Temples on the Mount - Persians and Greeks bearing gifts to Jerusalem

That elusive “Second” temple

When a real temple was built in Jerusalem in the 6th century BC, replacing whatever modest sanctum of sticks and stones had been raised by Josiah, it was built under Persian patronage. No evidence of that structure has ever been found but this so-called “Second Temple” doubtless shared design features with other Persian-sponsored sanctuaries of the same period – for example, the Temple of Eshmun at Sidon in the Lebanon, the ruins of which can still be seen. However, the port-city of Sidon, with a great fleet in the service of the Persian empire, was far richer than the modest settlement at Jerusalem and its harbour temple would certainly have been more elaborate.

In any event, the “Persian” temple in Jerusalem was destroyed during the turbulent centuries that followed and the Seleucid Greeks built a sanctuary of their own, consecrated to Zeus Olympus. This in turn was ravaged by the Maccabees who recreated a modest, rough-hewn sanctuary, the soulful structure which would be desecrated by Pompey the Great and superceded in the grand style by King Herod, in yet another incarnation of the “Second Temple.”

From Persia with love

“Our knowledge of the Temple … is derived entirely from the biblical writers, who dwelt lovingly on every remembered detail, sometimes long after the building itself had been destroyed.”

– Karen Armstrong, A History of Jerusalem, p48.

Throughout the Persian Achaemenid empire (6th – 4th centuries BC) temples were a vital part of imperial administration. Irrespective of the titular deity, an integral element of any sanctuary was its treasury, where the king’s taxes were gathered and stored alongside offerings to the gods. Much of the time, no doubt, the two revenue streams were indistinguishable. The stratagem was smart. Within the temple treasury, the king’s gold was protected by the wrath of the gods as well as temple guards.

Many cult centres esteemed both ritual cleanliness and sacrificial slaughter, conflicting goals which made essential another design feature: a constant supply of fresh water. The butchery of vast stocks of animals, with the consequential flows of blood, ash and detritus of “burnt offerings”, would have quickly fouled any sanctuary which lacked a substantial and reliable source of water.

In Jerusalem, there was an obvious choice for a holy place: above a spring already sacred. Close to the existing settlement on the Ophel ridge (the “city of David”) rose the Gihon, a perennial stream which had attracted the original Canaanite settlement to the hill above. The precious flow of water would have acquired “sacredness” from the earliest of times.

Conventional wisdom – but no evidence – places the “Second Temple” and its fabled precursor somewhere in the central plaza of Mount Moriah but it may, in fact, have been rather further south than many scholars suppose. Perhaps a hint of this is still to be found in the biblical yarn of David and Solomon. In the book of Kings the tented Ark of the Covenant had stood at Gihon for a generation when it became time to anoint Solomon:

“So Zadok the priest … caused Solomon to ride upon king David’s mule, and brought him to Gihon. And Zadok the priest took a horn of oil out of the tabernacle, and anointed Solomon. And they blew the trumpet; and all the people said, God save King Solomon.” – 1 Kings 1.38,39.

With nothing to suggest the consecration of another spot a thousand yards further to the north, the modest Persian temple, raised on an appropriate platform, may well have been built on the neck of the Ophel ridge.

But whether on the Ophel or on Mount Moriah, if a sanctuary of some description graced the environs of Jerusalem to be revered by the Jews, profaned by the Greeks and replaced by Herod the Great, surely, someone would have noticed?

Witnesses to the "Second" Temple?

“Visiting temples and sanctuaries was a key feature of pagan religious experience … Temples were places where the superhuman, the wonderful and the strange could be experienced directly.”

– K. Butcher, Roman Syria, p347.

Josephus, the 1st century Jewish historian, claims to quote from a work written by a certain Hecataeus of Abdera (a town on the coast of Thrace). This philosopher/historian lived in the 4th-3rd centuries BC and Josephus cites him as a Greek witness both to the great antiquity of the Jews (a claim made repeatedly by Josephus) and to a major city at Jerusalem.

But is this source reliable? Hecataeus suggests that the walls of Jerusalem of the 3rd century BC enclosed a city about six miles in circumference – equal, indeed, to the walls of Rome during the republican age. Yet Rome was the capital of an empire, not a small mountain kingdom. Hecataeus also opines that Jerusalem had a population of 120,000 which would have exceeded, for example, the population of 4th century Athens, again scarcely creditable. The sacred precinct described by Hecataeus, purportedly a walled-enclosure 500′ by 150′, is as bleak as a prison yard but for a high altar of rough stones and an ill-defined “large edifice” fitted out with a golden altar and a single ever-burning lamp.

Josephus also cites another witness to the second temple, from a source at least two hundred years later than Hecataeus, a so-called letter: “Concerning the Interpretation of the Law of the Jews.” This reference gives some witness to a Jewish Temple around the early 2nd century BC, from a time before Judah passed from Egyptian into Syrian control.

Purportedly written by an Aristeas and addressed to a Philocrates, the letter describes a temple structure within three walls and more than one hundred feet high.

“The Temple faces the east and its back is toward the west. The whole of the floor is paved with stones and slopes down to the appointed places, that water may be conveyed to wash away the blood from the sacrifices, for many thousand beasts are sacrificed there on the feast days.

And there is an inexhaustible supply of water, because an abundant natural spring gushes up from within the temple area. There are moreover wonderful and indescribable cisterns underground, as they pointed out to me, at a distance of five furlongs all round the site of the temple, and each of them has countless pipes so that the different streams converge together …

There are many openings for water at the base of the altar which are invisible to all except to those who are engaged in the ministration, so that all the blood of the sacrifices which is collected in great quantities is washed away in the twinkling of an eye.

Such is my opinion with regard to the character of the reservoirs and I will now show you how it was confirmed. They led me more than four furlongs outside the city and bade me peer down towards a certain spot and listen to the noise that was made by the meeting of the waters, so that the great size of the reservoirs became manifest to me, as has already been pointed out.”

Clearly, what is being described here by Aristeas neither confirms nor contradicts the earlier testimony of Hecataeus. But then we have additional references in Josephus to a rebuilding of the temple during the rule of the Antiochus III – and its transformation into a sacred grove to Zeus Olympios by his successor Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

About 300 years after “Aristeas” the Roman historian Tacitus also described the Temple of Jerusalem although in his own day the edifice was just a memory. The temple described by Tacitus, of course, was the sanctuary rebuilt by Herod the Great. Roman-style aqueducts now fed cisterns below the temple concourse but Tacitus, too, reports that the temple had within its precincts a natural spring of water fed from the interior.

“The temple resembled a citadel, and had its own walls, which were more laboriously constructed than the others. Even the colonnades with which it was surrounded formed an admirable outwork. It contained an inexhaustible spring; there were subterranean excavations in the hill, and tanks and cisterns for holding rain water. The founders of the state had foreseen that frequent wars would result from the singularity of its customs, and so had made every provision against the most protracted siege.”

– Tacitus, History, 5.12.

Changing of the guard - A Greek Polis

Shortly after the death of Alexander the Great (323 BC), an officer in his guard and one time governor of Babylon, Seleucus, retook the Mesopotamian city on behalf of Ptolemy, the general who had gained possession of Egypt. But Seleucus broke free of his erstwhile sovereign and founded a dynasty of his own. It would grow into an empire stretching from the Mediterranean to India. Under Antiochus III (222-188) – Antiochus the Great – the Seleucid kingdom became one of the richest and most formidable empires in the world.

In 198 BC, at the Battle of Panium, Antiochus finally defeated the forces of Ptolemy V and added southern Syria and Palestine to his realm. In the struggle which had raged between the Ptolemies of Egypt and the Seleucids of Syria the city of Jerusalem had changed hands six times. At length, the Jews assisted the army of Antiochus in overwhelming the Egyptian garrison within the city. In return – or so says Josephus in evidence which cannot be trusted – the great king lavished benefits on the Jews, including reconstruction of the temple.

” I would also have the work about the temple finished, and the cloisters, and if there be any thing else that ought to be rebuilt. And for the materials of wood, let it be brought them out of Judea itself and out of the other countries, and out of Libanus tax free; and the same I would have observed as to those other materials which will be necessary, in order to render the temple more glorious.”

– Edict of Antiochus, cited by Josephus, Antiquities 12.3.3

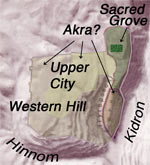

If not quite the hero of Judaism that Josephus relates, it would appear that Antiochus exercised a tolerance of the Jewish religion. Nonetheless, under the Seleucid regime the Hellenization of the province and of Jerusalem in particular – which had began during the reign of Ptolemy II (282-246 BC) – accelerated. A “modern” city – Antioch in Judaea – now superceded the Iron Age hill fort of the Jews. The focus of the town shifted to the western side of the Tyropoeon valley where a regular grid of streets was set out in a “planned” fashion, with a central agora (market place), gymnasium and a fortress – the Akra.

During this period of Syrian rule wealthy Jews received a Greek education and many took Greek names. Even the hero of Jewish expansionism in the 1st century BC, Jonathan, took the name Alexander Jannaeus upon becoming king. Laments the first book of Maccabees:

“Wicked men of Israel … built a place of exercise at Jerusalem according to the custom of the heathen, removed their marks of circumcision and repudiated the holy covenant.”

– 1 Maccabees, 1.11-15.

Such a shame. Fancy preferring a work-out at the gym to genital mutilation?

Changing of the guard - A Greek Polis

But Seleucid success brought the empire into conflict with an expansionist Rome and a fateful defeat at Magnesia in 189 BC. Asia Minor was lost and this reversal in turn encouraged rebellion in subject provinces and continuing malicious meddling from Rome.

In 175 BC, Mithridates, a son of Antiochus the Great, assumed the Seleucid throne and took the name Antiochus IV Epiphanes (175-164 BC). His ambitions were directed towards the conquest of Egypt and initially, in the minor province of Judaea, he was content to appoint Hellenizing High Priests, first Jason, then Menalaus, rivals but both leaders in the most pro-hellene faction the Tobiads.

When Menalaus sequestered Temple treasures to meet tribute promised to the king a riot of zealots forced him out of the city. Antiochus, in Egypt with his army and thwarted by Roman threats (the famous “line in the sand” story), returned to Syria, attacking Jerusalem on the way. 2 Maccabees 5 reports savage reprisals for the revolt – apparently the Lord allowed the massacre because he was temporarily “peeved with the Jews”!

“There was a massacre of young and old, a killing of women and children, a slaughter of virgins and infants. In the space of three days, eighty thousand were lost, forty thousand meeting a violent death, and the same number being sold into slavery … Puffed up in spirit, Antiochus did not realize that it was because of the sins of the city’s inhabitants that the Lord was angry for a little while and hence disregarded the Holy Place.”

With the setback in Egypt, Antiochus decided on a thoroughgoing Hellenization of the provinces nearer home: Judaea and Samaria. On Mount Moriah (Temple Mount) a sacred grove to Zeus Olympios replaced the altars of Yahweh, a redesignation repeated on Mount Gerizim. These “abominations” enraged the displaced priests of Yahweh and ultimately led to another and more serious revolt.

“The king … forced the Jews to abandon the customs of their ancestors and live no longer by the laws of God; the temple in Jerusalem was profaned and dedicated to Olympian Zeus, and that on Mount Gerizim to Zeus the Hospitable …

The temple was filled with debauchery and revelling by the Gentiles, who dallied with prostitutes and had intercourse with women within the sacred precincts …

They also brought into the temple things that were forbidden, so that the altar was covered with abominable offerings prohibited by the laws.”

– 2 Maccabees 6:1-11.

One of the “abominable offerings” was sacrificial swine, regarded as particularly offensive by the Jews (because of its resemblance to human flesh, suggests Christopher Hitchens). To add insult to injury, Antiochus followed the practice of all those earlier Jewish kings and robbed God’s treasure house.

“When Antiochus, who was called Epiphanes, lay before this city, and had been guilty of many indignities against God, and our forefathers met him in arms, they then were slain in the battle, this city was plundered by our enemies, and our sanctuary made desolate for three years and six months.” – Josephus, War, 5.9.4.

Exit Seleucids – Maccabees take up residence

A Jewish Taliban

The Maccabean conflict combined resistance to “great power” imperialism with a civil war waged between Hellenizing and reactionary Jews. In 167 BC, the Parthians under Mithridates I attacked the Seleucid empire from the east. When Herat (northwest Afghanistan) fell, the empire was cut in two. Antiochus, fighting in the east, faced civil war and secession of the coastal cities of Tyre, Tripoli, Seleucia and Sidon.

At this moment of imperial crisis, a rebellion broke out in Judah led by the clan of a renegade rustic priest named Mattathias. The so-called Maccabees (aka the “Hasmonaeans” from the name of Mattathias’ grandfather, “Asmonaios”) led a guerilla war for two decades. Although lionized in the sacred history of the Jews, the importance of the Maccabean revolt can be much exaggerated. Certainly, there were initial successes for the rebels, who frustrated the first attempts by the Greeks to reimpose order. Famously, Judas Maccabeus (166-161 BC) led the insurgents into the temple precincts, “cleansed” and rededicated the altar of Yahweh, and thus bequeathed to the Jewish people the “festival of lights” or Hanukkah.

1 Maccabees records the happy day. This meagre evidence suggests that when the rebels captured the hilltop they found “defiled stones”, a “profaned altar”, and a “thicket of bushes” (1 Maccabees 4.38) – all of which they tore down. Wailing at the desecration, “blameless priests devoted to the law” tore their clothes, dusted themselves with ash and threw themselves on the ground – behaviour which doubtless brought great delight to the creator of the universe.

But for all that, a stone’s throw from all the wailing and flaying over a few holy rocks, the Greek fortress, the Akra, remained impregnable and was never taken by the insurgents. Three years after the daring sortie on Temple Mount the Greek general Baccides hunted down and killed Judas near Ramallah.

Leadership of the rebels passed to Jonathan, the brother of Judas, but for the next nine years the Maccabees were marginalized and on the defensive. The rebellion flared up again when Antiochus died suddenly in 164. A civil war within the Greek empire provided another opportunity for a Jewish revolt.

The conflict between Demetrius I Soter (162-150) and Alexander Balas, a Greek usurper backed by the Roman Senate, allowed Jonathan Maccabeus to barter his way into the high priestship and extend his nominal territory. A second phase of the protracted civil war saw Demetrius II (145-140) confronted by the son of Balas, Antiochus VI, a youth under the guardianship of the general Diodotus Tryphon. Tryphon hunted down and killed Jonathan at Beth-shean (143). The following year the general assassinated his ward Antiochus and claimed the Greek throne for himself.

Demetrius, anxious for allies in his tussle with Tryphon, turned for support to another Maccabean brother, Simon, recognizing him as high priest and granting Judaea “independence.” At this time Demetrius withdrew the garrison from the citadel in Jerusalem; the Akra itself was repurposed as royal residence for Simon.

Soon after the “settlement”, however, Demetrius was captured on the Parthian front and his brother and successor Antiochus VII withdrew the recognition of Judaean independence. The new king defeated Tryphon in 138 and Simon himself was assassinated by the (Jewish) governor of Jericho three years later.

Despite the apparent resolution of the conflict, the Seleucid empire had been so weakened by the internecine strife that an independent Judaea nonetheless emerged. Its ruthless high priest and ruler was John Hyrcanus, the son of Simon. With tacit support from Rome, Hyrcanus extended his reach into Samaria and Idumaea with a program of forced conversions. It was John’s sons Aristobulus and Alexander Jannaeus who became the first priest-kings of the Jews. Unwittingly, Rome had helped to create a monster that would cause such anguish in the centuries ahead.

Megiddo. An altar of unhewn stones.

Remarkably, God prefers this unsophisticated pile of rocks to anything involving carved marble columns or a leafy grove. According to holy writ, any stone even scratched by iron was “defiled” and unsuitable for Yahweh.

In Jerusalem the Maccabean priests “rebuilt the sanctuary and the interior of the temple” (1 Maccabees 4.48). New holy vessels and curtains followed.

Manifestly, we are not dealing here with the “Second Temple” but yet another modest re-construction of a Yahweh cult centre in the mid-2nd century BC.

Maccabees – the original "hypocrites"

The Maccabees, who raised the banner of revolt against Greek rule in the name of fidelity to their jealous tribal god, became the new royal house of Judaea and waxed fat on idolaters’ silver. The priests of Yahweh didn’t let a little thing like idolatry get in the way of collecting loot. For all the sanctimonious nonsense spoken about a prohibition on “graven images” the very coinage of the Jewish holy temple was the “Shekel of Tyre” – a Phoenician silver tetradrachm featuring the god Melkart – a local version of Hercules. The reverse side of the coin featured an Egyptian eagle!

The Shekel of Tyre – “Graven image? That’ll do nicely!”

These pagan shekels were the only acceptable currency in the Jewish temple (and hence the infamous “money changers” of the Jesus yarn). The new found wealth financed a series of wars against their neighbours. 2 Maccabees actually condemns the Jewish High Priest Jason for sending 300 silver drachms back to Tyre for a sacrifice to Hercules (2 Maccabees 4.19).

Why the blatant use of idolatrous coinage?

The “shekel” of the Phoenician port city was prized for its consistent silver content and accurate weight. It was the only acceptable payment for the temple tax from the time of Tyre’s independence in 126 BC until the first Jewish war against Rome in 66 AD.

The writer Josephus (Antiquities 1.15) manages to gloss over the embarrassment of a pagan god on Jewish sacred coinage by maintaining that Hercules had allied himself to the sons of Abraham by his wife Keturah and that the Greek hero had actually married a granddaughter of the great patriarch!

The words of Josephus thus confirm that Hercules and Abraham were cut from the same cloth, the fabric of fiction, not fact.

But then Josephus was from the priestly caste – and business is business!

*Septuagint (LXX)

The real importance of the “Aristeas” letter is not the incidental reference to the temple but its yarn regarding the fabulous origin of the Septuagint.

Josephus (Antiquities 12, 2), Eusebius (Praeparatio Evangelica, 9.38), Philo (Life of Moses) and later writers repeat Aristeas’ story of how supposedly 72 Jewish scholars (six from each of the twelve tribes of Israel), were invited to Alexandria by Ptolemy Philadelphus to translate the books of Jewish scripture into Greek, around the year 250 BC. Aristeas says he acted as the pharaoh’s emissary to the Jerusalem High Priest and had the opportunity to admire the Temple.

But there are doubts about the authenticity of this letter, its date of composition and the entire fable.

Jerome, who made his own translation of the Hebrew bible, flatly denied the story and said the translation occurred under Ptolemy Lagus (the father of Philadelphus).

And yet this Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures was seized upon as “divinely inspired” by the early Christians. They scoured its pages gleaning “prophesies” of their own godman.

The Jewish scribes, quite reasonably, argued that the translation was not reliable. Most notoriously the LXX translated Isaiah 7.14 as “a virgin shall conceive” rather than the more accurate “young woman” – which would not work nearly as well for a prophecy of Jesus’ birth!

The legend of the Septuagint was further embellished by the Church, with more numerous miraculous elements: that the scribes independently arrived at identical translations, thanks to the Holy Spirit; that a curse fell on any who altered the text, etc., etc.

Well, why waste a good yarn?

PS: WHAT Septuagint?

The only scrap of the Greek Old Testament extant is a text dated to 150 BC. This is the Ryland’s Papyrus, #458. It contains Deuteronomy chapters 23-28.

Sources:

- Robert Gordon, Holy Land, Holy City (Paternoster, 2004)

- H. J. Richards, Pilgrim to the Holy Land (McCrimmons,1985)

- S. Gibson, J. Taylor, Beneath the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Palestine Exploration Fund, 1994)

- Joan Taylor, Christians and Holy Places: The Myth of Jewish-Christian Origins (Clarendon, 1993)

- Martin Biddle, The Tomb of Christ (Sutton, 1999)

- Jerusalem Revealed (Israel Exploration Society, 1975)

- Sami Awwd, The Holy Land (Sami Awwad, 1993)

- Peter Walker, In the Steps of Jesus (Lion Hudson, 2006)

- Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land (Oxford, 1986)

- Karen Armstrong, A History of Jerusalem (HarperCollins, 1997)

Related Articles:

A 6th century temple – in Lebanon

Ruins of the Temple of Eshmun, Sidon, Lebanon – an extant example of a Persian-inspired temple of the 6th century BC.

Judah's debt to Persia

The so-called “prison of Solomon” (Zendan-i Suleiman) at Pasargad, southwest Iran.

This enigmatic structure – about the size of an Achaemenid Fire Temple – is perhaps a guide to the modest “second temple” edifice built under Persian direction in Jerusalem.

Pasargad was the imperial capital of Cyrus the Great (559-530 BC) – a hero to the Jews for sanctioning the return to Judah of the priestly elite.

“That saith of Cyrus, He is my shepherd, and shall perform all my pleasure: even saying to Jerusalem, Thou shalt be built; and to the temple, Thy foundation shall be laid.” – Isaiah 44.28.

Sealed with a kiss?

It should be noted that Cyrus did not single out the Jews for privileged treatment.

The “Cyrus cylinder” (now in the British Museum) records the release of a number of gods in effigy that had been seized by Nabonidus, the defeated king of Babylon.

Cyrus ordered all their temples be restored and freed the captive communities to return to their homelands.

Many Jews chose to stay in Persia rather than relocate to the bleak Judaean highlands. They are still there (and have no wish to be “repatriated” to Israel!).

Persian platform builders

The Achaemenids (6th-4th centuries BC) are noted for their massive stone platforms – the base upon which a palace or temple could be built.

This one at Pasargad (Tall-i Takht) is known as “Solomon’s Throne”!

Was something similar built on the Ophel ridge in Jerusalem?

Sleucus Nicator (“Victor”) (312-281 BC), erstwhile commander of Alexander’s bodyguard, who became governor of Babylon and founder of the Seleucid empire.

Five generations later Antiochus IV (175-164 BC) harried Egypt and Hellenized Judaea.

A Greek Polis

Antioch in Judaea

Jerusalem’s western hill was first occupied by Israelite refugees who fled south following the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom.

But the shanty town was abandoned after Jerusalem itself – a tiny settlement on the spur of the Ophel ridge – was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 BC. The western hill was not reoccupied until the Greeks set out a “new town” three hundred years later.

On Temple Mount the Greeks raised a temple to Jupiter and planted a sacred grove.

Location of the Greek fortress, the Akra, is uncertain but it was probably on the western hill, facing the temple of Jupiter.

Although the Maccabean priesthood rededicated the holy sanctuary in 164 BC, it would be more than twenty years before the Syrian garrison withdrew from Jerusalem.

The Jewish priests and wealthy elite followed the example of the Greeks and built their houses on the western hill. From this so-called “upper city” they could look down on the sanctuary and the “lower city”.

Bête noire of the Jews

Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

On the reverse of this coin the god Apollo sits of the navel stone (“the centre of the world”) which was to be found at the sanctuary of Delphi.

A modest urn in Jerusalem’s Church of the Holy Sepulchre is today’s “navel stone,” honouring a rival to the ancient god – an upstart called Jesus.

A new temple on the mount

15 of what were originally 104 columns of the Olympian Zeus temple in Athens.

Did the Greeks built something similar on Temple Mount?

The walls came tumbling down

Antiochus V Eupator (164-162 BC) the son of Antiochus IV, ordered the destruction of the walls which enclosed the temple:

“Judas [Maccabeus] resolved to destroy the garrison … So he made engines of war and erected bulwarks … Renegades went to Antiochus and desired that the king would not neglect them … So the king took his army and marched hastily out of Antioch … and came against Jerusalem … when the king saw how strong the place was, he gave orders to pluck down the walls to the ground.”

– Josephus, Antiquities, 12.9.

If we are to believe 1 Maccabees the high priest Alcimus, an opponent of the Maccabees, ordered the destruction of inner walls at about the same time:

“In the one hundred and fifty-third year, in the second month, Alcimus gave orders to tear down the wall of the inner court of the sanctuary.” – 1 Maccabees 9.54

The walls rebuilt?

Jonathan Maccabeus (161-143), a brother of Judas, apparently ordered the city walls rebuilt “with square stones” (Antiquities 13.2) – suggesting that the earlier structures had been crudely built with undressed stone.

“Wicked Jews” continued to cooperate with the Greek garrison in the Akra citadel. The force did not withdraw for another twenty years.

But the “order” to rebuild may not have been carried out because Josephus reports Jonathan again “took counsel” to restore the city walls and rebuild the walls about the temple at a much later date, “and to fortify the temple precincts by very high towers.” (Antiquities 13.5)

Copied sanctity?

Mount Gerizim (Shechem/Neapolis/Nablus)

Josephus reports that about the time of the accession of Alexander the Great (336 BC) a temple was built on Mt Gerizim modelled on the temple of Jerusalem.

Apparently, this was the consequence of a delinquent Yahweh priest breaking the holy taboos by marrying a Samaritan princess. The priest’s appreciative father-in-law built him his very own temple of the Lord.

That’s not quite how the Samaritans see things, and as descendants of the northern kingdom of Israel, they actually have a better claim to the holy mountain than the Judaeans.