Miniscule – Karl the Big tries hard to write joined up letters

THIS PAGE IS SOMETIMES USED TO TEST UPDATES! And it is today July 23, 2014

Miniscule – The 'Carolingian Renaissance' contribution to civilization

In the ruins of the western empire the formal script of the Romans – square capitals – was to be found on imperial buildings everywhere. But the Latin literary, or book hand, had disappeared. Use of the old un-spaced capital script – ‘uncial’ – though attempted, made for ponderous communication.

When, at the end of the 8th century, the warlord Charlemagne established his impoverished ’empire’, he ruled a vast, disparate realm, populated by the descendants of many races – Franks, Romans, Goths, Lombards, Burgundians, Saxons etc. – who spoke several different tongues.

So barbarized had western Europe become that Christian doctrine itself was fragmenting. In a number of scattered monasteries, several ‘national’ styles of Latin cursive had emerged – Italian, Merovingian, Visigothic, Germanic, and Anglo-Irish. Each was a ‘monastery dialect’ – an idiosyncratic attempt to ease the laborious process of copying manuscripts, a labour in which ‘illumination’ – pretty pictures and calligraphy – took precedence. Even the graphic art forms are not original but were a throw back to a prehistoric art of the pre-Christian era.

Copying without comprehension centuries-old literature, adding a little animal here, a fanciful capital letter there, became the highest achievement of this degenerate age. The supposed sacred texts of the Bible now existed in myriad local variations. Most clerics were illiterate anyway, and access to scripture was forbidden to the lay-person. Within gem-overlaid covers and smothered by a riot of calligraphy, lay the cold corpse of a language.

Charlemagne, favoured son of the papacy, was committed to imposing Roman Catholicism wherever his influence could reach. He feared ‘heresy’ could emanate not only from the mouths of pagans (who would either convert or be killed) but also from ignorant priests who could not read their own scriptures.

” For when in the years just passed letters were often written to us from several monasteries … we have recognized in most of these letters both correct thoughts and uncouth expressions … Whence it happened that we began to fear lest perchance, as the skill in writing was less, so also the wisdom for understanding the Holy Scriptures might be much less than it rightly ought to be … “

– Charlemagne, letter to Baugulf, abbot of Fulda.

A series of decrees or ‘capitulars’ were issued which threatened clerics with loss of office if they failed to acquire an ability to read and write. Bishops supposedly had to ascertain compliance, though they might themselves have been illiterate.

Charlemagne set out to impose a standardised Vulgate Bible, a standardised Benedictine Rule and a standardised liturgy but to achieve this he needed a standardised written language. The warlord found his man in Alcuin, a refugee from war-ravaged England, and severely orthodox churchman.

Alcuin and his monks (in the first ‘cathedral school’) poured through all the classical works of antiquity they could find for the inspiration for a new script.

“I, your Flaccus, according to your exhortation and encouragement … am eager to inebriate others with the old wine of ancient learning …”

– Alcuin of York, letter to Charlemagne

As a result, Carolingian minuscule developed, a familiar combination of capital and small letters with most of the decorative flourishes and ligatures eliminated.

As monastic agents expanded their activity – for example, into England in the 10th century and into Spain in the 11th century, Carolingian minuscule became the written language of oppression and religious orthodoxy.

It became the official script and literary hand of the Frankish Empire. From it emerged all the later ‘Gothic’, ‘Roman’ and ‘Humanist’ scripts, still in use today.

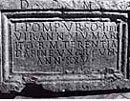

Roman majuscule – all capitals, as befit the majesty of Rome.

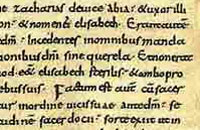

Carolingian minuscule – a cursive script developed for the imposition of orthodoxy.

By Charlemagne’s time, people had come to believe that physical objects associated with saints, or even parts of the bodies of the saints, had almost magical powers.

The custom arose of placing at least one of these objects in the altar of every church.

The more important the relic, the more important the church was considered.

Charlemagne got the cloak that St. Martin – supposedly – had thrown to the beggar as a relic for his palace church, and so the church became know as the Capella – and hence the word “chapel.”

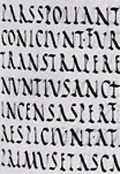

Roman ‘Rustic’ – capitals with a few flourishes

PS: A word on spelling:

“This spelling [miniscule] was first recorded at the end of the 19th century (minuscule dates back to 1705), but it did not begin to appear frequently in edited prose until the 1940s.

Its increasingly common use parallels the increasingly common use of the word itself, especially as an adjective meaning `very small.’ ”

– Merriam-Webster, Dictionary of English Usage (1989)

Risen or Risible? – eBook

Crucifixion of the Christ – eBook