” of the Jewish council – and Christian prophecy from a Jewish High Priest! Wow!

Whereas in Mark the “chief priests and the scribes” had resolved to destroy Jesus following his outburst in the temple (Mark 11.18), the authors of John made major changes to the chronology and the “cleansing of the temple” was shifted from the end to the beginning of Jesus’s ministry (John 2.14-16).

In John’s revised chronology, the climax of the story was the raising of Lazarus. This became the catalyst for the “the plot to kill Jesus” and an all-important meeting of the council. This meeting was held before Jesus stayed at a place called Ephraim, before his anointing at Bethany, and before his triumphal entry into Jerusalem.

Theological licence (and hindsight!) allowed the authors of John to use the Jewish high priest (“not on his own authority” so perhaps inspired by the holy spirit?) to prophesy that the death of Jesus would save the world!

How wonderfully convenient!

“So the chief priests and the Pharisees called a meeting of the council, and said, ‘What are we to do? This man is performing many signs. If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and destroy both our holy place and our nation.’ But one of them, Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, said to them, ‘You know nothing at all! You do not understand that it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.’

He did not say on his own authority; but being High Priest that year he prophesied that Jesus would die for the nation, and not for that nation only, but also that he would gather together in one the children of God who were scattered abroad. Then, from that day on, they plotted to put Him to death … Now the chief priests and the Pharisees had given orders that anyone who knew where Jesus was should let them know, so that they might arrest him.”

– John 11.47-57

3. Instead, “early in the morning” unnamed Jews deliver Jesus to Pilate and John adds an original comment that the Jews “did not enter the headquarters” in order to avoid defilement at Passover. Thus John establishes that the exchanges between the Roman governor and the assembled Jews takes place in a public space where, of course, “the Jews” can shout their final verdict.

Initially Pilate tells the Jews to deal with the matter themselves but “the Jews”, speaking as a chorus, argue they haven’t the authority to execute anyone. Clearly, the verdict was already in. It was, says John, a matter of “fulfilling” Jesus’ words!

Thus it is that in John’s gospel Pilate questions Jesus inside his headquarters without other Jews present (so how does “John” know what was said?).

In any event, the exchanges are pure theatre and are well-known for that reason. Pilate is ignorant of the charges against Jesus in verse 18.29 but at verse 18.33 he asks the key question: “Are you the King of the Jews?” Ironically, even Jesus responds with “Do you ask this on your own, or did others tell you about me?” – a question the reader might be asking himself!

Notice the hostility that Jesus professes towards “the Jews”, as if he and his followers were not Jews:

Pilate: “I am not a Jew, am I? Your own nation and the chief priests have handed you over to me. What have you done?“

Jesus: “My kingdom is not from this world.

If my kingdom were from this world, my followers would be fighting to keep me from being handed over to the Jews.

But as it is, my kingdom is not from here.”

Pilate: “So you are a king?“

Jesus: “You say that I am a king.

For this I was born, and for this I came into the world, to testify to the truth.

Everyone who belongs to the truth listens to my voice.”

Pilate: “What is truth?“– John 18.35-38

4. After Jesus has this private audience with Pilate, John has Pilate declare Jesus’ innocence to the Jews outside. Even so, Pilate has Jesus flogged anyway, for many victims a death sentence in itself. Roman soldiers lampoon the so-called king with a crown of thorns and a purple robe. At that point, logic suggests that Jesus should have been released. Instead, Pilate presents the scourged Jesus to the mob “to let them know” Jesus was innocent (“I find no case against him” he says twice).

Rather than invoking sympathy from the crowd however, this provokes the chief priests into cries for crucifixion. A shout from the mob (“Death for the man who has claimed to be the Son of God“) replaces the key question asked by the high priest in Mark’s original text, along with the “claim” made by Jesus, the pithy “I am” response.

Evidently frightened by the “Son of God” disclosure, the governor re-enters the praetorium (with Jesus) to ask his prisoner “Where are you from?” Jesus does not answer that question but instead speaks of “power given from above.” The enigmatic comment convinces Pilate to release Jesus (but surely he had made that decision already?).

But the Jews outside the praetorium were having none of that – of all things, threatening Pilate with the displeasure of the emperor!

“If you release this man, you are no friend of the emperor. Everyone who claims to be a king sets himself against the emperor.” – John 19.12

A Jewish mob threatens a Roman governor with the emperor? Dream on.

Only now, after the trial has been held and the outcome has been determined by “the Jews” does Pilate sit on the Judgement seat and “handed him over to them to be crucified.”

Beyond any shadow of a doubt, Rome is absolved from the murder of Jesus and “the Jews” are utterly condemned.

But it isn’t true.

It isn’t history.

But it certainly is astounding rubbish from the new Testament.

The SIX trials of Jesus?

1. Night “trial” by the Sanhedrin (Mark)

2. Morning “trial” by the Sanhedrin (Mark, Matthew, Luke)

3. “Trial” by Pilate (Mark, Matthew, Luke, John)

4. Night “trial” by Annas (John)

5. “Trial” by Herod Antipas (Luke)

6. Second “trial” by Pilate, after Jesus was sent back by Herod (Luke)

All between nightfall and noon the following day!

To add dramatic tension, the trial sequence was interwoven with a different sort of trial, that of Peter’s “denial of Jesus” and also with the farcical Barabbas “Passover pardon” episode.

More theatre.

Mark’s trials of Jesus – 360 words

Trial by the Jews

And they led Jesus to the high priest; and all the chief priests and the elders and the scribes were assembled. Now the chief priests and the whole council sought testimony against Jesus to put him to death; but they found none. For many bore false witness against him, and their witness did not agree. And some stood up and bore false witness against him, saying, “We heard him say, ‘I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and in three days I will build another, not made with hands.'” Yet not even so did their testimony agree. And the high priest stood up in the midst, and asked Jesus, “Have you no answer to make? What is it that these men testify against you?” But he was silent and made no answer. Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?” And Jesus said, “I am; and you will see the Son of man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.” And the high priest tore his garments, and said, “Why do we still need witnesses? You have heard his blasphemy. What is your decision?” And they all condemned him as deserving death. And some began to spit on him, and to cover his face, and to strike him, saying to him, “Prophesy!” And the guards received him with blows.

Trial by the Romans

And as soon as it was morning the chief priests, with the elders and scribes, and the whole council held a consultation; and they bound Jesus and led him away and delivered him to Pilate. And Pilate asked him, “Are you the King of the Jews?” And he answered him, “You have said so.” And the chief priests accused him of many things. And Pilate again asked him, “Have you no answer to make? See how many charges they bring against you.” But Jesus made no further answer, so that Pilate wondered. For he perceived that it was out of envy that the chief priests had delivered him up. Wishing to satisfy the crowd, Pilate released for them Barabbas; and having scourged Jesus, he delivered him to be crucified.

A Roman custom?

“Now at the feast he used to release for them one prisoner for whom they asked.” – Mark 15.6

A Jewish custom?

“But you have a custom that I release someone for you at the Passover.” – John 18.39

Barabbas or Jesus –

Why was the choice between just two prisoners?

If Pilate OR the Jews “had a custom” of releasing a prisoner at the holy feast why was that choice limited to just two characters?

Perhaps the “two thieves” who were crucified with Jesus should also have been considered, not to mention the many others who would have been in the Roman jails at the time!

All rather contrived, don’t you think?

The KEY question

Mark

But he was silent and made no answer. Again the high priest asked him, “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed?“

And Jesus said, “I am; and you will see the Son of man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming with the clouds of heaven.”

And the high priest tore his garments, and said, “Why do we still need witnesses? You have heard his blasphemy. What is your decision?”

And they all condemned him as deserving death. And some began to spit on him, and to cover his face, and to strike him, saying to him, “Prophesy!”

And the guards received him with blows.

Matthew

But Jesus was silent. And the high priest said to him, “I adjure you by the living God, tell us if you are the Christ, the Son of God.”

Jesus said to him, “You have said so. But I tell you, hereafter you will see the Son of man seated at the right hand of Power, and coming on the clouds of heaven.”

Then the high priest tore his robes, and said, “He has uttered blasphemy. Why do we still need witnesses? You have now heard his blasphemy. What is your judgment?”

They answered, “He deserves death.” Then they spat in his face, and struck him; and some slapped him, saying, “Prophesy to us, you Christ! Who is it that struck you?”

Luke

When day came, the assembly of the elders of the people, both chief priests and scribes, gathered together, and they brought him to their council.

They said, “If you are the Messiah, tell us.“

He replied, “If I tell you, you will not believe; and if I question you, you will not answer. But from now on the Son of Man will be seated at the right hand of the power of God.”

All of them asked, “Are you, then, the Son of God?“

He said to them, “You say that I am.”

Then they said, “What further testimony do we need? We have heard it ourselves from his own lips!”

John

Pilate said to them, “Take him yourselves and crucify him; I find no case against him.”

The Jews answered him, “We have a law, and according to that law he ought to die because he has claimed to be the Son of God.“

Not only was there no such law but blasphemy required stoning not crucifixion!

Pilate

The official residence of Pilate was in Caesarea, not Jerusalem, where he almost certainly made use of Herod’s palace (and not the Antonia fortress favoured by Christians for the trial).

The Roman governor’s questioning of Jesus was at best perfunctory. From the first, his role was to declare Jesus “innocent” – even though Jesus admitted to being a “king”.

JC and the night before his passion:

Here … Here … and Here … and Here!!!

Just where did Jesus spent what remained of the night of his arrest? The gospels say nothing but the Christian mind invented a lot of possibilities, particularly because the texts are rife with contradictions.

JC was tied to this olive tree in the garden of Annas – say the Armenians at the Convent of the Olive Tree!

A prison cell at the rear of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre? Yep, that’s what Franciscans will tell you.

This ancient cistern on the Via Dolorosa was the holy prison cell say Greek Orthodox.

Not to miss out, below the 1930s Church of St. Peter in Gallicantu, not only have Roman Catholics been fortunate enough to identify the palace of Caiaphas but also the “sacred pit” where Jesus was held.

Tiberius

Year 15 – a time marker for the entire New Testament?

It is widely understood that the fifteenth year of the reign [ἡγεμονίας / government] of Tiberius was 29 AD. But that is by no means the only possibility:

AD 4: Tiberius adopted by Augustus as his successor, with both proconsular and tribunician power (15th year = AD 19)

AD 12: Tiberius celebrated a triumph in Rome and “joint government of the provinces” (15th year = AD 27)

AD 13: Tiberius made co-princeps with Augustus (15th year = AD 28)

AD 14: Death of Augustus, accession of Tiberius (15th year = AD 29)

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.