Paul in Athens? Not a chance!

We are told by the Acts of the Apostles that on his second missionary journey the apostle St Paul visited Athens. Here, supposedly, the great evangelist confounded the Greek philosophers and then left the city, never to return. And yet no Athenian Christian church sprang up. No instructive or correctional epistle came from the pen of the great missionary to any Athenian neophytes.

Despite this singular failure, the super-apostle’s so-called “Areopagus sermon” lives on in Christian tradition as a profound rebuttal of Greek philosophy. How long was Paul in Athens? It’s impossible to say. He was not driven out by popular tumult or persecution. Rather, he took himself off to Corinth where the Lord himself reassured him he would have more success (“One night the Lord spoke to Paul in a vision: ‘Do not be afraid … I have many people in this city.‘ ” – Acts 18.9-10). Why did the Lord not direct Paul to Corinth in the first place? Did the Lord want the “Areopagus sermon” to appear in the Acts of the Apostles or was that really the intention of the author of the Pauline fable?

Could it be that the truth is rather mundane, that the entire Athenian episode is invention, a symbolic story of Christian triumph over pagan error? “Athens” is not the city but the entire Greek philosophical world, rendered obsolete by the superior truths of the cross. Or so they would have you believe.

“Alone in Athens” – so just who is taking notes?

“Wherefore when we could no longer forbear, we thought it good to be left at Athens alone and sent Timotheus, our brother, and minister of God, and our fellow labourer in the gospel of Christ, to establish you, and to comfort you concerning your faith.”

– 1 Thessalonians 3.1-2.

It is commonly assumed that the testimony of Acts of the Apostles on the travels of Paul is more or less “factual”, so reasonable does it seem that a proselytizing Jew, fired up by a new faith, should have perambulated about the cities of the eastern Mediterranean. Under close inspection this assumption collapses. How, for example, does the writer of Acts know any of the material that he reports of this Athenian episode? This is not one of those “we” passages where the writer, supposedly Luke, is alleged to have been part of Paul’s entourage. Not only does Paul in his letter to the Thessalonians actually stress that he was alone in Athens but Acts itself, though moving the characters to different start positions, says the same thing!

“The word of God was preached of Paul at Berea … The brethren sent away Paul … but Silas and Timotheus abode there still. And they that conducted Paul brought him to Athens: and receiving a commandment to Silas and Timotheus to come to him with all speed, they departed.”

– Acts 17.14,15.

In Paul’s “own” chronology drawn from his epistles, when he could no longer forbear the Jews “forbidding him” to speak to the Gentiles, he takes leave of Thessaloniki. Now in Athens, Paul writes that he longs to see his “children” again but that Satan prevents his return! In his stead, Paul sends Timothy to Thessaloniki who soon returns from the 300-mile round trip with “good tidings” of their faith.

In the alternative chronology of Acts Timothy remains in Berea (Veroia/Veria) and it is unnamed “others” who take Paul to Athens, leaving him there alone but taking back a message that Timothy should join Paul (which he does – though not in Athens but in Corinth. Presumably Paul sent an angel, or a carrier pigeon, to advise Timothy of his new location).

Either way, Paul is alone in Athens when he delivers his sermon to the Athenians. So just who is taking notes?

And when was all this?

41 AD? 49 AD? 51 AD? 54 AD? Who Knows!

So poorly authenticated is Paul’s sojourn in Athens that establishing quite when he was in the city is nothing more than a pious guess.

The supposed Claudian “expulsion of Jews from Rome” (flatly denied by Cassius Dio and unsupported by Josephus) is one line in the sand, given the claim that in Corinth Paul is said to have met “Aquila and Priscilla, who had recently come from Italy.” (Acts 18.2) Paul’s presence in Athens has to precede that meeting. Claudius reigned between 41-54 AD and a “popular” date for the expulsion of the Jews is 49 AD. But Dio’s denial of the expulsion (“He did not drive them out, but ordered them, while continuing their traditional mode of life, not to hold meetings.” Roman History, 60.6.6), – far more believable – is placed at the beginning of Claudius’ reign, 41 AD. Other scholars push the date later, into the 50s.

In short, Paul’s stay in Athens floats free of any historical foundation – and thus strengthens the the probability that it is fiction.

Unnoticed by Paul

Whether as early as 41 AD or as late as 54 AD, it is rather curious that Paul betrays no awareness that the Athens he is visiting is a Roman possession undergoing reconstruction by the superpower.

“Paul” (or rather, the author of Acts) speaks of an Athens of the classical era. Back in the 5th century BC, when Athens had a population above 100,000, tribute to the city had poured in from a string of captive “allies” which, together with plunder from Persian outposts, had paid for the spectacular temples, monuments and statuary that had beautified the city in the “age of Pericles”.

But several centuries had passed and the city had far declined since her “golden age” as an imperial power. Defeated by Sparta (404 BC) and then by Macedonia (338 BC), Athens had eventually been besieged by the legions of Rome.

Greece – impoverished by war, looted by Rome

“Aristion, who violently oppressed the city, was punished by Sulla the Roman commander when he took this city by siege, though he pardoned the city itself; and to this day it is free and held in honour among the Romans.”

– Strabo (63 BC – 24 AD) Geography – IX.1

Athens had remained neutral during Rome’s Macedonian wars but then in 88 BC the city had given support to Mithridates VI of Pontus. That choice brought on a terrible retribution. Five legions under the future Roman dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla invaded Greece, drove out Mithridates, and besieged Athens. Rapidly, the region surrounding the city was reduced to a wasteland, stripped of food for the troops, sacred groves destroyed to build siege engines (both the Academy established centuries earlier by Plato, and the Lyceum of Aristotle were wrecked) and ancient temples looted. With no support coming from Italy (where he had been denounced as an outlaw) Sulla requisitioned the treasuries of Epidaurus, Olympia and Delphi to pay for his campaign.

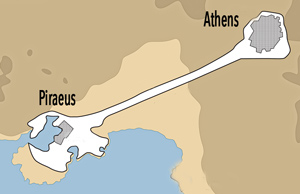

Piraeus, whose naval yards had once made Athens a great sea power, was burnt to the ground and was to remain a backwater until the modern era. The long walls which linked the port to Athens were torn down and after several months and a night attack, the starving city fell. The agora and surrounding district were extensively damaged. Pillage followed the destruction as remaining sculptures were looted and shipped back to Rome. Sulla even seized columns from the incomplete temple of Olympian Zeus for use in the Temple of Jupiter back in Rome. Desolate and largely depopulated, Athens lingered on.

Unfortunately for Greece the country continued to be a battlefield in the half-century that followed. Rome’s own civil wars – and the battles of Pharsalus, Philippi, Actium – were all fought in Greece. The consequence was that much of the country was reduced to a desert, denuded of its inhabitants. More than a century later, even Nero was moved to grant Greece immunity from Roman taxation.

At the close of the civil wars the victor, Augustus, initially punished Athens for the city’s support of Anthony by confiscating the Athenian territories of Aegina and the town of Eretria. When in 27 BC Augustus reorganized the peninsula into the province of Achaea a restored “Roman” city of Corinth became the capital. The second city of the province was Patrae, not Athens, the third Nicopolis.

But for its ancient glories and reputation as a seat of learning Athens, now deep in debt, might have followed Sparta and Thebes into oblivion.

Athens gets a Roman makeover

Romanised Athens Welcomes Philhellenic Romans!

“Captive Greeks took captive her savage conqueror, and brought civilisation to barbarous Latium.” – Horace, To Augustus (2.1.156)

From the 2nd century BC Athens had served as a retreat for Roman aristocrats when times were difficult for them in Italy. Romans in exile imbibed the cultural legacy of the Greeks, polishing their skills in rhetoric and refining philosophical argument. Eminent Romans took inspiration from faded glories. Returning to Rome, Roman aristocrats had their sons educated by Greek slaves. The epics of Homer inspired Virgil (the Aeneid). Augustus (like Julius Caesar) was an admirer of Alexander and used an image of the Greek king as a seal for his letters (Suetonius, 50.1). The dying Greek empire was an object lesson for the rising Roman empire.

A restoration of Athens began under Augustus with clearance of the area north of the Acropolis and the building of a new agora (“Market of Caesar and Augustus“) between 19 and 11 BC. This became the new commercial and trading centre of the city, a porticoed Roman-style forum. An inscription on the western gate of the forum (“Gate of Athena Archegetis“) credits both Julius Caesar and Augustus for providing the funds. Close by the eastern gate (and near the Athenian water-clock (“Tower of the Winds“) Roman engineers installed public latrines.

With essentials provided for in the new market, the area of the original agora was redeveloped into a showplace for Roman tourists. The open space of the agora was progressively filled with buildings. In the northeast corner a colonnaded basilica for use by the Roman administration was erected. This building was later enlarged and given elaborate decoration by Hadrian. Visiting Roman grandees made donations to the city, most notably the trusted lieutenant of emperor Augustus, Marcus Agrippa. He ordered the construction of a massive Odeon of Agrippa (“Agrippeion”) (15 BC), a sort of concert hall with seating for over a thousand people. The Odeon dominated the central area of what had been the old agora. On a new platform opposite the Odeon a temple to Ares, originally erected on the site chosen for the new market, was dismantled stone by stone, reassembled, and rededicated to Ares and Augustus. Caligula (37–41 AD) added a monumental staircase to the temple. An Altar of Zeus was relocated from the Pnyx to the old agora (hence, “Altar of Zeus Agoraios“): the Pnyx was a levelled and walled hill to the southwest of the Acropolis designated as a public meeting area, although in the Roman period the “popular assembly” (ecclesia) gathered in the theatre of Dionysus on the slope of the Acropolis where sacred performance gave way to crude Roman amusements. An unfinished temple from Thorikos was also re-erected in the agora to the west of the Odeon (the “SW temple“, dedicated, probably, to Demeter and Kore).

Here was a theme park suited to Roman tastes. It was a city living on the glories of its past, restored as a tourist attraction for the new Roman masters. The philosophical schools (Peripatos, Academy, Stoa, Garden) still continued but were now secondary choices to the schools of Alexandria, Antioch and Rome. One can imagine jugglers, dance troupes and Athenians on the make feigning the role of “philosophers” to earn the pleasure of their Roman visitors.

The “free city” of Athens had been redeveloped, Roman-style, long before any “Paul” ever reached the shores of Greece. In prime space in front of the Parthenon, a circular temple of Roma and Augustus had been erected, a shrine to the imperial cult that was now honoured throughout the city. From the rock called Areopagus a speaker could have looked up and seen the new temple. Yet Paul says nothing of the sacrilege.

So did any Paul ever visit Athens?

Roman Athens, circa 50 AD

So just where did Paul “reason day by day”?

Rome makes its entrance: Gate of Athena Archegetis

When Worlds Collide

A Jewish-Christian view of Athens

“Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was stirred in him, when he saw the city wholly given to idolatry.” – Acts 17.16

The author of Acts begins with an illogical assertion: that artistic representations of the divine was “idolatry”, as if the Greeks mistook their man-made effigies for the “real thing.” His “Paul” took one look at Athens and was appalled. Yet all Greeks knew that, in so far as there were gods and goddesses at all, that they did not live in temples, but on Mount Olympus! Unlike almost every other visitor to that venerable city over many centuries, “Paul’s” was the view of an uncouth, judgemental bigot. Where others saw great art and beauty, all that the Jew from Tarsus could see was “idolatry”.

But was Paul the boorish prig he appears to be or is this entire episode a literary construct? In the lands of the eastern Mediterranean the real challenge to Jewish/Christian mysticism was Greek rationalism and Athens was its historic centre. For many centuries the city had been the respected centre of learning for the ancient world. But “Paul”, salesman of divine revelation, has no interest in “mere human wisdom” – the apostle pours scorn on secular reason and empirical study at every opportunity.

“For it is written, ‘I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the cleverness of the clever I will thwart.’ Where is the wise man? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, it pleased God through the folly of what we preach to save those who believe. ” – 1 Corinthians 1.19-21

“My speech and my message were not in plausible words of wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power, that your faith might not rest in the wisdom of men but in the power of God.” – 1 Corinthians 2.1-5

The Jews had no affinity with the creative arts. They were essentially farmers, herdsmen, tinkers, traders and necromancers. Back in Judea, the impressive building program of Herod the Great had been made possible only by Greek and Roman prowess. A Jew who made his way to Athens, especially Roman Athens, would have felt adrift in an alien world – and it is doubtful that any Jews did.

No Jews and No Synagogue and in Athens in 1st century AD

“He first reasoned in the synagogue with the Jews and the devout persons.” – Acts 17.17

Bizarrely, the evidence presented by Jews today for a Jewish presence in ancient Greece at the dawn of the Christian era is the Christian Acts of the Apostles. This imaginative tale asserts that everywhere that Paul went he found a synagogue and an active community of Jews in attendance. That claim fits nicely into the glib and oft repeated assertion that Jews were “everywhere”, in “all cities”, and were numerous “across the entire world” – a sentiment echoed by Christians and occasionally by Roman writers exasperated by that troublesome race.“When, meanwhile, the customs of that most accursed nation have gained such strength that they have been now received in all lands, the conquered have given laws to the conquerors.” – Seneca, as quoted by St Augustine (The City of God, 6,11). And yet aside from the hyperbole, there is no real evidence for Jews in 1st century Athens at all.

If, as Paul says, the city was “wholly given to idolatry” surely that did not include idolatrous Jews? And if there were no Jews was there a synagogue?

In 1977 a marble fragment – about the size of a hand – and apparently incised with a seven-branched Menorah and a palm branch indicated a “possible” synagogue in the agora. But it was dated no earlier than the late 4th century AD. Nothing has ever been found to suggest a 1st century synagogue for any St Paul to have visited. In fact, placement of a cult shrine in the agora was indicative of its importance to the Athenians and the alien Jewish god Yahweh would never have qualified. The 2nd century Greek geographer Pausanias (Description of Greece) writes at length of the sites of Athens, and is especially interested in the sacred. Yet Pausanias says nothing of any synagogue. Nor does he comment on the presence of any Jews in the city.

This tiny fragment of marble appears to depict a crudely incised menorah flanked by a palm branch. It has been dated to the late 4th/ early 5th century AD, a degenerate era which followed the sacking of Athens by Herulians (267 AD) and Visigoths (396 AD).

The fragment (8.5 cm by 8 cm) was recovered from the agora during excavation in the summer of 1977. It is speculatively thought to be from a frieze above a doorway. But was this really “good enough” for a synagogue? It is also unlike the vast majority of inscribed menorahs and may even have no connection with Jewish symbolism at all. Equally possible is that the fragment was a keepsake or lucky charm, the icons scratched onto the stone by a Jew who found himself among the ruins.

Further conjecture is that one of the four chambers of the ruined ancient Metroon (a temple of Meter, the Mother of the Gods, and a state archive) had been restored as a synagogue – a wildly unlikely scenario in a city forcibly converted to Christianity only recently!

In any event, the fragment certainly provides no support for a Jewish synagogue existing centuries earlier.

Today, there are about 8,000 Jews in Greece, a country with a population of around eleven million. The American Jewish ADL has described Greece as the most anti-Semitic country in Europe. Greek antipathy towards Jews stretches back to antiquity and the reasons are not difficult to fathom. The creative genius of the ancient Greeks found little of interest in these peculiar and barbarous orientals, in thrall to a violent and egotistical deity. The two races met initially in war. After two centuries as a vassal state of Persia, when Alexander marched east Judah capitulated without a fight and found itself a minor possession of the Macedonian conqueror. The Greeks recruited Jewish mercenaries into their army, planted their cities across the Levant, and moved on.

On the other hand Greek influence on the Jews was profound, creating “Hellenists” among them. Some Jews, certainly, dispersed into the Hellenistic world, adopting Greek names and customs, and giving birth to a new literature. Hellenism altered and invigorated the culture of the Jews, producing, ultimately, a new syncretic religion. Sparse evidence suggests that the Hellenist Jews followed the trade routes and were to be found in many port cities of the eastern Mediterranean. But Athens was NOT one of them.

Jewish escape route?

After conquest by the Greeks the Jews were split between modernizing Hellenists and religious reactionaries, with each side divided into multiple factions (Tobiads, Oniads, etc.). A civil war during the Hasmonean era appears to have caused some Jews to flee to the safety of the Greek ports of the Aegean (1 Maccabees 15). Others were sold to the Greeks as slaves. Slaves of Judean origin are known from inscriptions from 2nd century BC Delphi.

Delos is notable in that it had a thriving slave market. For a time, it was thought to have the ruins of the oldest synagogue in Europe. Recent evidence, however, identifies the synagogue with Samaritans not Jews.

In the Augustan age some Jews made their way to the new Roman colonies of Corinth, Patras, and Nicopolis. Athens, however, did not attract Jews.

Paul teaches wisdom to the philosophers of Athens? Fat chance.

“Also some Epicurean and Stoic philosophers debated with him. Some said, “What does this babbler want to say?” Others said, “He seems to be a proclaimer of foreign divinities.””

– Acts 17.18

From its inception Christianity claimed an absolute and revealed truth so what need was there for scientific enquiry (“vainly puffed up fleshly mind”)? But the Greek philosophers espoused their own systems based upon observation of the world and rational argument. That they should give rapt attention to an alien Jew – Epicureans and Stoics together, no less! – seems rather unlikely, particularly as all that “Paul” has to say is exceedingly simplistic and is little more than a proclamation that his god was the real god.

Did “Paul” really target Epicureans and Stoics?

We are told that it was “certain Epicurean and Stoic philosophers” that took Paul to the Areopagus and yet Paul begins by reproaching his audience as “very religious”, or as alternative translations would have it, “too superstitious” (δεισιδαιμονεστέρους). What an extraordinary charge to put before Epicureans, sober rationalists and to all intents, atheists. For them, the gods – if they existed at all – did not create the universe and lived unconcerned about the lives of men. Nor were the Stoics starry-eyed mystics, besotted with the irrational. For them, “god” was a rationalism or “logos” that permeated all things. And Paul, the man who claimed to hear the voice of god guiding and directing him, had the audacity to tell the philosophers they had too much religion? It is beyond all credibility that Epicurean and Stoic intellectuals would have given the time of day to a Jewish guru who made only irrational assertions.

The Greek philosophers have simply been used by the author of Acts to set up a pseudo-trial. The real target of the so-called “speech” are the “Men of Athens” – that is, the mass of non-elite polytheists. As the frontman of Christianity, the “Paul” of Acts is making a direct appeal to Greek pagans who, in time, will be force-fed Christian dogma. Christianity was not interested in a debate with Greek rationalism – it was fanatically determined to destroy it. For “Paul” and the author of Acts philosophy was a dangerous deceit.

“God’s mystery of Christ in whom are hid all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge. I say this in order that no one may delude you with persuasive words …

Beware that no one spoil you by philosophy and vain deceit, according to the tradition of men, according to the elemental spirits of the universe, and not according to Christ … Let no man beguile you of your reward in a voluntary humility and worshipping of angels, intruding into those things which he has not seen, vainly puffed up by his fleshly mind.”– Colossians 2.2,18

In time, Christianity absorbed what it could not defeat. The language and methods of Greek rationalism – in particular its final flowering in Neoplatonism – became the raw material out of which Christian theology was fashioned. Never restrained by consistency or logic, later defenders of the faith would claim that not only “Paul” but the godman himself was, in fact, a philosopher!

“Nobody can deny that our Saviour and Lord was a philosopher and a truly pious man, no imposter or magician.”

– Eusebius, Demonstration of the Gospel, 3.6.8

Between a rock and a hard place

“And they took him, and brought him to the Areopagus, saying, May we know what this new doctrine is which you present? For you bring some strange things to our ears: we would like to know therefore what these things mean. For all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing. Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars’ hill, and said, Men of Athens, I perceive that in all things you are too superstitious.“

– Acts 17.19-22

It seems Paul was “taken and brought” before the Areopagus (the Greek words used are epilabomenoi te autou – “getting hold of him”). So was Paul under arrest and was this some sort of trial? At this point it looks that way. But then would philosophers really act like police officers? Was the reference to the Areopagus a reference to the venerable court or merely to the rock from which the court took its name? And then we have the dramatic composition, Paul stands “in the midst of them” and starts to speak. It is Paul who is determining the pace of events. So is this a really a public address and not any sort of trial? And when Paul has finished, he departs again from the “midst of them“.

All very theatrical. And all very bogus,

“In the midst” ?

In the fantasy world of the Christian imagination Paul “out philosophises” the Athenian philosophers with barely 200 words. The enthusiasts for Jesus, however, can’t agree whether the multitude gathered in a basilica or on the top of a sacred rock!

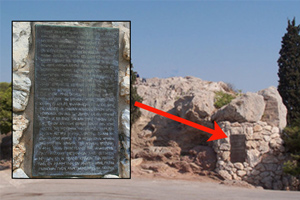

The rock favoured by Christian literalists – Mars Hill (Areopagus)

‘Proof’ has been created by 20th century Christians. What more evidence do you need than a brass plaque etched with Paul’s “Areopagus sermon”?

The portico favoured by Christian artists and scholars – Stoa Basileios

The Royal Stoa is regarded as a more appropriate venue than a rock for Paul’s important address to the philosophers.

Areopagus – The Hill of Mars

The rocky outcrop at the foot of the Acropolis, the Areopagus.

With its irregular surface and dangerously sheer sides, exposed to wind and inclement weather making standing and hearing difficult, the Areopagus was scarcely conducive to any but the smallest public meeting. Paul’s “surrounding crowd” (“in the midst“) could never have been accommodated on the hilltop. The ancient court, which took its name from the Areopagus, had a membership of about 150 members drawn from retired archons (annual rulers of the city). But it had been deprived of almost all of its functions in the democratic reforms of 462 BC in favour of another court, the popular tribunal, the Heliaia. From that time on, the remit of the Areopagus had been restricted to cases of non-political murder of Athenian citizens. By the Roman era the court of the Areopagus had little authority, met rarely, and did so in a basilica. Though the city was “free” and nominally still ruled by archons, Roman governors themselves sometimes took the role of archon. In any event, Augustus sharply curtailed the powers of the various assemblies.

Christians have always exaggerated the importance of both the rock and the antique court named after it. By so doing they give support to the claims made in Acts regarding Paul’s supposed sermon.

“At Athens may still be seen a most curious relic of antiquity – the roof of the Areopagus, composed of mud.”

– Vitruvius, on Architecture, 2.1.5. 1st c. BC

Murder, Trial and Punishment

The Areopagus had long been associated with Greek mythology. It was so-named as the place where the god Ares had been put on trial for the murder of Poseidon’s son Alirrothios. The Areopagus is also mentioned by Aeschylus (“The Eumenides“, 458 BC) as the place where Orestes was tried for the murder of his mother.

One cave cut into the limestone was identified with the Furies (Erinnyes). In fable, these three old crones (more ancient than Zeus himself) were the infernal avengers, relentlessly hounding the guilty. In practice, – given the sheer sides of the rock – one suspects that if an ancient court ever met on the hill, those found guilty were hurled to their death, just as they were from the Tarpeian Rock in Rome.

Unknown “Unknown God”!

No altar with the inscription “to an unknown god” has ever been found in Athens!

“Then Paul stood in front of the Areopagus and said, “Athenians, I see how very religious you are in every way. For as I passed along and observed the objects of your worship, I found also an altar with this inscription: ‘To the unknown god.’ ” – Acts 17.22,23

“No evidence has yet been found for the existence of any such dedication. When authors refer to ‘altars of unknown gods’ they appear to mean altars without a dedication to a named deity.” – G. Lampe, Peakes Commentary on the Bible, Acts 17.

The Areopagus sermon is the longest of Paul’s supposed speeches. Even so, it is only about 270 words in English or just 193 words in the original Greek. Scarcely more than a paragraph, the “sermon” takes approximately two minutes to deliver, less time than it takes to climb the hazardous steps of the Areopagus. As many scholars observe, the “Paul” who speaks in Athens is very different from the apocalyptic bully who condemns the wickedness of paganism in his letters. At best, what we have here is conjectured “highlights” from someone who was not himself a witness.

The content is disjointed nonsense assembled around a blatant falsehood: that the Athenians confessed themselves to be “ignorant of god” and Paul, of course, was there to put them straight.

How does the author of Acts derive this startling confession? With a sleight of hand in which a literary reference to “gods unknown” becomes an “inscription to an Unknown God”!

“Paul” apparently found an altar inscribed “To an unknown god” – a remarkable discovery considering that no one else ever has. Of tens of thousands of Greek inscriptions not one has ever been found thus inscribed. And why would it be? The Greeks knew their gods. But altars might be uninscribed and with the trend within Neoplatonism to resolve the multiple gods of polytheism into a single all-embracing deity, altars lacking any inscription had become a commonplace. That observation is found in literature from the period – literature available to the author of Acts.

In particular, the author of Acts would have been aware of a folktale in which plague in 6th century BC Athens had been eliminated by Epimenides, a hero of Crete. Apparently, Epimenides ordered sacrifices on altars without inscriptions. The yarn was later presented as history by Diogenes:

“When the Athenians were attacked by pestilence …they sent a ship … to Crete to ask the help of Epimenides. … He took sheep, some black and others white, and brought them to the Areopagus and … instructing those who followed them to mark the spot where each sheep lay down and offer a sacrifice to whichever local divinity. And thus, it is said, the plague was stayed.

Hence even to this day altars may be found in different parts of Attica with no name inscribed upon them, which are memorials of this atonement.”

– Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 1.10. (c 230 AD)

From “no name inscribed” and “gods unknown” the deceitful author of Acts conjures up an inscribed altar to a single “Unknown God” – and has his Paul reveal to the ignorant philosophers that their hidden deity is none other than the Jewish god Yahweh!

That this folktale is the origin of “altars of unknown gods” is made more certain by Acts 17 actually quoting from a poem of Epimenides (a poem also quoted in the epistle to Titus). Paul – who claimed to have excelled all his peers in knowledge of the Hebrew texts, who spoke the native Lycaonian language in the uplands of Anatolia, was evidently now comfortably at home with Greek literature and able to quote freely from the Greek poets.

As if.

Where DID they get their ideas from? | ||

They fashioned a tomb for you, holy and high one, Never, O men, let us leave him unmentioned, – Aratus, Phaenomena 1-5 | ||

For in him we live, and move, and have our being; as certain also of your own poets have said,

For we are also his offspring.

– Acts 17.28

Same poem also used again by the author of Titus:

One of themselves, a prophet of their own, said, The Cretians always liars, evil beasts, slow bellies.

– Titus 1.12

The Areopagus sermon

“In fact the speech is probably a composition by Luke, using much standard material from Jewish and Christian apologetic against polytheism.”

– G.W.H. Lampe, Peakes Commentary on the Bible, 914

Athenian philosophers would not have warmed to Paul’s misrepresentation of “gods unknown.” So why would “Paul’s audience” have listened to this nonsense? The writer of Acts holds the drama together by depicted the philosophers as infatuated by novelty and it seems to them that Paul has “a new god” – or as later Christians would argue, “two new gods”, Jesus and the Resurrection!

From as early as 5th century and patriarch John Chrysostom, Christian apologists have suggested that the not-so-smart philosophers of Athens thought that Paul was speaking about two gods, Jesus “the male deity” and “Anastasis” (Resurrection) “the female deity”. Silly billies.

Paul goes on to make several unconnected points: God made everything; God does not need anything; God is close; universal brotherhood (“from one ancestor”). Having made these trite assertions “Paul” issues a threat: God had hitherto “overlooked” human ignorance but now “he has appointed a day on which he will judge the world.”

With that, the mighty apostle from Tarsus makes his exit!

Note that there is no reference in the speech to an earthly ministry of Jesus the godman, only that God had ordained as his judge “a man that he had raised him from the dead”. But Paul does not even name this man.

The readers of Acts rely on earlier references to Jesus Christ to know who this judge-elect is but “Paul’s audience” in Athens – if it had ever existed – would have been in the dark unless they had been party to Paul’s earlier disputations in the market place. Recognizing this illogicality, the author of Acts has “some” of his listeners unwittingly state the Pauline mission: “because he preached Jesus and the resurrection.” (Acts 17.18)

There is no explanation as to how Jesus had lived on earth or died on the cross, no mention of how this man – whoever he was – “fulfilled prophecy“. Paul doesn’t even claim that the man was the “Son of God”.

The writer of Acts is not working from the gospels here but from a wholly different source.

Sermon or Subterfuge?

“What therefore you worship as unknown, this I proclaim to you.

The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man. nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything.

And he made from one man every nation of mankind to live on all the face of the earth, having determined allotted periods and the boundaries of their dwelling place, that they should seek God, and perhaps feel their way toward him and find him.

Yet he is actually not far from each one of us, For in him we live, and move, and have our being; as certain also of your own poets have said, For we are also his offspring. Forasmuch then as we are the offspring of God, we ought not to think that the divine being is like gold or silver or stone, an image formed by the art and imagination of man.

And the times of this ignorance God overlooked but now commands all men everywhere to repent: Because he has appointed a day, in the which he will judge the world in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed; and of this he has given assurance to all by raising him from the dead..

And when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked: and others said, We will hear thee again of this matter. So Paul departed from from their midst..”

– Acts 17.23-33

Source of the story

The Trial of Socrates

There are many curious parallels between the “trial of Paul before the Areopagus court” and the trial of Socrates four-hundred years earlier.

We have two extant sources for the latter: the Apology of Plato and the Memorabilia of Xenophon. These accounts were among numerous reports of the trial available to the author of Acts and there can be no doubt that he derived inspiration for the “trial of Paul” from the famous story of Socrates.

• The “charge” levelled at Paul was identical to that levelled at Socrates – introducing foreign gods (Plato, Apologia, 24).

• Socrates, like Paul, expounded his views in the market place before “going to trial”.

• Socrates, like Paul, heard the voice of God.

• Socrates, like Paul, feared “unrighteousness” more than death.

• Socrates, like Paul, quoted poets.

• Socrates, like Paul, believed judgement would be from “righteous sons of God.”

• Socrates, like Paul, was no democrat or egalitarian. He believed that the common people were like sheep, in need of firm direction by a wise shepherd.

The autocrat from Tarsus would have wholeheartedly agreed!

Where DID they get their ideas from?

Socrates

The charge: Not paying respect to those gods whom the city respects and introducing other new deities.

Behaviour: He was constantly in public … when the market was full he was to be seen there … discourse with all who were pleased to hear him.

He did not dispute about the nature of things as most other philosophers disputed … but endeavored to show that those who chose such subjects of contemplation were foolish.

He directed his inquiries to the consideration of the divine power, the nature of man, the connection of the human with the divine nature, and the government of the world by divine influence.

– Memorabilia of Xenophon

Defiantly unapologetic

“Men of Athens …

Athenians, I am not going to argue for my own sake, as you may think, but for yours, that you may not sin against the God, or lightly reject his boon by condemning me.

Poets write poetry, but by a sort of genius and inspiration; they are like diviners or soothsayers who also say many fine things, but do not understand the meaning of them.

An oracle or sign which comes to me, and is the divinity which Meletus ridicules in the indictment. This sign I have had ever since I was a child. The sign is a voice which comes to me …

I cared not a straw for death, and that my only fear was the fear of doing an unrighteous or unholy thing.

I do believe that there are gods, and in a far higher sense than that in which any of my accusers believe in them. And to you and to God I commit my cause …

Death is the journey to another place … the pilgrim arrives in the world below, he is delivered from the professors of justice in this world, and finds the true judges who are said to give judgment there, Minos and Rhadamanthus and Aeacus and Triptolemus, and other sons of God who were righteous in their own life …

– Apology of Plato

Paul

The charge: “He seems to be a proclaimer of strange gods “

Behaviour: “He disputed in the market daily with them that met with him.”

Foolish philosophers: “For all the Athenians and strangers which were there spent their time in nothing else, but either to tell, or to hear some new thing.”

“God that made the world and all things therein, seeing that he is Lord of heaven and earth“

Defiantly unapologetic

“Men of Athens …

God gives to all life, and breath, and all things;

And hath made of one blood all nations of men for to dwell on all the face of the earth

For ‘In him we live and move and have our being’; as even some of your own poets have said, ‘For we too are his offspring.’

God I declare unto you

That they should seek the Lord ..

Forasmuch then as we are the offspring of God, we ought not to think that the Godhead is like gold, or silver, or stone, graven by art and man’s device.

God commands all men everywhere to repent:

He has fixed a day on which he will have the world judged in righteousness by a man whom he has appointed,

– Acts 17

Source of the story

The Trial of Socrates

There are many curious parallels between the “trial of Paul before the Areopagus court” and the trial of Socrates four-hundred years earlier.

We have two extant sources for the latter: the Apology of Plato and the Memorabilia of Xenophon. These accounts were among numerous reports of the trial available to the author of Acts and there can be no doubt that he derived inspiration for the “trial of Paul” from the famous story of Socrates.

• The “charge” levelled at Paul was identical to that levelled at Socrates – introducing foreign gods (Plato, Apologia, 24).

• Socrates, like Paul, expounded his views in the market place before “going to trial”.

• Socrates, like Paul, heard the voice of God.

• Socrates, like Paul, feared “unrighteousness” more than death.

• Socrates, like Paul, quoted poets.

• Socrates, like Paul, believed judgement would be from “righteous sons of God.”

• Socrates, like Paul, was no democrat or egalitarian. He believed that the common people were like sheep, in need of firm direction by a wise shepherd.

The autocrat from Tarsus would have wholeheartedly agreed!

Failure in Athens, Triumph in Greece

“And when they heard of the resurrection of the dead, some mocked: and others said, We will hear you again of this matter. So Paul departed from among them. Howbeit certain men clave unto him, and believed: among which was Dionysius the Areopagite, and a woman named Damaris, and others with them.”

– Acts 17.32-34

Rather curiously Paul supposedly made one spectacular convert as a result of his two-minute sermon, Dionysius the Areopagite – in other words, a member of the court itself (not a philosopher then!) who just happened himself to have the name of a dying-and-rising Greek god!

Writing centuries later, church historian Eusebius would have us believe that another Dionysius (this one the pastor of Corinth) vouched that his earlier namesake had indeed been “the first bishop at Athens” – pretty impressive considering that the Areopagite had no congregation, no church, and this was a century before bishops appeared! Despite the claim made in Acts, another “tradition”, however, gives this honour to “Hierotheos the Thesmothete” (a junior ruler or Archon). Adding to the melee, a 5th century Neoplatonist, himself called Pseudo-Dionysius described Hierotheos (or perhaps, a Pseudo-Hierotheos!) as a divinely inspired hymnographer !

Just as odd (and perhaps indicative of a later redaction) is the naming of a second convert, a woman named Damaris, “and others“, with no further details and no known history. Damaris is a Greek adaptation of the Jewish name Thamar or Tamar (the biblical whore who produced an ancestor of Jesus by her father-in-law). 4th century bishop Chrysostom made the claim that Damaris had been the wife of Dionysius, an obvious fancy.

In truth, the converts are invention and the reference to an “Areopagite” is only made to give a triumphant ending to a “mission” that never occurred and had no legacy. As the modern author Marios Verettas remarks: “Members of the Areopagus would never be called by their title of ‘judges of impure crimes’, but would prefer to be called by their highest honorary distinction, which was that of an Archon.”

The Athenians were unmoved by any mystic from the Levant. It is perhaps significant that having given a “solid response” to Athenian rationalism, the hero of Acts goes off to Corinth determined to “know nothing but Jesus Christ, and Him crucified“.

The Church Militant

First church in Athens

“No city resisted Christianity as long or with such a sense of intellectual superiority.“

– Green, The Parthenon

In reality, Christianity had no significant presence in Athens for centuries. Even after Constantine, and the religious revolution that convulsed the ancient world, Athens held tenaciously to Greek rationalism. Matters began to change when a young Athenian girl, Athenais, was presented to the Empress Pulcheria in Constantinople. Athenais was the daughter of a wealthy pagan philosopher and had been named for the goddess Athena herself. Pulcheria, a Christian fanatic, had been ruling as regent for her younger brother for years and was searching for an agreeable bride for the future Theodosius II. Athenais was chosen and church patriarch Atticus was assigned the task of impressing upon the girl the errors of paganism. She emerged as a committed Christian and future empress with the name Eudocia.

The marriage was in June 421. Keen to prove her fidelity to Christ, Eudocia authorised the construction of the first church in Athens. In a tragic irony, it was raised within the ruined edifice of the Library of Hadrian, a once magnificent cultural centre, equal in size to the adjacent Roman agora. By then, what remained of Hadrian’s main library building had been re-purposed as part of the “late Roman” wall that protected the tiny inner city and served as a garrison for the local militia. Eudocia’s church took the shape of a Greek cross (tetraconch) and was built over what had once been the central ornamental pool.

The ancient Panathenaic Way, which had run diagonally across the ancient agora and up to the Acropolis, now disappeared in favour of a new road which ran directly to the church. The symbolism was palpable. The politically-savvy girl was making clear to her fellow Athenians that Christianity was in command and the old gods were dead. Thereafter, for centuries, the only substantial buildings to be built in Athens would be churches. The hungry, if unwashed, inhabitants sank silos for storing cereal into the floor of the Roman bathhouses. All the temples of antiquity, including the Parthenon itself, the Erechtheum, the Temple of Hephaistos, were reconsecrated to the Christian godman. The light of reason had died in the city of wisdom.

The final blow was delivered by the Christian emperor Justinian who closed forever the schools in 529/532. The last scholar, a Neoplatonist named Damascius (458-538), fled to Persia. In 515. He had written a biography of Hypatia, the last head of the Library of Alexandria, murdered by Christian fanatics. The curious Pseudo-Dionysian writings may be his work – “the last counter-offensive of paganism” – Neoplatonism smuggled into Christian theology when all else had been lost.

Not one to miss a trick, Justinian had columns from the ancient agora transported to Constantinople for use in his construction of St Sophia. The decline of Athens was assured.

2nd century Athens

Athens was extensively rebuilt and enlarged by Emperor Hadrian (117-138 AD). This was at the apogee of Pax Romana.

5th century Athens

Athens had been devastated by Germanic Herulians in 267 AD and Visigoths in 396 AD. The city withdrew within walls which protected just a small area north of the Acropolis. Outside the wall, the city had been bandoned,

Twilight

In Acts of the Apostles, Athens is not the town but a metaphor for the entire Greek philosophical tradition; in other words, rational thought.

Paul, the fictitious prophet of the new revelation, is now presented as a “philosopher” – in fact, a great philosopher. He first preaches in a nonexistent synagogue to indicate to the reader that the “mission to the Gentiles” is still proceeding. The Athenian philosophers are then decried as “novelty-obsessed” (for, in the eyes of men of faith, that is all that rational empiricism amounts to, an affectation of leisured elites). These intellectuals regard Paul as a “babbler”, a purveyor of second-hand scraps. But they are too clever by far. God’s sublime truth is revealed to those of child-like minds, undisturbed by the wisdom of men. Taken before a court which symbolizes the revered and most ancient traditions of Athenian culture, the apostle sets at nothing the wisdom of men and the accomplishment of centuries.

With the stern warning that his god now demands repentance and that a judgement day has been set for all men, the uncompromising apostle exits the stage.

Theatre – but not history.

Sources:

Alkistis Choremi, The Roman Agora: the first commercial centre of Athens, Archaeology of the City of Athens

Geoffrey C. R. Schmalz, Augustan and Julio-Claudian Athens: A New Epigraphy and Prosopography ( Brill (2008)

MC Hoff and SI Rotroff (eds.), The Romanization of Athens (Oxbow Monographs, 94), 1997

Marios Verettas, The Suspicious Visit of St Paul in Athens (Veretta, 2001)

Jacobus Bloomfield (ed.), The Greek Testament, Volume 1 (Brown, Green & Longmans,1845)

Stewart Perowne, Death of the Roman Republic (Hodder & Stoughton, 1969)

Vanessa A. Champion-Smith, Pausanias in Athens: An Archaeological Commentary (UCL, 1998)

C. Fant, M. Reddish, A Guide to Biblical Sites in Greece and Turkey (OUP2003)

Project Athens Agora

Ancient Athens 3D

Archaeology of the City of Athens

Athena – Warrior Goddess of Wisdom

Not for Paul – Not for Jews

Athena Parthenos, the virgin goddess. Her temple, the Parthenon, served as treasury of the Athenian Empire (5th-4th centuries BC).

A temple to Augustus and the imperial cult was erected in front of the Parthenon in the 1st century BC.

In the 6th century AD the Parthenon was vandalised by Christians and converted into a church dedicated to the Virgin Mary (“Mother of God”)..

Slippery when wet

Areopagus – looking east towards the Acropolis. The name Areopagus survives today as the title of the Supreme Court of Greece.

Athens-on-Sea

To provide Athens with secure access to the sea, 6 km walls were constructed from the city to its port at Piraeus. Here was housed the massive Athenian fleet which allowed the city to be the naval superpower of antiquity.

The Roman general Sulla destroyed the long walls during his siege of Athens (87–86 BC) and Piraeus was razed to the ground. It remained a backwater for nearly two millennia. When the starving city fell, much of Athens was destroyed.

The Pnyx – arena for the first democratic assembly

The Jews of Greece

“Most ancient synagogue in Europe”

Mosaic floor of a simple rectangular synagogue on the island of Aegina (27 km south of Athens. Unfortunately for the fans of Paul, it is dated to the 4th century AD.

Another “oldest synagogue in Europe”, this one on the island of Delos. However, inscriptions found in the 1980s indicated that the building had been used not by Jews but by Samaritans.

“First Jew” in Greece not a Jew

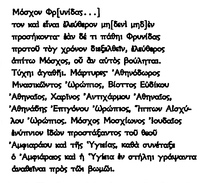

Inscription from Oropos (near Athens) referring to a slave “Moschos, son of Moschion the Jew” dated to 3rd century BC.

This particular Jew (with a Greek name) records that he set up the stone commemorating his freedom under the direction of the pagan gods Amphiaraos and Health!

Romaniote Jews, who take their name from the Byzantine “Romaioi”, have a tradition that they arrived in Epirus (northwest Greece) after the destruction of the temple in 70 AD – too late for Paul to lecture them in any synagogue!

Epicureans

Essentially atheistic, Epicureans believed that both body and soul ended with death. Epicurus himself reasoned that the individual should avoid pain (including fear of death) and seek rational understanding of the world.

“When we say that pleasure is the goal we do not mean the pleasures of the dissipated and those which consist in the process of enjoyment … but freedom from pain in the body and from disturbance in the mind.

For it is not drinking and continuous parties nor sexual pleasures nor the enjoyment of fish and other delicacies of a wealthy table which produce the pleasant life, but sober reasoning which searches out the causes of every act of choice and refusal and which banishes the opinions which give rise to the greatest mental confusion.”

– Epicurus, Letter to Menoecus

Stoics

Stoicism was pantheistic, identifying an all-pervasive rationale or “logos” in all things. The only goal, therefore, was to live in agreement with the logos, a philosophy well adapted to the Roman sense of duty and forbearance. At death the soul, but not the body, was re-absorbed into the cosmos (or “primeval fire”). The logos of the Stoics would never incarnate as a man.

“The Stoics hold that the universe has two principles … The passive one is matter, the active is reason that inheres in matter, that is God … God is one and the same with Reason, Fate, and Zeus ; he is also called by many other names.”

– Diogenes, Lives of the Philosophers, 7.134,135

Paul doesn’t give Platonists, Neoplatonists and Peripatetics a mention!

Here

“Then Paul stood in the midst of Mars’ hill, and said, Ye men of Athens, I perceive that in all things ye are too superstitious.”

– Acts 17.22 (King James Version)

There

“In the first century A.D. the Council met in the Agora, before the Stoa Basileios.”

– F. F. Bruce, The Acts of the Apostles, 335.

An altar without an inscription might in a later age be used as a pedestal for a statue.

NOT Greek,

NOT inscribed to “an Unknown God”,

NOT Evidence

A “favourite” of the godly is this 2nd c. BC Roman altar from the Palatine, restored and inscribed in Latin “sacred whether to a god or goddess“.

SEI·DEO·SEI·DEIVAE·SAC

G·SEXTIVS·C·F·CALVINVSPR

DE·SENATI·SENTENTIA

RESTITVIT

Close enough? Not nearly.

Prototype

A “prototype” for the Areopagus sermon, in fact, is to be found earlier in the book of Acts when Paul and Barnabas are supposedly in Lystra (in southwest Anatolia).

Lystra stands out as the first town Paul encountered with an entirely pagan population. Here Paul heals a cripple by shouting, argues in the Lycaonian language, and gets mistaken for a god!. He instantly recovers from a “fatal” stoning and takes to the road the next day none abashed!

But the dialogue rehearses the argument, used later in Athens:

“Don’t worship man-made things, God will no longer tolerate you ignoring his comman

At Lystra

“Men, why are you doing this? We are mortals just like you, and we bring you good news, that you should turn from these worthless things to the living God, who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them.

In past generations he allowed all the nations to follow their own ways; yet he has not left himself without a witness in doing good—giving you rains from heaven and fruitful seasons, and filling you with food and your hearts with joy.”

– Acts 14.15-17.

At Athens

“God that made the world and all things therein, seeing that he is Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in shrines made by man,

Being then God’s offspring, we ought not to think that the Deity is like gold, or silver, or stone, a representation by the art and imagination of man.

And the times of this ignorance God overlooked, but now he commands all men everywhere to repent;

– Acts 17.24-30

Socrates hears God

“God has given me through the oracles’ voice, through that of dreams and through all the means no other heavenly power has ever used to communicate its will to a mortal.”

– Plato, Apology 33

Paul hears God

“Then spoke the Lord to Paul in the night by a vision, Be not afraid, but speak, and hold not your peace.”

– Acts 18.9

“Athens” + “Agora” =

ATHENAGORAS ??!!

A supposed Athenian “philosopher who became a Christian” was Athenagoras (late 2nd century?), whose life is completely unknown.

He is unmentioned either by Eusebius or Jerome though 5th century Philip of Side claimed Athenagoras “converted from paganism after reading the gospels.”

Which makes it all rather curious that in his defence of the Resurrection, Athenagoras failed to make any reference to the scriptures at all!

Highs and Lows

A remnant of Hadrian’s Library – and a later church

“Emperor Hadrian, a benefactor to all his subjects and especially to the city of the Athenians.”

– Pausanias, Description of Greece, Attica, 1.3.2

The so-called Library of Hadrian – it was actually rather more of a cultural centre – was one of the most impressive and luxurious buildings ever built by that emperor. Monumental porticoes flanked a large central hall. It was described by Pausanias (I.18.9) as having one hundred columns of Phrygian marble, a gymnasium and a gilded roof.

As well as library, the complex appears to have served as forum, records office, administrative centre and as a sanctuary to the imperial and other cults.