Philippi – The first Church in Europe or an origins myth?

It is possible that a 1st century Christian apostle called Paul sailed from the port of Troas in Asia Minor and began an evangelical crusade in Europe – but extremely improbable. Not only is the purported journey unsupported by a shred of archaeological or historical evidence but the missionary’s itinerary is a curious mix of regurgitated fable and elements cribbed from secular history. The palpable literary devices used by the author of Acts of the Apostles to “move the story on” speak volumes of the symbolic, rather than historic, nature of Paul’s journey.

Messages from the spirit world?

“And a vision appeared to Paul in the night; There stood a man of Macedonia, and prayed him, saying, ‘Come over into Macedonia, and help us.’ “

– Acts 16.9.

In the story of Paul’s “mission to the gentiles” the apostle’s first landfall in Europe is the port of Neapolis (Christoupolis/ Kavala) and the nearby town of Philippi. Paul’s journey north, it seems, has been predicated by the appeal from an apparition.

One might reasonably wonder how on earth Paul had recognized that the figure in his nocturnal vision was a “man of Macedonia”? Did he, perhaps, dress differently from other Greeks, or was it simply that the spirit had introduced himself as a Macedonian? Either way, why were the spiritual needs of Macedonia so much more deserving of the apostle’s attention than the vast number of Romano-Greek cities of Roman Asia?

It was, of course, an earlier injunction from the spirit realm that determined Paul’s action:

“Now when they had gone throughout Phrygia and the region of Galatia, and were forbidden of the Holy Ghost to preach the word in Asia.”

– Acts 16.6.

The province forbidden to Paul, in fact, was one of the richest and most densely populated in the entire empire – so why the prohibition? Until its annexation in 133 BC Roman Asia had been the kingdom of Lydia – note the name. According to Herodotus the Lydians had been the first people to introduce coinage and the name of their last king, Croesus, had become synonymous with great wealth. Surely here was a wonderful opportunity to “win the Gentiles” for Christ?

The apostle himself, far from confirming that a “night vision” called him from Asia to Philippi, gives a rather more prosaic explanation for his trip north:

“Now when I went to Troas to preach the gospel of Christ and found that the Lord had opened a door for me, I still had no peace of mind, because I did not find my brother Titus there. So I said good-by to them and went on to Macedonia.”

– 2 Corinthians 2.12,13.

Another anomaly is that whereas Acts 20.6 allows a realistic crossing from Philippi (Neapolis) to Troas in five days, this earlier crossing from Troas to Neapolis (Acts 16.11) – against both the prevailing winds and currents – is achieved in a record-breaking two days! Perhaps the Holy Spirit was blowing really hard!

Curiously, a “night vision in Asia just before a crossing to Philippi” is not unique to the book of Acts. It is also to be found in Plutarch’s Life of Brutus!

Where DID they get their ideas?

A vision appeared in the night – to Brutus!

” When they were about to cross over from Asia, Brutus is said to have had a great sign… He beheld a strange and dreadful apparition…

Plucking up courage to question it, “Who art thou,” said he, “of gods or men, and what is thine errand with me?” Then the phantom answered “I am thy evil genius, Brutus, and thou shalt see me at Philippi.“

– Plutarch, Life of Brutus, 35.

Plutarch (46-c.127 AD) was a wealthy Greek, granted Roman citizenship and equestrian rank. He wrote his Parallel Lives during the reign of Trajan (early 2nd century). Hadrian appointed Plutarch procurator of Achaea (just like Gallio!).

So who DID win Asia for Christ?

Even without Paul’s evangelical zeal, Roman Asia did become the heartland of early Christianity. Here were to be found the “seven churches” to which the Revelation of St John addressed its gore-fest of the End Time.

” I am Alpha and Omega, the first and the last: and, What thou seest, write in a book, and send it unto the seven churches which are in Asia; unto Ephesus, and unto Smyrna, and unto Pergamos, and unto Thyatira, and unto Sardis, and unto Philadelphia, and unto Laodicea.”

– Revelation 1.11.

Significantly, the writer of the apocalypse betrays no knowledge of the activities of any apostle Paul or of his seminal letters. Though the author of the Revelation relishes the martyrdom of the saints, Paul’s fate does not get a mention. Aside from Paul’s sojourn in Ephesus (“two years” and a “season“, Acts 19.10,22) at the end of his third missionary journey, there is little in either Acts or the epistles to suggest that Paul had any dealings with the major Christian communities of Roman Asia.

Unconvincingly, Acts 19.10 would have us believe that the apostle’s later stay in Ephesus was so dynamic that “all they which dwelt in Asia heard the word of the Lord Jesus, both Jews and Greeks” but this sits oddly alongside Paul’s own statement that in Asia he went in fear of his life:

“For we would not, brethren, have you ignorant of our trouble which came to us in Asia, that we were pressed out of measure, above strength, insomuch that we despaired even of life.”

– 2 Corinthians 1.8.

Indeed even in Ephesus, Paul seems not to have encountered the other celebrated divine residents. Church “tradition” maintains that the apostle John arrived in Ephesus in 40 AD, together with Mary mother of Jesus, and that they had lived out their days there.

Pope Benedict made the pilgrimage to the dubious “Virgin’s house” in November, 2006.

Roman Asia

The apostle Paul was guided away from Roman Asia by the Holy Ghost. And yet, paradoxically, the most important early Christian churches emerged in this very region.

The first reliable reference to Christians – Pliny’s letter to Trajan – relates to the province of Bithynia-Pontus, the other region denied to Paul by “the Spirit.“

So who really was the apostle to the gentiles?

And Bithynia?

The first time we hear reliably of Christians in secular history – the celebrated letter of Pliny to Trajan around the year 112 AD – it is in reference to the province of Bithynia, the province directly north of Roman Asia. Pliny, the provincial governor, is concerned about an unfamiliar “contagious superstition” and reports to the emperor “ … all I could discover was, that these people were actuated by an absurd and excessive superstition … not confined to the cities only, but has spread its infection among the neighboring villages and country” (Letter 97).

Remarkably, here is another centre of early Christianity and yet Bithynia is the other province forbidden to the apostle Paul by the Holy Spirit!

“After they were come to Mysia, they assayed to go into Bithynia: but the Spirit suffered them not.“

– Acts 16.7.

One is left to wonder, Who DID so successfully evangelize these two provinces? And why does that glorious story fail to appear in Acts? Could it be that the early Christian communities owed nothing to peripatetic apostles from Judaea and that the Pauline journeys found in the book of Acts are a fable of idealized heroics?

Whistle Stop: Samothrace

Second most important sanctuary in the Greek world.

“Therefore loosing from Troas, we came with a straight course to Samothracia, and the next day to Neapolis.”

– Acts 16.11.

Although the cursory reference to Samothrace in Acts does not say that Paul made landfall on the island, local tradition certainly does (an early Christian basilica marks the very spot!). But even the cryptic reference is significant. After all, no mention is made of the islands of Imbros and Thasos which would also have been passed by any voyager. In point of fact, Samothrace had great significance for paganism and therefore became an early target for the aggressive faith of Christ.

Before Christians destroyed the temple complex at the end of the 4th century, Samothrace had been a centre of pagan pilgrimage for a thousand years. It was the spiritual heart of the northern Aegean. The majestic island rises more than 5000 feet from the sea and as early as the 8th century BC had been colonized by Greeks from Samos (hence the name Samos of Thrace or Samothrace).

On the north coast of Samothrace, at Palaeopoli (the “old city”), the colonists began the construction of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods. The queen of Egypt (and Thracian princess) Arsinoe rebuilt the sacred precinct in the early 3rd century BC. Devotees of the pre-Olympian deities were called the Cabeiri, for whom it is said the chief symbol was the erect phallus. According to Herodotus it was from Samothrace that this icon of fertility entered the art of Greece. Illustrious initiates at the shrine included King Lysander of Sparta, Philip II of Macedon, Lucius Calpurnius Piso, the father-in-law of Julius Caesar – and the Emperor Hadrian.

“From Ephesus, Hadrian set out by ship for Rhodes and the Aegean islands. Late in September 123 he stepped off at Samothrace where, ever keen to probe to the frontiers of spiritual experience, he was probably initiated into the mysteries of the Cabiri.”

– Lambert, Beloved and God, p44.

By routing Paul via Samothrace, however tangentially, the author of Acts was able to dust a little Jesus-magic on an ancient competitor. It mattered little until a Christian emperor despoiled the much-loved sanctuary – but then a thinly drawn Christian alternative was available to eclipse the fallen gods.

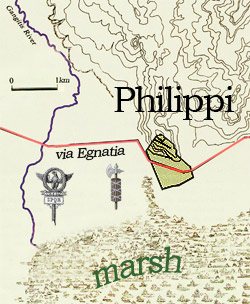

From the port of Neapolis, a half-day climb along the Via Egnatia would have brought any itinerate preacher to the walls of Philippi.

The Via Egnatia linked the Aegean and Adriatic seas and connected Rome with its eastern empire.

In the battle of Philippi, the towns of Amphipolis and Apollonia served as supply camps for the Caesareans.

Amphipolis, ignored by Paul, was a “free city” (free of imperial taxation) and the leading town of eastern Macedonia. Acts 16.12 erroneously gives that honour to Philippi.

Apollonia claims a massive standing rock overlooking the Temple of Apollo “where Paul was said to have preached”, although even Acts doesn’t support this claim.

Philippi – Paul, called by Macedonian Man, finds Woman of Asia instead!

” And on the sabbath we went out of the city by a river side, where prayer was wont to be made; and we sat down, and spake unto the women which resorted thither. And a certain woman named Lydia, a seller of purple, of the city of Thyatira, which worshipped God, heard us: whose heart the Lord opened, that she attended unto the things which were spoken of Paul.

And when she was baptized, and her household, she besought us, saying, If ye have judged me to be faithful to the Lord, come into my house, and abide there. And she constrained us.”

– Acts 16.13,15.

If Paul’s tale were history rather than fantasy it would indeed be curious that the anomalous Roman colony of Colonia Victrix Philippensium should be the first “mission” in the apostle’s evangelical campaign in Europe.

After all, Paul was supposedly drawn to Macedonia to save the souls of the locals, not Roman settlers. Compounding the anomaly, although summoned in a dream by a “Macedonian man”, Paul’s first convert is a woman from Asia, a Lydia from Lydia!

Where DID they get their ideas?

Hot Spot

Paul’s “first baptism in Europe” supposedly took place west of the city of Philippi – in precisely the same place that Octavian (Augustus) and Antony triumphed over the defenders of the Roman republic.

The river (“where prayer was wont to be made“), the marsh and the high ground determined the extent of the battlefield.

Outflanked by Antony breaching the marsh, Brutus committed suicide and Antony wrapped his body “in his best purple garment and cremated, the ashes he sent to Brutus’s mother.” (Fuller, p216).

A Jewish evangelist in town?

A difficulty in Philippi for any would-be evangelist from the Orient was that the official language of the town was Latin, not Greek, settled as it was by veterans from the legions after the great battle and, in the early 2nd century, by veterans of the Dacian wars.

“By turning out of their homes the communities in Italy which had sided with Antony, Octavian was able to grant to his soldiers their cities and their farms. To most of those who were dispossessed he made compensation by permitting them to settle in Dyrrachium, Philippi, and elsewhere.”

– Dio Cassius 51.20.

Philippi was one of only four Roman colonies in Macedonia (the others were Dion, Cassandreia and Pella), and was governed under the municipal law of Rome by two military officers, the duumviri, appointed from the capital. It’s martial character would scarcely be an encouragement to evangelism.

Religious competition in Philippi was intense. The town was particularly well-provided with pagan shrines. To the Egyptian deities introduced in the 3rd century BC – Isis, Serapis and Horus-Harpocrates – were added Artemis, Hermes, Cybele, and the “hero-horseman” from the Hellenic period; and Apollo, Silvanus, Bacchus and Jupiter from the Roman settlement.

A further difficulty for a Jewish innovator was that Philippi had no synagogue and probably few Jews. And yet in the fable of St Paul we know that the “apostle to the Gentiles” always sought out local Jews, even though, predictably, they would reject his message: Salamis (Acts 13.5), Antioch in Pisidia (13.14), Iconium (14.1), Ephesus (18.19), Berea (17.10), Athens (17.17) and Corinth (18.4). In fact, when Paul leaves Philippi we’re told that he passes straight through Amphipolis and Apollonia – major towns themselves – in order to reach Thessalonica “where was a synagogue of the Jews and Paul, as his manner was, went in unto them, and three sabbath days reasoned with them out of the scriptures” (Acts 17.1-2). This “reversion to type” illustrates how unbelievable is the Philippian episode.

In its unsatisfactory, skimpy fashion Acts indicates that, at Philippi, prayers were “wont to be made” by the river side (which could only have been the river Gangitis). It was the Jewish sabbath so one is led to believe that those at prayer that day were entreating not a river deity but the correct, Jewish god. And yet, since Yahweh wasn’t a river god, why was it necessary to gather by the river? Prayers, surely, could have been made anywhere?

The reason, of course, is that the story anticipates what is to follow: baptism. Paul finds his heroine – a gentile “worshipper of God”. Remarkably, she is already a fan of Yahweh so his task is much easier. In fact, ridiculously easy – so unlike conversion of the hard-hearted Jews! How long it took her “to attend unto the things which were spoken of Paul” we have no idea but implicitly she (and her household!) accept the new religion in a trice.

And who is this woman? Paul forsook the country of Lydia (Roman Asia) – and in northern Greece made his first convert, a woman named Lydia. And she just happened to be a native of Roman Asia! Does any of this sound entirely kosher? According to Acts, Paul and his companions “abide” in the house of this Lydia, but in Paul’s own epistle to the Philippians this first convert and early church patron gets not so much as a mention!

” I beseech Euodias, and beseech Syntyche, that they be of the same mind in the Lord. And I intreat thee also, true yokefellow, help those women which laboured with me in the gospel, with Clement also, and with other my fellow labourers, whose names are in the book of life.”

– Philippians 4.2,3.

Evidently, Lydia is not nearly so valued by Paul himself as by the author of Acts. So just who is lying here? And is there more religious symbolism in the choice of names in Paul’s own letter: Euodias (similar to Eudokia, “to seem well”) and Syntyche (meaning “common fate”)?

Where DID they get their ideas from?

St Paul and the Argonauts

“These men are the servants of the most high God, which shew unto us the way of salvation. And this did she many days. Paul, being grieved, turned and said to the spirit, I command thee in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her. And he came out the same hour.” – Acts 16.16,18.

The tale of Paul exorcising a spirit which correctly named him as a servant of the true god is both odd in itself and is blatantly a devise to move the story on to Paul’s arrest and “trial”. But the yarn was not dreamed up from thin air. Consider the parallels to that classic of Greek literature, the tale of Jason and the Argonauts!

Jason’s epic voyage was a metaphor for Greek colonization of the Black Sea coast – a “new world”. The Argonauts sailed via the sacred isle of Samothrace. Early in their voyage they encountered a soothsayer (Phineus), who has been blinded by Zeus. The god had been irritated by the seer revealing too much. The argonauts rescued the soothsayer from the Harpies and Phineus prophesied Jason’s success. The heroes sailed on to the city of the golden fleece where a woman, a priestess, proved crucial to Jason’s success.

Paul’s “epic journey” introduces Christianity to a new world (Europe). Paul also sails via Samothrace. Early in his journey he encounters a soothsayer (“a certain damsel possessed with a spirit of divination”). Paul is irritated by her revealing too much. He expels her demon spirit and rescues her from her pimps.

Paul stays in Philippi (a city famous for the local gold mines) where the help of a woman – Lydia, his first Christian convert – proves crucial to his success.

One night in jail? Welcome to Dreamland

“And when her masters saw that the hope of their gains was gone, they caught Paul and Silas, and drew them into the marketplace unto the rulers, And brought them to the magistrates, saying,

These men, being Jews, do exceedingly trouble our city, And teach customs, which are not lawful for us to receive, neither to observe, being Romans.

And the multitude rose up together against them: and the magistrates rent off their clothes, and commanded to beat them. And when they had laid many stripes upon them, they cast them into prison, charging the jailor to keep them safely.”

– Acts 16.19-23

The idea that Roman magistrates, high ranking soldiers at that, would follow the practice of Jewish high priests and tear their own clothes on hearing blasphemy, is farcical in the extreme. But then the whole “biography” of Paul in Acts is a palpable fiction. The trial in Philippi cannot itself be countenanced as an historical event because it is predicated on the unreasonable claim that the apostle and his acolytes could really have enraged the “multitude” and “troubled” the city. As ever, the Christian story-tellers love to aggrandize the comings and goings of their super heroes.

Acts reports that the magistrates accept without question the accusers’ statement and order immediate scourging. Paul and Silas (but not Timotheus and Luke?) submit to the beating, are imprisoned and only then, after a night in the stocks, claim their rights as “Roman citizens”? The author of the yarn knows full well that the story would collapse if his hero had made the claim up front.

The “Christ-like” trial, scourging and imprisonment provide the setting for a “mighty deliverance” whereby midnight prayer brings on an earthquake so localized that it merely opens doors and unfastens fetters. And unlike Peter, freed by an angel from a Jerusalem gaol, who speedily makes good his escape, Paul hangs around to baptize a convert. Such stoicism!

• How did Paul know that the gaoler had drawn his sword and was about to kill himself when he and the gaoler couldn’t see each other?

• Why would the gaoler (converted by obvious magic) have credited Paul’s prayer for the earthquake anyway – he was asleep at the time?!

• Would the manifestly unsympathetic magistrates really have reacted to a micro-tremor by releasing a couple of Jewish prisoners?

The story contrives to have Paul simultaneously in the house of the repentant gaoler (having “meat” and rejoicing) and petulantly refusing to leave the gaol until asked to leave personally by the city magistrates. Even then, Paul dallies at the house of Lydia until he’s good and ready. The motif is clear: apostolic authority is superior to civic authority. The whole tale is a pastiche of unreality.

Paul deigns to leave Philippi after “abiding certain days”. And left behind in the city – but leaving not a trace on the historical landscape – was his purported biographer, “Doctor” Luke.

Cool Hand Luke?

” If Luke travelled with Paul on the journeys covered in the ‘we passages’ he would have spent long hours talking to him on the roads and the high seas, and he should have known his character and his life story very well indeed; that would make it even more difficult to explain the contradictions between the other parts of the Acts and Paul’s letters, and the complete absence of any reference to the letters in the Acts.”

– Stourton, In the Footsteps of St Paul, p93.

Apologists sometimes suggest – without a shred of evidence – that the apostle Luke, purported author of Acts (and thus the “biographer” of Paul), settled in Philippi, thus explaining away the curious switches between “we” and “they” in the narrative of Acts. For unexplained reasons Luke was supposedly in Troas when Paul came into town.

” They passing by Mysia came down to Troas … after he had seen the vision, immediately we endeavoured to go into Macedonia … Therefore loosing from Troas, we came with a straight course to Samothracia, and the next day to Neapolis.”

– Acts 16.8,11.

Luke, it seems has joined, the great mission. But maybe not. When the “soothsayer” incident gets Paul and Silas beaten and thrown into jail, Luke (and presumably Timothy) remain fancy free. Paul and Silas soon leave town and “they”, not “we”, continue the pioneering journey.

So Luke “stays on” at Philippi?

The return to “we” narration in Acts 20/21 and again in 27/28 suggests that Luke rejoins Paul on the return leg of the apostle’s third missionary journey, having missed all of Paul’s adventures in Thessalonica, Athens and Corinth.

But just what does “Luke” have to show for his four years in Philippi? Absolutely nothing. Paul’s “one night in prison” basks in eternal fame and yet “Dr” Luke, supposedly author of both a gospel and the Acts of the Apostles, reports not a word. The fate of Luke is completely unknown (“hanged on an olive tree” and “dying naturally and unwed at 84” are both Church “traditions”).

Oh well. Perhaps Luke just put his feet up for a while and let that egocentric tentmaker from Tarsus earn his money.

Paul’s Church at Philippi?

There is neither archaeological nor literary evidence for the foundation of a Christian community at Philippi by an apostle called Paul. But there is evidence for the manufacture of martyr cult of Paul at Philippi beginning in the 4th century, that is, after the Christian religion entered the corridors of power. Funerary inscriptions indicate the presence of Christians in the city in the 3rd century but how “orthodox” they may have been is impossible to establish.

If we can believe Church “tradition” as it relates to Polycarp, a bishop at Smyrna – eighty-six years in the service of Christ and then martyrdom – in the latter half of the 2nd century the venerable bishop wrote a two-thousand word epistle to the Church of God at Philippi. Evidently, the early church here, as elsewhere, was rent by discord and factionalism. Repeatedly, Polycarp calls for “fortitude” and “endurance“. He berates “vapid discourses and sophistry of the vulgar“, warns against “love of money” and condemns “fornication, perversion and sodomy“. Clearly, the early Church had already acquired all the characteristics it would manifest in later centuries.

Aside from the sexual and financial malpractice of the Philippians, “orthodoxy” clearly had a problem with doctrinal variety – its cardinal dogmas were being challenged:

“To deny that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is to be Antichrist.

To contradict the evidence of the Cross is to be of the Devil.

And to pervert the Lord’s words is to suit our own wishes, by asserting that there are no such things as Resurrection or Judgement, is to be first-begotten of Satan.

So let us have no more of this nonsense from the gutter , and these lying doctrines, and turn again to the Word originally delivered to us.”– Epistle to the Colony of God’s Church at Philippi, 7 (Maxwell Staniforth translation, Penguin Classics)

Polycarp gives Paul a passing mention but of “Luke” he has not a word. He does, however (9.2) endorse the ridiculous “celebrity tour” of Ignatius, taking in the sights of Philippi on his way to Rome and an insistent martyrdom.

Paul writes a letter?

Supposedly, a century before Polycarp, around the year 60 AD, Paul himself wrote to the Philippians. Paul’s epistle is one of the so-called “prison letters” (together with Philemon, Colossians and Ephesians), traditionally ascribed to Paul in captivity – though without any consensus as to where or when that captivity might have been. Apparently, Paul has the services of his servant Timotheus, a truly curious “imprisonment”. Whilst the letter speaks of being a “prisoner in Jesus Christ” it also anticipates “coming shortly” to see the Philippians (1.27; 2.24), which hardly suggests impending doom:

“I trust in the Lord Jesus to send Timotheus shortly unto you … I trust in the Lord that I also myself shall come shortly.”

Does the letter really belong in the 1st rather than the 2nd century? In common with several other Pauline epistles the letter appears to be a composite of two or three original documents, itself evidence of a later hand at work. A “creedal hymn” in verses 2.6-11 (the so-called Carmen Christi) glorifying “Christ Jesus as God” and giving him “a name which is above every name” certainly indicates an inclusion from another source – and the most likely source, given the esoteric language, is early Gnosticism.

“Christ Jesus, though he was in the form of God, did not count it robbery to become equal with God … who took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men … in fashion as a man.”

The Docetists of the 2nd century would not have had much difficulty with this “appearing to be a man” formula!

The fact that the letter is addressed to “all the saints … bishops and deacons” hardly suggests the embryonic community of a new church.

The letter has no obvious motive or occasion. In part it expresses thanks to the Philippians for support, both material (“fruit“) and for the loan of Epaphroditus who “ministered” to Paul’s wants and had been sick “nigh unto death, not regarding his life, to supply your lack of service toward me” (2.30). Yet elsewhere (2 Corinthians 8.2) Paul records the “deep poverty” of the Macedonians. Apparently, the Philippians gave Paul money when no one else was forthcoming (and this support is seemingly confirmed by the reference in 2 Corinthians 11.9 to “that which was lacking to me the brethren which came from Macedonia supplied.“

But “giving and receiving” aside, Paul, here is also the target of a surprising degree of enmity from the same Philippians.

“Some indeed preach Christ even of envy and strife … Christ of contention, not sincerely, supposing to add affliction to my bonds.” – 1.15,16.

Why would Paul be facing such hostility at this early stage? In his sights, of course, are the Jews or “Judaizers” and in the epistle Paul takes the opportunity to brag of his own Jewish ancestry – “Circumcised the eighth day, of the stock of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin, an Hebrew of the Hebrews; as touching the law, a Pharisee.” Such fulsome “self-disclosure” might well betray the over-compensation of the forger as much any foil for the Jews. Paul rejects his Jewish credentials, warning of “Jewish dogs”, and calling Judaism “dung”:

“Beware of dogs, beware of evil workers, beware of the concision … But what things were gain to me … and do count them but dung.” – 3.2,8.

But why would Paul need to issue such a warning to a Latin city and to a congregation made up of non-Jews? Was it not after, rather than before, the Jewish wars that Jews were dispersed in any numbers across the eastern Mediterranean – or are we to suppose that numerous Jewish proselytizers followed Paul’s unlikely path to Philippi – all of them disdaining a hundred more accessible towns?

A Christian city

“The events recorded in the Gospels had little or no immediate or ostensible influence upon history … Historically, the Church came into existence in a world ostensibly quite unchanged by the events in which the Kingdom of God came … The Church had emerged and yet there was scarcely a ripple on the surface of the great stream of history in the Graeco-Roman world.”

– C. H. Dodd, Professor of Divinity, University of Cambridge (History and the Gospel, 1938, p102,3)

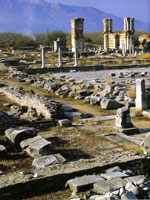

Beginning in the 4th century, and after Constantine’s seizure of power, all the large public buildings at Philippi were replaced by churches. In the centre of town stood a 2nd century AD Hellenistic heroon (hero’s shrine), built in memory of an initiate of the Samothracian mysteries. It was replaced by the earliest of several churches, an octagonal structure dedicated to St Paul. Nearby, a whole city block was taken up with the bishop’s residence, including his own winery. Another small church, dating from the late 4th century, was built within a mixed pagan/Christian graveyard to the east of the city.

In the 5th century, a large basilica was built over the proscribed pagan sanctuary on the north side of Philippi. It was brought down by an earthquake shortly after completion and was never rebuilt. In the following century, in the southern quarter, the Christians demolished the 80 metre palaestra (the wrestling/athletics court) and robbed-out the stones to build another basilica. This poorly designed structure collapsed before it could be dedicated! Four hundred years later its ruins were re-purposed as a less ambitious church, the remnants of which can be seen today.

In the Christian city, the bathhouse complexes were converted to workshops which quickly went out of use. The communal latrine adjacent to the palaestra (seating for 42!) – offensive to Christian sensibilities – disappeared under the courtyard of the basilica. The last attempt to strengthen the city walls was made by Justinian in response to attacks by the Goths. From the 7th century onward the population began to abandon the town, many for the relative safety of villages hidden in the mountains. In the later Byzantine period Philippi was simply a fortress and by the 15th century, a ruin.

An Origins Myth

The incredulous conversions made by the apostle Paul in Philippi – the Asian “Lydia” (and her household!) and his overnight gaoler (and his household!) – underscore the entirely fictional nature of the supposed establishment of a foundational church by the apostle in this most unpromising of towns.

The curious anticipations of divine word to be found in prosaic literature, the inane contrivances of plot found in the book of Acts, the palpable falsity of so-called epistles to Philippi, the martial character of this Latin city, the invisibility of the “resident evangelist” Luke – all point towards a single conclusion: Paul’s escapade and daring-do in Philippi is nothing other than pious fabrication.

That a church was eventually established in the city no later than the 4th century is not in doubt. But its existence is most certainly the result of two processes: official patronage of the Christ cult which followed the triumph of Constantine; and the ernest desire to give physical form to an heroic “origins” tale already celebrated in a religious fable.

Sources:

Edward Stourton, In the Footsteps of Saint Paul (Hodder & Stoughton, 2004)

Evangelia Kypraiou, Philippi (Hellenic Ministry of Culture,2006)

I. Touratsoglou, Macedonia (Ekdotike Athenon, 2004)

L. I Hadjifoti, St Paul, His Life and Work (Toubis, 2004)

Si Sheppard, Actium 31 BC: Downfall of Antony and Cleopatra (Osprey, 2009)

Si Sheppard, Philippi 42 BC: The death of the Roman Republic (Osprey, 2008)

Early Christian Writings (Maxwell Staniforth trans., Penguin1978)

J. Murphy-O’Connor, Paul, A Critical Life (Clarendon, 1996)

“Frontier town”

Philippi 2nd century forum with 6th century basilica beyond.

Until the annexation of Thrace by Claudius in 46 AD, Macedonia was Rome’s most easterly province in Europe and Philippi its most easterly city.

If, in the late 40s or early 50s, Paul really had been traipsing west, he might have passed units of the Moesian legions moving east, as the new province was organized!

New World Order

Victoria Augusta. This relief on a theatre pillar at Philippi commemorates the victory of Octavian and Antony in 42 BC.

Acts 16 claims that St Paul was “called to rescue Macedonians” – but then went on to establish a church in this Latin-speaking town, populated by retired Roman soldiers.

Early colonists at Philippi included troops formerly loyal to Antony who were displaced from Italy after Octavian’s victory at Actium in 31 BC.

Flying Pigs Department

“What made it possible for a wandering Jewish preacher and part-time tentmaker to turn up in a city knowing no one, and leave it with a new Christian church firmly established there?”

– Stourton, In the Footsteps of St Paul, p88.

Mystery Island

Samothrace – rising more than 5300′ from the sea. Too mountainous for cultivation, the high peaks and deep wooded valleys, often shrouded in mist, give the island an aura of “mystery and magic”.

Paul, we’re told, passed this way. If true, he was passing a pagan sanctuary second only to Eleusis in importance.

In contrast to the Mysteries of Eleusis, the rites of the Great Gods were open to all – “male and female, slave and free.“

The Great Gods

“Winged Victory of Samothrace” – ancient pre-Christian masterpiece.

This statue of the goddess Nike once graced the Sanctuary of the Great Gods.

The sacred island of Samothrace remained independent until Vespasian absorbed the island into the Roman Empire in AD 70.

Dancing Girls, Randy Gods

Samothrace was the site of important Hellenic and pre-Hellenic religious ceremonies. The primary god was the “Great Mother” Alceros Cybele, a fertility goddess, whose consort was the phallic god Kadmilos.

Paul’s water cistern “prison”

What purports to be Paul’s “prison” is actually a water cistern to the side of a temple precinct.

The extant ruins show no evidence of a highly localized “earthquake”, nor are they large enough for an “inner” (and presumably “outer” prison), stocks, doors and several prisoners – all part of the fairy tale of Acts 16. Remnants of pious frescoes from the 6th century are still visible.

In reality, in the degenerate city of the Byzantines, a suitable structure was chosen as a shrine to enthrall the gullible. The short-lived prosperity of the city in the 5th and 6th centuries was largely due the martyr cult of Paul.

Tour parties of Christian pilgrims still visit the “prison” today. Local archaeologists are reluctant to disabuse a lucrative income stream.

‘After the church was destroyed a chapel was built outside the southwest corner of the atrium; a cistern lay beneath it, which was later transformed into a cult place with frescoes, believed to have been “St Paul’s Prison”. ‘

– Evangelia Kypraiou, Philippi (Hellenic Ministry of Culture,2006) p32.

Thyatira feels the heat

“And unto the angel of the church in Thyatira write;

… because thou sufferest that woman Jezebel, which calleth herself a prophetess, to teach and to seduce my servants to commit fornication, and to eat things sacrificed unto idols …

I will cast her into a bed, and them that commit adultery with her into great tribulation … And I will kill her children with death; and all the churches shall know that I am he which searcheth the reins and hearts.”

– Revelation of St John 2:18-23.

Thyatira thanks Hadrian

An inscribed decree from a city of Asia is to be seen at Athens – the place where Paul eventually finds himself.

The inscription hails Hadrian as the “greatest of kings”, thanks Hadrian for inaugurating the Panhellenion (the “all-Greek” league) and honours Hadrian for his beneficence to the city. That city was Thyatira.

(Lane Fox, The Classical World).

Luke WHO?

It is questionable whether the author of the “genuine” Pauline epistles knew of any “biographer” named Luke.

In the entire Pauline corpus there are only three passing mentions of a Luke – and all appear in epistles deemed “inauthentic” by many scholars.

Colossians 4:14

“Luke, the beloved physician, and Demas, greet you.”

2 Timothy 4:11

“Only Luke is with me. Take Mark, and bring him with thee: for he is profitable to me for the ministry.”

Philemon 23-24

“There salute thee Epaphras, my fellow prisoner in Christ Jesus; Marcus, Aristarchus, Demas, Lucas, my fellow labourers.”

Even if these references were genuine they surely damn with faint praise the supposed evangelist. No wonder Luke’s “biography” of Paul scarcely agrees with a word of Paul’s own epistles!

The earliest evidence of the name “Luke” associated with a gospel is the Muratorian fragment, dated to about 170 AD.

Baur on “Philippians”

” In a genuine Pauline Epistle we should expect that, besides the spiritual content, one should expect some new information not derivable from other sources — about the situation and circumstances at the time, the occasion of the writing, and so many matters of interest which unmediated reality transmits of itself.

Here, however, we have poverty of thought, absence of any historical motivation, lack of coherence; we have nothing specific or concrete, nothing to give us the impression of originality, nothing but a dull and colourless reflection.”

– F. C. Baur, Paul. The Apostle of Jesus Christ, 1875.

Pagan head at Philippi defaced with Christian cross on forehead.

By the 4th century the golden age of sculpture had passed but pious vandalism was coming into its own.

Philippi – a Latin town

A traitor called “Christ”!

In 65 AD a plot to assassinate Nero led by Calpurnius Piso was betrayed by a freed slave called Milichus working in the service of a fellow conspirator, Flavius Scaevinus. Records Tacitus:

“His slave’s brain considered the rewards of treachery and conceived ideas of vast wealth … He was taken by the door keepers to Nero’s freed slave Ephaphroditus – who conducted him to Nero …Milichus was richly compensated, and adopted the Greek word for ‘Saviour’ as his name.“ – Annals 15.15.

When Nero botched his suicide two years later, it was his own former slave Ephaphroditus who completed the job. The freedman shares the name of Paul’s supposed playmate from Philippi and in his epistle to the Philippians Paul calls him a “fellow soldier“.

The same letter refers to “the palace” and closes with a curious salutation from “Caesar’s household” – often interpreted as (ludicrous) references to Christians within the praetorian guard or state officials.

But the author of the epistle may simply be trying to establish rapport with a military canton whose residents would respect such terms.

Flush toilets – NOT the Christian way

The communal latrine at Philippi was flushed clean by a continuous flow of water. The facility was regarded with shame by the Christians and was buried during the construction of the Christian basilica.

Presumably God favoured the pot and a more hazardous disposal method.

St Paul – Real or Imagined?

- A Jew called Saul? An apostle called Paul? A witness to Jesus? Or plain invention?

Up Close and Personal - A journey to Cyprus? A mission to Galatia?

Mission Impossible - Big city tour? Athens, Corinth, Ephesus?

Magical Mystery Tours – A Greek Odyssey - Voyage to Rome? A martyr’s death? “Tradition” versus truth.

Magical Mystery Tours – The Road to Rome - Epistles? Letters home? Papering over the cracks.

From our own Correspondent Part 2