The Sepulchres of Deceit

Exploring Jerusalem's tomb town

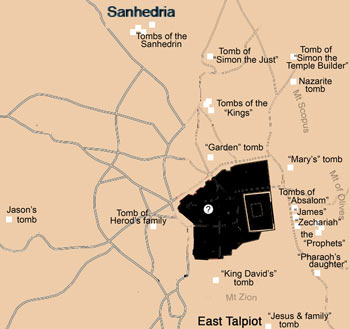

Jerusalem is encompassed by graves. The ancient cemeteries date back millennia, to the Iron Age and beyond. In this vast, circumnavigating necropolis, a number of tombs are particularly impressive, combining elements from both Greek and Egyptian design. Yet for reasons of earnest piety and venal turpitude many of the most notable tombs are misidentified. Again and again, the last resting place of some ancient plutocrat has been given surrogate fame by the attachment, “by tradition”, of the moniker of a character from Jewish myth and Christian fable.

Thus, for example, the massive, free-standing funereal monuments of the Kidron Valley, the so-called tombs of Zachariah and Absalom, are nothing of the kind, but in fact are cenotaphs dating from the 1st century BC and built for anonymous patrons. The nearby tomb of James has nothing to do with the “brother of the Lord” (“thrown from the parapet and buried on the spot“, according to Eusebius’s Church History II, 23), but is the sepulchre, clearly inscribed in Hebrew, of several members of the Hezir family.

What chance, then, that the “most sacred site in Christendom”, the so called tomb of Jesus, is anything other than a grotesque and palpable fraud?

The Tombs of Jerusalem

“Jerusalem of the period Second Temple possessed a necropolis which encompassed the city on every side. So far, hundreds of tombs have been found hewn into the rock in the form of subterranean chambers.” – Jerusalem Revealed, p17.

To the north of the Old City of Jerusalem, the so-called Tombs of the Kings contain no king and never did. At one stage a tomb here did contain the sarcophagus of “Queen Seddan”, that is, Helene of Adiabene, a 1st century queen mentioned by Josephus (Antiquities of the Jews, 20) and pious imagination has embellished this simple truth. It is, certainly, the least offensive of a panoply of holy deceits. Also north of the city is the tomb of the High Priest “Simon the Just” – except in fact it isn’t, it is the tomb of a Roman matron Julia Sabine and is inscribed as such. But devout Jews still pray here. Well, it’s the thought that counts.

To the south of the Old City, on Mount Zion, is a highly dubious “Tomb of King David” – in actual fact, an inaccessible sarcophagus much revered by pious Israelis, especially before they reclaimed the “Wailing Wall”. Mount Zion, so-called, was never part of the ancient Jebusite settlement supposedly conquered by King David. That “city” was confined to the narrow spur which runs southwest from Temple Mount. But the more westerly elevation was more impressive and Byzantine Christians identified the hill as David’s. Rock-cut tombs here were assigned to the fabled king in the 12th century and in the 14th century crusaders helped the story along by installing a massive stone sarcophagus in what then became “David’s tomb”. Another “David’s tomb” – or at least “royal tombs from the Davidic era“, are located on the “correct” easterly elevation, thus presenting the world with twice the sanctity.

In a remarkable example of divine economy, David’s giant stone coffin shares the ground floor of an unimpressive building which features the “upper room” of the first Christian Pentecost! This crusader-built chamber occupies the very spot where the Holy Ghost put some fiery spirit into the disciples. Or maybe not. The room, named the Cenacle (or Coenaculum), is directly above “David’s tomb” and within the “Mother of all the Churches“, the Dormition. The whole complex is a German Catholic theme park, established after Kaiser Wilhelm visited the city in 1898.

Perhaps even more surreal is the “Tomb of Mary” at the foot of the Mount of Olives. Although Mary died (fell asleep, dormitio) at the site of the Domition Church, the custodians of Gethsemane claimed her tomb for themselves (apparently she had once “rested” there). It should be recalled that the Blessed Virgin, unlike the rest of the human race, was without sin and therefore, at the end of her earthly life, was fast-tracked into heaven, leaving no corporeal remains to grace any tomb. Such detail could not stay pious enthusiasm for a sepulchre nor would it trouble the devout that the Queen of Heaven had another tomb, six hundred miles away at Ephesus, in Turkey, where we are assured she passed away her twilight years. Now that is impressive – no body but two tombs!

Of more practical value is the possibility (though no more than that) that members of the Jewish high council, the Sanhedrin, like the queen of Adiabene, in the 1st century AD, were buried a few miles north of the Old City in a district still named Sanhedria. In the “time of Jesus”, other members of the Judaean elite were entombed southwest of the city at Silwan, on the eastern slope of the Kidron valley. The common people, in their thousands, found their final resting place on the rocky inclines of the Mount of Olives and the low rises north of the city. No one was buried within, or even very close to the city. Herod’s family tomb – but not his own – was built to the west of the city. Tombs within the city proper are very ancient, from a time before there was a true city. In the “time of Jesus” a tomb even close to a city wall would be unthinkable – and just where were those walls?

Site of the Holy Sepulchre

The Tombs of Jerusalem

• How likely is it that a member of the Sanhedrin, sympathetic to the Jesus cause, would “just happen” to have an unused tomb – set “within a garden” no less – and closer to the heart of the city of Jerusalem than all known 1st century tombs?

• How likely that the pristine tomb of “Joseph of Arimathea” would be only a few yards away from, facing and at the same elevation as, the very spot which the Romans would choose to erect a stake of execution?

• How likely, moreover, that the man from Arimathea would get an immediate audience with and then approval from Pilate, return to the site of crucifixion, remove the body, wrap it in linen and spices, lay it in the tomb and roll the door shut, all before sundown?

The improbability of such a convenient set of circumstances is staggering, even before considering the implausibility of a character called “Joseph of Arimathea”.

City Limits

Calvary and the Holy sepulchre – inside or outside the wall?

” The city of Jerusalem was fortified with three walls, on such parts as were not encompassed with unpassable valleys; for in such places it had but one wall … The city was built upon two hills … surrounded by deep valleys, and by reason of the precipices to them belonging on both sides they are everywhere unpassable.” – Josephus, War, 5.4.1.

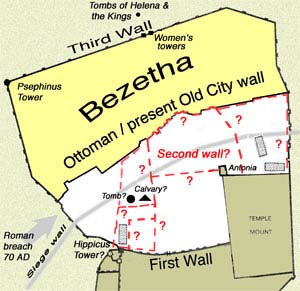

The steep valleys to the east, south and west of Jerusalem provided natural defence but at the same time inhibited the city’s expansion. Over time, therefore, the city spread progressively northward. Each of three successive north walls was built to enclose an area which was already becoming urbanised – not to protect completely vacant land, “tombs set within gardens” or places of public execution.

“As the city grew more populous,” writes Josephus, “it gradually crept beyond its old limits.” Though the precise route of each wall is uncertain, little mystery surrounds either the first north wall, built by the Hasmonean kings to protect the upper city, nor the third north wall, begun by Herod’s grandson Agrippa I in 41-43 AD and completed by the rebels during 66-70 AD. We know from Josephus that Agrippa’s wall threw a protective barrier around the “new city” of Bezetha.

“So now riches flowed in to Agrippa by his enjoyment of so large a dominion; nor did he abuse the money he had on small matters, but he began to encompass Jerusalem with such a wall, which, had it been brought to perfection, had made it impracticable for the Romans to take it by siege; but his death, which happened at Cesarea, before he had raised the walls to their due height, prevented him.” – Josephus, War 2.11.6

In preparation for his assault on the city, the Roman general Titus had “orchards, gardens and fences” cleared from beyond this third wall (War 5.3.2), which gives some idea of just how extensive was urbanisation.

Attacks upon Jerusalem, when they came, invariably came from the north, or, in the case of the assault by Titus in 70 AD, at a weakness identified in a northwestern section of the outermost wall. In the opening onslaught, the legions breached the hastily erected barrier and established a bridgehead near the tower of Psephinus. From this advanced camp the Romans were able to mount their assault on the second wall.

The route of the second north wall, however, is a matter of controversy and conjecture – not a brick has been unambiguously identified.

“Excavations … of the wall beneath the Lutheran Church of the Redeemer, ascribed since its discovery in the 1800s to the ‘Second Wall’, actually date from the days of Agrippa I, at the earliest.” – Jerusalem Revealed, p24.

In order to preserve the Christian fable the wall has to be routed around the supposed sites of Calvary and the Holy Sepulchre. Even then, the shrines are embarrassingly close to the alleged wall. If the “Hill of Calvary” had abutted the second wall one might have expected the Romans to have built a siege ramp upon it. But, in fact, the legionaries breached the second wall near the Damascus Gate and the Antonia tower.

In all likelihood, for much of its length, the second north wall lies beneath the 16th century Ottoman “Old City” wall. Even if the district immediately north of the Hippicus Tower had been outside the wall in “the time of Jesus” there is absolutely no question that the area was within the northern boundary of Aelia, the city that replaced Jerusalem, when the gospellers wrote their fable. Naturally, they make no mention of this little detail. Whether Aelia was in fact a walled city is a matter of debate. Some scholars suggest Hadrian’s city extended as far as Agrippa’s third wall and that the Damascus gate was a ceremonial arch of a central plaza.

The Walls of Jerusalem

• Would the elusive “second north wall” really have doglegged around the future site of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre?

• Would it really have contrived to leave the water reservoirs outside the city?

Somewhere in proximity to the second wall the army of Titus threw up a siege wall which circumvented the whole of Jerusalem, a feat comparable to Caesar’s classic siege of the Gauls at Alesia. Josephus reports that this barrier was built in just three days (War 5.12).

Once the Roman noose was in place, the defenders faced famine and defeat. It was a catastrophe for Judaism that seeded the ground for a heresy called Christianity.

“For the days shall come upon thee, that thine enemies shall cast a trench about thee, and compass thee round, and keep thee in on every side.” – Luke 19.43.

“Titus … was of the opinion, that if they aimed at quickness joined with security, they must build a wall round about the whole city; which was, he thought, the only way to prevent the Jews from coming out any way, and that then they would … entirely despair of saving the city.” – Josephus, War 5.12.

The Fabrication Factory –

“Joseph of Arimathea”

“The trajectory of the burial tradition sought … to move from burial by enemies to burial by friends, from inadequate and hurried burial to full, complete and even regal embalming.” – Crossan, The Historical Jesus, p393.

“Arimathea” is an unknown “city of the Jews”, and was even in the 2nd century. Matching the mystery of the town is the mystery of the man: the curiously named “Joseph of Arimathea” is unheard of anywhere in the gospel story until the closing drama of JC’s burial.

In the earliest of the narratives, the gospel of Mark, all twelve disciples were last together on the Mount of Olives when, in anticipation of his death, JC says that very night “the sheep shall be scattered” (Mark 14.27). His arrest, trial and crucifixion follow. But with the groupies dispersed who was to bury the body? Perhaps when the story was first told, with the stress upon resurrection in the Kingdom of God, such mundane detail did not matter.

However, the fate of Jesus’ corporeal remains did leave a worrying loose end. If deference were to have been paid to Jewish Law, a corpse might have been removed the same day to avoid “defiling the land” (Deuteronomy 21.23). In any event, a felon was likely to be dumped in an unmarked pit by his executioners.

Such an ignominious end to their hero was not what the story tellers had in mind.

To navigate past this difficulty, Mark introduces the weak literary device of a new character at this point, someone important enough to gain access to the Roman governor yet who has sympathies with the Jesus movement. Mark invents a curious hybrid, an “honourable member of the Jewish council, also waiting for the kingdom of God“. His model is plausibly taken from Homer’s Priam, who rescued the body of Hector for burial in a similar way.

Mark names the body snatcher “Joseph” (fatherly choice – a father was the usual candidate to bury the son) “Arimathea” (from “ari”, best and “mathai”, disciple). This Joseph, we’re told, pleads successfully with Pilate for the corpse of Jesus, buys “fine linen” to wrap it in and himself gets the body off the cross and into an unoccupied tomb. He even rolls the stone door shut. The man from Arimathea is obviously an energetic guy – strange that he never showed up earlier in the melodrama! (Mark 15.43,46).

Matthew‘s update on Mark recognizes the implausibility of a freely available tomb so he clarifies that Joseph was “rich” and that the tomb was “new” and Joseph’s “own“. Matthew also “firms up” Joseph’s religious persuasion. Remarkably, it seems this Jewish plutocrat was in fact a “Jesus’ disciple“. Pity he missed all the fun of the Ministry. (Matthew 27.57,60).

When the story falls into Luke‘s hands Luke is embarrassingly aware that Mark has previously said the Jewish Council were unanimous in their condemnation of Jesus (Mark 14.64) so he further clarifies that Joseph was “good and righteous … a dissenter” on the council. Joe is obviously the strong and silent type – he said nothing at all at JC’s trial! (Luke 23.50,53).

Spot the join

It is easy enough to see where more primitive versions of the synoptic tale were later cut and pasted with an aristocratic “retrieving the body” episode. The tale is seamless with the pericope removed.

Mark

(15.40) “There were also women looking on afar off: among whom was Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James the less and of Joses, and Salome …… [THE RETRIEVING THE BODY INCIDENT] …… And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, had bought sweet spices, that they might come and anoint him.” (16.1).Matthew

(27.55) “And many women were there beholding afar off, which followed Jesus from Galilee, ministering unto him …… [THE RETRIEVING THE BODY INCIDENT] …… And there was Mary Magdalene, and the other Mary, sitting over against the sepulchre.” (27.61).Luke

(23.49) “And all his acquaintance, and the women that followed him from Galilee, stood afar off, beholding these things …… [THE RETRIEVING THE BODY INCIDENT] …… And that day was the preparation, and the sabbath drew on. And the women also, which came with him from Galilee, followed after, and beheld the sepulchre, and how his body was laid.” (23.54,55).

Tweaking the incongruous element of a Jesus groupie on the aristocratic Sanhedrin still further (“He hid his discipleship for fear of the Jews“) and the improbability of a single-handed interment, gospeller John reprises one of his own original characters, Nicodemus. This “ruler of the Jews” helps Joe with the burial. In John‘s revised edition, the entombment acquires regal elements, involving not just the two aristocratic morticians but no less than 100 pounds of myrrh and aloes for wrappings on the body and a tomb set “within a garden“. (John 19.38,42). There is even a gardener! (John 20.15).

For all his efforts, John, unwittingly, introduces an incongruous element of his own. Joe’s supposed “secrecy” regarding his discipleship does not sit well alongside his plea to Pilate, nor with the retrieval of the body from a place of public execution, nor with the now grandly patronised interment he has given the blasphemer.

Does Joe no longer fear the Jews? And what happened to Nicodemus?

The evolution of the story did not stop there. Later narratives – not making the canon but certainly shaping Christian “tradition” – include making Joe a friend of Pilate (Gospel of Peter 2.2) and a yarn that maintains that Joe was JC’s uncle. It seems Joseph even became the guardian of Mary (move over John!), that he crossed the whole of Europe to introduce the faith to Britain (the 16th century Protestant John Foxe dreamed up that one!) and that he played a key part in the Grail saga!

Which all goes to show how very inventive is the human mind – and just how gullible.

The Fabrication Factory –

“Nicodemus”

“Nicodemus” (from the Greek, “victorious people“) is found only in the gospel of John and first turns up in chapter three as the so-called “ruler of the Jews“. It is probably John‘s embellished version of the “rich young ruler” of Mark 10, a character who wants “eternal life” and is told to sell everything “and give to the poor“. John’s more marketable version has Jesus give a different answer: “You must be born again“.

It seems that Nicodemus has been drawn to Jesus because “no man can do these miracles … except God be with him” (John 3.2). In John 3 Nicodemus is used as a foil to explain “rebirth in the spirit”, a response to the straightforward objection – no doubt met by early Christians again and again – how can an old man re-enter his mother’s womb and be born again?

What should alert us to fabrication here is that, aside from the “water-to-wine” trick at Cana in chapter two, no miracles have yet occurred. Chapter three makes clear that John the Baptist “was not yet cast into prison” (John 3.23) and according to the synoptic gospels JC’s ministry had not yet begun.

If we prefer John’s unique timeframe, JC has gathered four disciples (Andrew, Peter, Philip, Nathanael – not Andrew, Peter, James and John!) and rather vaguely, in the first of three visits to Jerusalem:

“Many believed in his name when they saw the miracles which he did, but Jesus did not commit himself unto them because he knew all men and needed not that any should testify of man, he knew what was in man.“

– John 2.24

Thus in this odd passage, it seems multiple, unstated miracles are a secret. Compounding the absurdity of it all, in John 4 our superhero is again in Cana and cures a nobleman’s son 20 miles away in Capernaum and we are told “this is the second miracle that Jesus did“! (John 4.54)

So just what was it that so impressed Nicodemus that he “came to Jesus by night” – a report from a provincial town about wine at a wedding? Fat chance.

And is it unfair to ask just who recorded the godman’s nocturnal sermon, complete with three repetitions of “Verily, verily”?

That night, in his room …

JC’s night visitor of John 3 appears to lose his “fear of the Jews” by chapter 7.

“There was a man of the Pharisees, named Nicodemus, a ruler of the Jews: The same came to Jesus by night …” – John 3.1.2.

In John 7 Nicodemus appears as the “dissenting voice of reason” within the Jewish high council. Evidently there is a debate about whether a Messiah can come from Nazareth or Bethlehem. Nicodemus warns the Jews against “pre-judging” Jesus.

“Doth our law judge any man, before it hear him, and know what he doeth?” – John 7.51.

It is, of course, divinely ordained that “the Jews” will ignore the warning – or we wouldn’t have a story!

Sources:

Robert M. Price, Jeffery Jay Lowder,The Empty Tomb: Jesus Beyond The Grave (Prometheus 2005)

Robert Gordon, Holy Land, Holy City (Paternoster, 2004)

H. J. Richards, Pilgrim to the Holy Land (McCrimmons,1985)

Shimon Gibson, Joan Taylor, Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Palestine Exploration Fund, 1994)

Joan Taylor, Christians and Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins (Clarendon, 1993)

Martin Biddle, The Tomb of Christ (Sutton, 1999)

Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land (Oxford, 1986)

Karen Armstrong, A History of Jerusalem (HarperCollins, 1997)

What’s in a name?

Tomb of Absalom. This 1st century tomb is similar to those of Petra. “Tradition” ascribes the sepulchre to the rebellious son of King David but the edifice is actually decorated with Ionic columns and a Doric frieze – designs introduced by the Greeks centuries after the fabled kingdom of David.

The Tomb of Zechariah is ascribed “by tradition” to both the Old Testament Prophet Zechariah and the father of John the Baptist! Actually, the tomb of neither.

The “Tomb of James” in fact is inscribed in Hebrew as the sepulchre of several members of the Hezir family, priests of the Temple.

The tomb of Queen Helene of Adiabene, from the “time of Jesus”. It was originally topped by three small pyramids. (Josephus, Ant. 20.4.3).

Entrance to the misnamed Tombs of the Kings.

Tomb of “Pharaoh’s daughter”. Originally the tomb sported a fetching pyramidal roof but nothing substantiates the name – beyond the pious hope that it might be the tomb of “Solomon’s Egyptian wife”. The two letters of a Hebrew inscription which remain would suggest otherwise.

Can a girl ever have too many tombs?

“Mary’s tomb”, Ephesus (Mount Koressos, Turkey). Built by 6th century Byzantines.

“Mary’s tomb”, Gethsemane, Jerusalem. Built by 12th century Crusaders.

Dormition, Mt. Zion, Jerusalem, where Mary “fell asleep”. Built by the Kaisar, early 20th century. A Benedictine franchise.

Double whammy

“King David’s” stone coffin on Mt Sion – well, somebody’s – thanks to enterprising 14th century crusaders.

Yet according to the 4th century Pilgrim of Bordeaux David’s tomb was in Bethlehem!

“From Jerusalem going to Bethlehem … On the road, on the right hand, is a tomb, in which lies Rachel, the wife of Jacob. Two miles from thence, on the left hand, is Bethlehem, where our Lord Jesus Christ was born. A basilica has been built there by the orders of Constantine.

Not far from thence is the tomb of Ezekiel, Asaph, Job, Jesse, David, and Solomon, whose names are inscribed in Hebrew letters upon the wall as you go down into the vault itself.“

Moslems continued the “Bethlehem tradition” until the 14th century.

The Cenacle. Crusaders also built the chamber above “David’s tomb” – the venue, would you believe, of the Last Supper, a post-resurrection appearance of Jesus and the apparition of the Holy Ghost at Pentecost!

Quite some value out of one slice of Catholic real estate.

You can even buy some of this holy baloney here. Modern artifacts from a fake tomb start at about $2 million.

Ever thought of getting into the religion business?

And where is ‘Arimathea’?

“He was of Arimathaea, a city of the Jews” – Luke 23.51.

“There came a rich man of Arimathaea, named Joseph, who also himself was Jesus’ disciple.” – Matthew 27.57.

A rich Jew, a member of the Jewish Council who was able to afford (and give away) a newly hewn tomb in Jerusalem could NOT have come from some bucolic hamlet, unnoted in the historical records.

“Mark’s naming him renders him more not less suspect as an historical figure.”

– Crossan, p393.

Arimathea is sometimes said to be another name for Ramathaim-Zophim in Ephraim, or Ramlah in Dan, or Ramah in Benjamin.

Why not have a guess yourself?

Highly Spiced

Can you believe Nicodemus wrapped JC in almost his own bodyweight of spices?

“Nicodemus brought a mixture of myrrh and aloes, about an hundred pound weight.”

– John 19.39.

And two days later the women who had watched the burial brought even more spices?

“And when the sabbath was past, Mary Magdalene, and Mary the mother of James, and Salome, had bought sweet spices, that they might come and anoint him.”

– Mark 16.1.

It all sounds a bit of a pickle.