Persecution – Holy Mother Church Invents Heroic Origins

"God protects us" says Church Father.

“God interposed His providence on behalf of believers, dispersing by an act of His will alone all the conspiracies formed against them; so that neither kings, nor rulers, nor the populace, might be able to rage against them beyond a certain point. A few engaged in a struggle for their religion, and these individuals who can be easily numbered, have endured death for the sake of Christianity.”

– Origen of Alexandria (c184-254) (Contra Celsus, 3.8)

Mind of a Fanatic

“There is a persecution of unrighteousness, which the impious inflict upon the church of Christ; and there is a righteous persecution, which the church of Christ inflicts on the impious … Moreover she persecutes in the spirit of love, they in the spirit of wrath.”

– St Augustine (Letter 185, 417 AD)

Psycho-Terrorism

The Roman Empire lasted more than a thousand years and persecuted Christians for fewer than twelve of them. The ‘Christian Empire’ also lasted more than a thousand years and persecuted non-Christians through all of them.

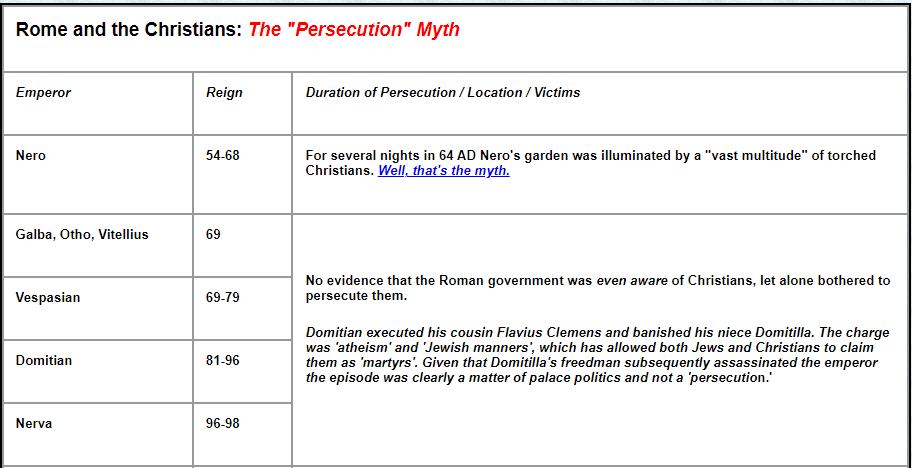

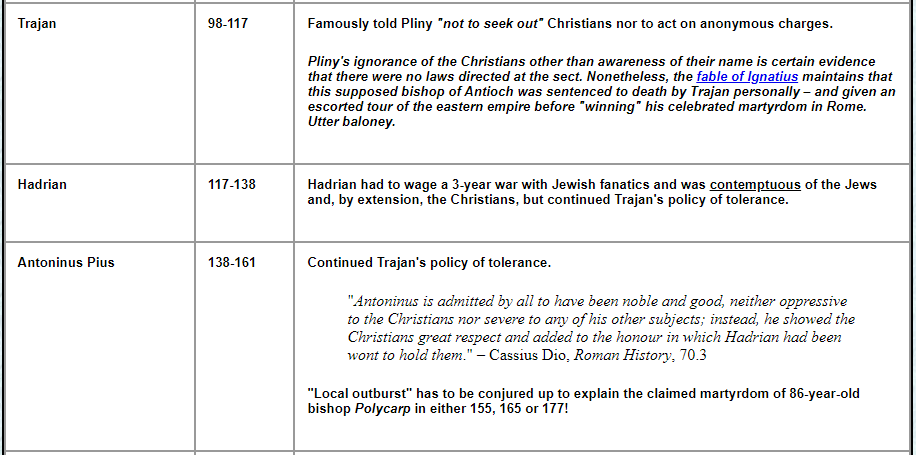

Until the early years of the 2nd century, Roman administrators were ignorant of the existence of the Christians. For a generation that followed they remained indifferent to this obscure ‘Jewish’ sect (and its many different factions) but, in time, this indifference gave way to contempt and then irritation.

The still marginal but growing numbers of Christians turned the misfortunes of the Roman world to their advantage. The radicals directed their energies towards frightened widows and abandoned children, towards the slave and criminal classes. Every defeat in battle, every pestilence and natural calamity, was seized upon as evidence of divine censure and retribution. With zeal and anticipation, the Christians predicted further ruin and desolation. Among the feckless peoples of the great cities, the fear of imminent judgement and the threat of eternal torment were spread like a contagion. Only by submission to Christ could the individual hope for salvation. “Babylon” would surely fall and most of humanity would perish.

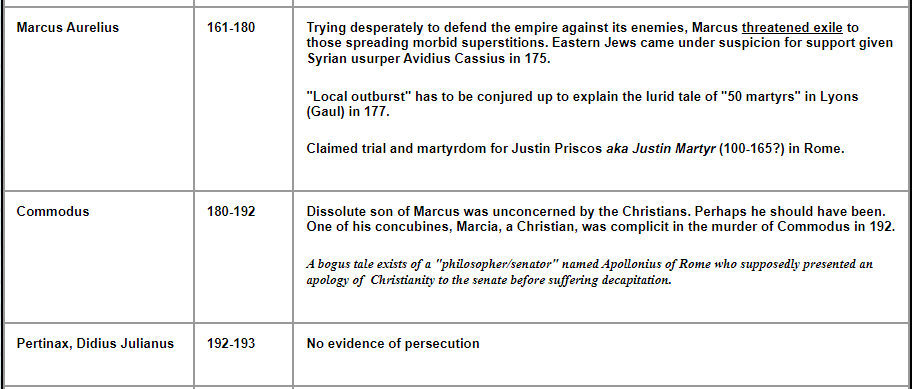

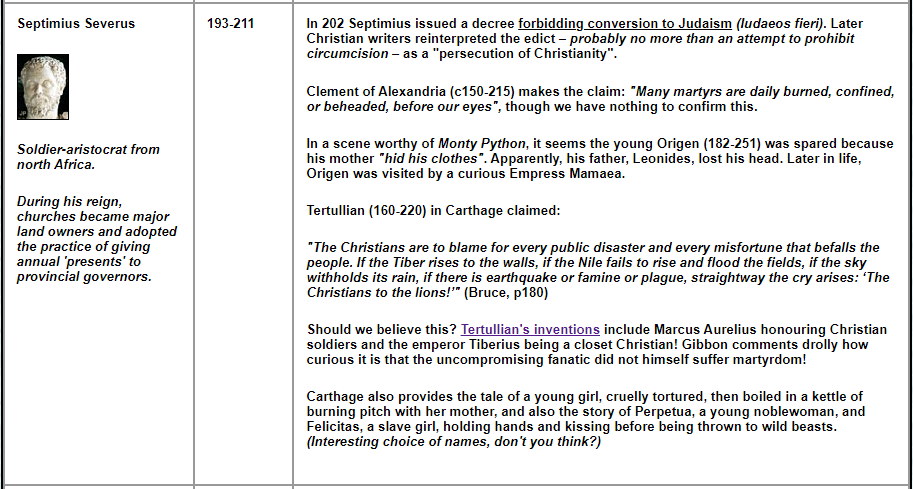

Yet it was only when the empire was itself in peril that the Roman state acted violently against the enthusiasts of Christ, and only then because the obstinate prejudices of the zealots undermined desperate measures taken to defend Roman civilization.

Bad is Good

By concerted psycho-terrorism the Christians demoralised a population immeasurably larger than their own diminutive numbers. Ultimately, the self-confidence and majestic pride of Rome, which had wrested a world from the barbarian, was sapped and eroded by the partisans of Christ. By the mid-years of the 3rd century the empire began fragmenting, with separatist regimes in Gaul and Syria, and its only recourse was to lurch into military despotism and a corporate state.

The 3rd century was an age of chronic instability for the Roman world. After the corruption introduced by the Syrian monarchs first the Praetorian Guard and then the frontier Legions intervened repeatedly in the making and breaking of emperors.

This militarisation of the state was reflected in the church itself, which, by the late 3rd century, had purged itself of independent minds and had replaced democratic elements by disciplined hierarchy. The defeated factions, like mutinous bodies of troops, seceded and continued a resistance. The main body of the church, committed to the ‘orthodoxy’ of international organisation if not yet the ‘orthodoxy’ of doctrine, confronted the Roman State as a “Republic within the Republic”, with its own treasury, laws, magistrates and command structure.

When, in the early 4th century, reluctant emperors attempted to eradicate the public menace it was too late. Though the Christians constituted perhaps five per cent of the population they were concentrated in enclaves in the key cities of the east. When the churches were closed the imperial palace at Nicomedia was twice fire bombed. When the zealots were arrested, an ambitious prince in the west, Constantine, made the fanatics of Christ the subject of his patronage and protection.

5-4-3-2-1

In 286, Diocletian promoted his trusted colleague Maximian to the rank of Augustus. Seven years later he appointed two new Caesars, Constantius, given Gaul and Britain in the west, and Galerius, assigned the Balkans in the east. The intention was to provide an imperial presence in all sectors of the empire and provide for orderly succession. On 1 May 305, Diocletian abdicated, compelling his co-Augustus Maximian to do the same. Constantius and Galerius became the new Augusti, and two new Caesars were chosen, Severus in the west and Maximinus Daia – nephew of Galerius – in the east.

Maximinus Daia (Maximin) based his court at Caesarea and ruled Egypt, Syria, and Asia Minor. Though these were among the richest provinces of the empire they also presented Maximin with the most contentious problem of Jewish and Christian radicals.

In 306 the orderly management of the empire fell apart. The sickly Constantius died. Severus became Augustus but the ambitious son of Constantius – Constantine – compelled his acceptance as Caesar from his fortress at Trier. Then another malcontent, Maxentius, the son of Maximianus, proclaimed himself Augustus in Rome.

Galerius, the senior monarch, convened a conference at Carnuntum in late 308 to resolve matters. Severus had fallen in battle against Maxentius and Galerius appointed Licinius, another army colleague, in his stead. But Licinius chose to remain with his troops in the Balkans rather than move against Maxentius in Italy.

Thus, in the years immediately before that celebrated “Battle of the Milvian Bridge”, 5 pagan princes contended for mastery of the Roman world: in the west, Constantine in Gaul, Maxentius in Italy, Licinius in the Balkans, Galerius in Nicomedia, and Maximin in Caesarea.

Galerius and Maximin, confronting a “Christian problem” demoralising their forces and causing commotion in the cities, adopted a hard line policy towards the obstinate fanatics. Licinius back-pedalled on the official policy. In the west, where factions of the church in Rome and Carthage were themselves in conflict, Maxentius adopted a policy of toleration, hoping for Christian support for his rebellion. Constantine, in pagan Gaul where no Christian problem existed, not to be outflanked, proclaimed himself “protector of the Christians.”

And then, in 311, Galerius died. Licinius and Maximin divided the east along the Bosphorus, with Maximin taking possession of the heart of the empire. His emissaries sought an alliance with Maxentius in Italy. The following year Constantine made his move and trounced Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge.

Now three princes wrestled for supremacy.

At this late hour, Maximin tried to defeat his Christian adversaries in the great eastern cities by hastily organising the disparate pagan priesthoods into a hierarchy to match the Christians. Pontiffs and Metropolitan High Priests, chosen from noble families, were granted the powers of magistrates to enforce the edicts on sacrifice. Temples were restored and invigorated ceremonials introduced. The governor of Antioch, Theotecnus of Antioch, even circulated forged “memoirs of Pontius Pilate” casting Christ in an unfavourable light.

“The zeal and rapid progress of the Christians awakened the Polytheists from their supine indifference in the cause of those deities whom custom and education had taught them to revere,” – Gibbon, Decline & Fall, 16.

Meanwhile, the wily Constantine forged an alliance with Licinius to divide the world. Meeting at Mediolanum, Constantine married his sister to his erstwhile rival and together they promulgated the so-called ‘Edict of Milan’, granting Christians (and others) freedom of religion. It was a policy designed to cause Maximin the greatest difficulty. Enraged, he forced-marched his troops across Asia Minor in the depths of winter to take Byzantium by siege.

Licinius’ counter-stroke with fresh troops routed Maximin’s exhausted troops and he fled back to Tarsus. He took ill and died – to the jubilation of the Christian bishops. Licinius’ triumph was short-lived. Having eliminated Constantine’s most implacable enemy, Constantine returned the favour by destroying Licinius’ army and executing his unloved brother-in-law. Thus did an eminently qualified ‘Christian’ monarch emerge as master of the world.

Body Count

“From the history of Eusebius it may however be collected that only nine bishops were punished with death; and we are assured, by his particular enumeration of the martyrs of Palestine, that no more than ninety two Christians were entitled to that honourable appellation …

Palestine may be considered as the sixteenth part of the Eastern empire … it is reasonable to believe that the country which gave birth to Christianity produced at least a sixteenth part of the martyrs who suffered death within the dominions of Galerius and Maximin; the whole might consequently amount to about fifteen hundred … an annual consumption of 150 martyrs.”

– Gibbon, Decline & Fall, 16.

Gibbon calculated 1500 martyrs for the whole climatic decade of persecution in the more populous east. The western provinces were little affected and such persecutions as occurred were of brief duration. In total, then, the pagan assault on the Christians, throughout a 300 year period, claimed “somewhat less than two thousand persons.”

We might set this number against any number of comparisons. Victims of the witch trials, burnings and lynchings during the period 1300-1800 are conservatively put at 35-65,000 (and many estimates are much higher). Victims of the Inquisition, though sometimes speculatively put in the millions, in any event far exceeded anything dreamed of by the cruellest of Roman emperors. Gibbon himself draws a contrast with the 100,000 Protestant Netherlanders committed to the executioner by the Catholic Charles V of Spain.

But the real comparison is between the thousand years of Greco-Roman civilisation and the fifteen centuries of darkness that were to follow …

Pay Back Time: The Christian Torture Garden

‘Wherever we look, bishops were encouraging the landed elites… to take firm and coercive action to make the peasantry Christian …

Like it or not, this is what our sources tell us over and over again. Demonstrations of the power of the Christian God meant conversion. Miracles, wonders, exorcisms, temple-torching and shrine-smashing were in themselves acts of evangelisation.”

– Richard Fletcher (The Conversion of Europe, p45)

With the triumph of Constantine the inmates came into possession of the asylum. Their insanities were to become the only acceptable world view. Demonic nonsense, dreamed up in the psychotic mind of the pious theologian, populated the natural world with monstrous phantoms and set Satan’s familiars at every cherished spring and venerable grove. Ever more lurid descriptions of Hell instilled dread and terror. Every town and hamlet was polluted by limitless malevolence – from which the only deliverance was complete submission to Holy Mother Church and her rapacious agents.

Constantine placed himself at the head of the collective of Christian fraternities, rewarded their bishops and obtained their fawning adoration. Fanaticism was now pressed into service as the propaganda of a divine monarch; zealotry was directed, not merely at the pagan and the skeptic, but also at the brethren who had failed to understand the true nature of the political revolution, had failed to adapt to servitude in the kingdom of the world and still cast their eyes, wistfully, on an anticipated kingdom of heaven.

Christian monarchs would far surpass in resolution and cruelty the mild attempts of the pagan caesars to eliminate such unacceptable thoughts:

“In the century opened by the Peace of the Church, more Christians died for their faith at the hands of fellow Christians than had died before in all the persecutions.“

– Ramsay MacMullen, Christianity and Paganism in the Fourth to Eighth Centuries, p14.

- PMichael Walsh, Roots of Christianity (Grafton, 1986)

- Arthur Ferrill, The Fall of the Roman Empire (Thames & Hudson, 1986)

- Edward Gibbon, The Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire (1799)

- Michael Grant, The Climax of Rome (Weidenfeld& Nicolson, 1996)

- Chris Scarre, Chronicle of the Roman Emperors (Thames & Hudson, 1995)

- Robert Wilken, The Christians As the Romans Saw Them (Yale UP, 1984)

- Keith Hopkins, A World Full of Gods (The Free Press, 1999)

- J. D. Randers-Pehrson, Barbarians & Romans (BCA, 1983)

- Robin Lane Fox, Pagans & Christians (Viking, 1986)

1000 Years of Carnage & Barbarity in the name of Christ

Missionaries or Murderers? – The Christianising of Europe

Constantine – Pagan Thug Makes Christian Emperor

Winter of the World – The Terrible Cost of “Christendom”

Heart of Darkness – The Criminal History of the Christian Church

Rome's War on Terror

Religious fanatics, rejecting the values of a cosmopolitan world culture and convinced that only they knew the will of God, challenged the efforts of Rome’s most capable emperors to establish consensus and unity.

The Christians stood apart, refusing military service and discouraging others; they scorned the State gods, and interpreted the misfortunes of the Empire as the prophesied prelude to the destruction of “Babylon” and the return of their Christ.

Tertullian – Hard Line Christian, Enthusiastic About Divine Retribution

Mind of a Fanatic

Shock and Awe:

“You are fond of spectacles. Expect the greatest of all spectacles, the last and eternal judgement of the universe.

How shall I admire, how laugh, how rejoice, how exult, when I behold so many proud monarchs, and fancied gods, groaning in the lowest abyss of darkness; so many magistrates who persecuted the name of the Lord, liquefying in fiercer fires than they ever kindled against the Christians.”

– Tertullian, salivating at the thought of Armageddon. (Gibbon, Decline & Fall, 15)

Mind of a Fanatic

Sound familiar?

According to the precepts of 2nd century Christianity, those who died a martyr’s death (“the baptism of blood”) went immediately to paradise and there awaited reunion with their bodies at the resurrection of the dead.

Church Father Tertullian (160-220) introduced the novel idea that a martyr’s day of death was his “birthday.“

Decius - 'The first Persecutor'

“The persecution initiated by Decius was itself the first general attack against Christianity ever undertaken by the Roman government as a matter of deliberate policy…

It is essential to recognize that no emperor before Decius, in the mid-3rd century, mounted a centrally organized campaign against Christianity, and that until that time the issue was never particularly important in the mind of any Roman emperor.”

– T. Cornell, J. Matthews, Atlas of the Roman World, p177.

Oath of allegiance

During the rule of Decius, all citizens of the empire (not just Christians) were required to obtain a libellus, an ‘oath of allegiance’.

With a suitable payment, wealthy Christians could buy this ‘Get out of jail’ card without making the oath.

Diocletian and Maximian

Personal?

“On account of Decius’ hatred of Philip he commenced a persecution of the churches.”

– Eusebius, EH, 6.39.

Christian violence

“Any attempt to draw a scale of religious violence in this period must place the violence of Christians towards each other at the top.“

– Peter Brown, ‘Christianisation and Religious Conflict’, Cambridge Ancient History, p647.

Now, was he a Christian?

Executing pagans

“The next step was to strip the other enemies of the true religion of all their honours, and to execute all Maximin’s sympathizers especially those in government circles who held office under him, and as a sop to him had poured violent and irresponsible abuse on our teachings.“

– Eusebius, EH, 9.3

If You Can't Beat Them, Join Them

“The supernatural powers assumed by the church inspired at the same time terror and emulation … The Pagans … mutually concurred in restoring and establishing the reign of superstition.”

– Gibbon (Decline and Fall)

Medieval churchmen knew torture in “exquisite detail”.

Body Snatchers

“Such was the happy condition of the Christian subjects of Maxentius, that, whenever they were desirous of procuring for their own use any bodies of martyrs, they were obliged to purchase them from the more distant provinces of the east.

A rich matron, Aghe, sent 3 covered wagons, 12 horsemen and a fortune in gold and silver to buy relics in Tarsus.”

– Gibbon (Decline & Fall, 15)

Body Snatchers

“Such was the happy condition of the Christian subjects of Maxentius, that, whenever they were desirous of procuring for their own use any bodies of martyrs, they were obliged to purchase them from the more distant provinces of the east.

A rich matron, Aghe, sent 3 covered wagons, 12 horsemen and a fortune in gold and silver to buy relics in Tarsus.”

– Gibbon (Decline & Fall, 15)

"Acts of Pilate"

The “Memoirs” or “Acts of Pilate,” or at least one version of them, was composed early in the 4th century by Theotecnus, Maximin’s governor in Antioch.

Their purpose was to discredit the Church using the Christian’s own weapon, “scripture.”

Theotecnus was subsequently executed by the triumphant Christians – but in an act of supreme cynicism, the pagan martyr was later transformed into an orthodox saint who had perished for his Christian faith!

Career Opportunity

Martyr’s Crown, anyone?

Organized Christian fanatics aided Constantine’s coup in 314.

In return, they were empowered as propagandists for the Christian monarchy and were rewarded with confiscated temple treasures throughout the Empire.

4th century Bishops were well-heeled, well-connected and lived in grand houses next to the main church at the state’s expense.

A triumphant State Church, lording over a disbelieving and reluctant congregation, began the process of gathering in its flock and fabricating a glorious past, the better to bring foolish pagans to the True Faith.

Every bone became a martyr and every martyr a legend of heroic death.

Career Opportunity

Stampede

“Imperial patronage colossally increased the wealth and status of the churches. Privileges and exemptions granted to Christian clergy precipitated a stampede into the priesthood.

Devout aristocratic ladies acquired followings of clerical groupies, experimented with fashionable forms of devotion.”

– Richard Fletcher (The Conversion of Europe, p38)

Business as Usual

Kind to Animals?

For more than two centuries after Christianity’s triumph the bloody entertainments of Rome continued. Indeed, during the reigns of the Christian emperors the number of offences which were punished by sacrifice in the arena actually grew.

But by the 6th century an impoverished Roman world could no longer afford its games of human and animal carnage.

Christians of a later age, never slow to turn anything to their advantage, would audaciously claim that the ending of savagery in the arena was a victory for their own purported ethics!

Slavery, inoffensive to Christian morality, of course, continued for another thousand years.

Martyrdom – the stuff that dreams are made of.