The Invincible Mithras

For almost four centuries Christianity contended with a rival cult that, like the faith of Christ, came from the east, had as its central drama a tale of sacrifice and redemption, and organised its devotees into congregations led by fathers who instructed the faithful and officiated at its ceremonies.

Archaeology draws a blank at the discovery of Christian churches from this embattled era yet mithraea, the small chapels of the Mithraists, dating from the early centuries of the common era, have emerged everywhere from the sands of Iraq to the windswept hills of northern Britain. Christianity did not emerge in the 1st century AD but the Roman form of Mithraism did. In many instances, the earliest Christian churches were built upon the very ruins of the chapels of the vanquished rival.

There can be no doubt about which cult came first – and which enthusiasm ultimately prevailed.

Christ and Mithras – Common ancestry, different temperament

“When Mithraism is compared with Christianity, there are surprisingly many points of similarity. Of all the mystery cults Mithraism was the greatest competitor of Christianity. The cause for struggle between these two religions was that they had so many traditions, practices and ideas that were similar and in some cases identical.”

– Dr Martin Luther King, A Study of Mithraism“, p222.

Christians apologists resent bitterly any suggestion that their faith has less to do with a unique, visiting deity, sent down from heaven, and rather more to do with syncretic borrowings from pre-existing cults and enthusiasms. Yet all human accomplishment builds on what has gone before and religious devotion is no exception.

It is no longer fashionable to regard the Roman cult of Mithras as simply an import from Persia (deriving, earlier still, from India). Scholarly opinion now gives more emphasis to Rome’s own contribution to the “mystery religion” which first appeared in the Roman world in the 1st century AD and spread rapidly during the 2nd century. Yet even on this view, some tentative link to Mithra, the avenging angel of Persia and Mitra, Hinduism’s guardian deity of moral law, is granted.

Wherever it migrated, Mithraism sought an accommodation with other cults, honouring a variety of other deities within its own chapels and often sharing a temple where it had no shrine of its own. In the London mithraeum, for example, images of Serapis, Mercury and Minerva were found. At the mithraeum of Santa Maria, Capua, Eros and Psyche were honoured. Elsewhere, Dionysus and Silenus have been found. Yet Mithraism’s syncretic and democratic character proved to be a fatal weakness in the face of a fiercely intolerant and authoritarian rival.

In stark contrast to Mithraism, Christianity inherited from Judaism a fierce hatred of all other creeds, the mind-set that would in future centuries lead so easily to persecution, pogrom, witch burnings and inquisition.

Mithraism was proscribed and outlawed by the edicts of the Christian emperor Theodosius in the closing decade of the 4th century. Along with its art and architecture, Mithraism’s holy books were destroyed, a loss compounded by the fact that, as a “mystery religion”, the adepts of Mithraism were sworn to secrecy. Fortunately, today we can assemble the myriad small pieces of the puzzle to form a comprehensive, if tentative, picture of the vanished religion. From what emerges, we can see why orthodox Christianity became the implacable foe of the faith that had a very similar story to tell and had been telling it for a great deal longer.

Distribution of Mithraea (1st – 4th centuries)

“The scattering of mithraea, thus identified across the Roman Empire, is perhaps more informative about the cult’s spread and social composition than are the material remains of any of its peers, early Christianity included.” – Roger Beck

Map: Our Common Sun

Compare this extant evidence of the chapels of Mithraism with the often conjectured but unsubstantiated “growth of the church” (see map here).

Across what was once the Roman world more than four hundred mithraea have been identified. Many are sited within the frontier zones of the empire, in northern Britain, eastern Gaul, along the banks of the Danube and the Euphrates. But others are in cities far from the frontier – Rome, Aquileia, Carthage, London among them – or in ports like Ostia and Ceasarea.

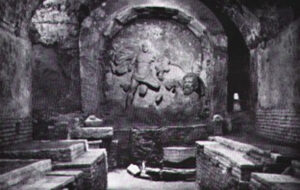

The places of Mithraic worship were never grandiose temples in the style consecrated to other gods. The earliest mithraic chapels were converted caves. Where no suitable cave was available they were typically constructed at least partially underground and without windows, small shrines never able to accommodate more than a couple of dozen members. Many mithraea have survived rather well, despite the ravages of Christians and time. Indeed, many buried by a church built on the same spot have been preserved by the later structure.

Mithraeum of Santa Maria Capua Vetere (“old Capua”), Italy, early 2nd century).

Red and blue stars decorated the vault (symbolizing the heavens).

The earliest mithraea, as here at Santa Prisca, Rome (CIMRM 250), were fully enclosed, and at least partly underground.

Mithraeum below the church of San Clemente, Rome (3rd century).

Mithraeum Ostia Antica. The port of Rome had many mithraea.

A long way from Persia – Mithraeum, London, when first discovered in 1954.

At the other end of the empire, a mithraeum at Dura Europos on the middle Euphrates.

Origins of Mithras

According to the Rigveda, one of foundational texts of Hinduism, Mitra was prominent among a group of Indian solar deities (devas) born to Aditi, the mother of the gods or “cosmic cow”. Mitra, a god of light, was often associated with a sibling sky (night or moon) god Varuna. This dual-god maintained the social and cosmic order by acting as the guardian of truth, oaths and agreements.

A western branch of the Indo-Iranian peoples, migrating into Persia, developed the ancient gods in their own fashion. By the 6th century BC, in the scriptures of Zoroastrianism (the Avesta), Mitra appears as Mithra, the “Lord of wide pastures“, a guardian of cattle and protector of life-giving waters.

But Mithra was now an agent of a supreme creator god Ahura Mazda (aka Ormuzd, or simply Mazda). In a cosmic struggle between good and evil, the “good spirit” Spenta Mainyu stands in opposition to the force of malevolence and chaos Angra Mainyu (aka Ahriman). Mithras, in his role as an all-seeing, ever-vigilant protector (or Yazad) on behalf of Ahura Mazda actively resists the powers of darkness and restores cosmic harmony.

From the Iranian heartland, adoration of Mithra spread northwestward, across Armenia, Pontus and Anatolia, and southwestward, into Syria and the Levant. During the Achaemenid era (6th – 4th centuries BC) Persian armies carried their gods as far as Thrace and the Aegean. In the conquered Greek cities, of Asia Minor, Mithra was identified by the Greeks with own sun god Helios (and later, Apollo) and Greek artistry gave the cult of Mithra a distinctive and attractive visual form.

Westward migration

In the emergent Persian/Hellenistic kingdoms that arose across the region in the wake of Alexander’s conquest of the Persian empire, the magi retained influence in the royal courts and it was Mithra (rather than Ahura Mazda) that became the guarantor of kingly authority and prowess in battle. Throughout western Asian, many generations of kings bore the name Mithradates (“gift of Mithra”) – Parthia, Pontus, Media Atropatene, Commagne, Bosporus, Armenia, and Iberia among them.

Mithra in Commagne

(Above right) On his tomb at Nemrut Dag king Antiochus I of Commagne, son of Mithridates I, greets a god from Persia – Mithra. As his devotees moved westward, Mithra was conflated with Apollo, the Greek sun god, as inscriptions on the statues at Nemrut Dag attest.

At a later stage, the kingdoms of Osroene and Armenia would be among the first to adopt a rival but similar god – Christ.

The Lion of Commagne (2nd – 1st century BC)

Commagne was a short-lived Hellenized Armenian kingdom between the Taurus mountains and the Euphrates, one of the states to emerge from the waning Seleucid empire. In the 1st century BC, the worship of Mithra achieved preeminence and was closely associated with dynastic power and a divinely ordained order. Here the mountain top ruins of a royal sanctuary at Nemrut Dag are extant proof of Greek/Persian religious syncretism. Not only was the king identified with Mithra but with lion images also – symbolic of his political and military power. Thus Antiochus of Commagne is to be seen portrayed as the conquering lion, wearing a lion-embroidered tiara, and seated on a lion-carved throne.

Additional endorsement from heaven is to be found in representations of the constellation of Leo. On an extant carving, a star chart has been imposed upon the image of a lion: three stars above its back are identified cryptically (in Greek) as Mars, Mercury, and Jupiter. A crescent moon hangs around the lion’s neck. Many of these symbols reemerged in later Roman Mithraism – the lion-headed Aion (or Zervan), Luna, Mercury and Mars among them.

Attempts to date the Nemrug Dag “star map” range from 109 BC to 72 AD. But in any event, the purpose of the motif is clear: to identify the royal personage – either Antiochus or his father Mithridates – with divine lordship. In this, we have an early example of the use of religious devotions to achieve political ends: unification of his multi-ethnic kingdom and sanctifying dynastic authority. This smart stratagem would reverberate down the centuries, to Constantine and beyond.

Commagne enjoyed a brief autonomy (162 BC – 72 AD) before being absorbed into the Roman empire.

The Lion of Commagne. The Lion (Leo) was also a grade within the mithraic mysteries.

The lion appears in some mithraic Tauroctonous, as here, crouching (Osterburken). Elsewhere, the lion-headed Aion/ Zervan (right) appears as a statue.

1st century BC – The Lion King of Pontus and the “pirates” of Cilicia

Traditional hostility with Persia did not favour Rome adopting a religion of its enemies. This changed, however, when the army of the east waged a twenty-five year struggle with an enemy protected by a fierce but noble deity, Mithra, which the Roman forces found worshipped throughout west Asia.

Pontus emerged from the northern provinces of Cappadocia during the wars of Alexander’s successors. Its early kings annexed territory of neighbouring states and along the coasts of the Black Sea, eventually to include the Bosporan kingdom of the Crimea. Pontus became a powerful maritime empire and a formidable opponent of Rome.

Early in the 1st century BC, Mithridates Eupator Dionysius, together with his younger brother Mithridates Chrestus, inherited the throne of Pontus while both were still minors. Around the age of twenty, Mithridates eliminated his mother, the regent, and his brother, to become sole ruler of the kingdom, ruling as Mithridates VI. For the next twenty-five years (88 to 63 BC) he would be Rome’s most implacable enemy in the eastern Mediterranean.

Cilicia, on the southeastern shores of Anatolia, had been, nominally, a Roman province from 102 BC but the Roman presence remained confined to a few enclaves along the coast until the time of Trajan. Native rulers allied themselves with Mithridates of Pontus in opposing Roman expansion, particularly in the sea lanes vital both to Rome and themselves. The Romans disparaged them as “pirates” but the problem was severe:

“Supported by its bellicose religion, this republic of adventurers dared to dispute the supremacy of the seas with the Roman colossus.”

– Cumont, The Mysteries of Mithra, p31.

Elements of Pontic armies and fleets gathered in Cilicia with the “pirates”, and over several years they threatened Roman shipping and in particular, the imperial corn supply. Running freely not only in the eastern Mediterranean but also in the western, they allied themselves with rebel Roman forces in Spain. The “pirates” at their zenith reputedly commanded more than a thousand ships and held over four hundred cities and were able to raid the coasts of Italy as far as the port of Ostia, and penetrated far into Greece. Evidently, they introduced the god Mithras into Olympia:

“They offered strange sacrifices of their own at Olympius, where they celebrated secret rites or mysteries, among which were those of Mithras. These Mithraic rites, first celebrated by the pirates, are still celebrated today.”

– Plutarch of Chaeronea, Life of Pompey, 24.1-8. (The Ancient Mysteries, A Sourcebook, Ed. M. W. Meyer).

In this crisis, so worried was the Roman senate that it gave Pompey almost unlimited resources to eradicate the problem. In 68 BC, with more than one hundred and twenty thousand troops and five hundred ships at his disposal, he “cleared the seas of pirates” in little more than four months. It was a prelude to a final confrontation with Mithridates, now allied with Armenia. Pompey’s campaign in the east (66-61 BC), which took him deep into the Caucasus and as far south as Nabatea, won him eternal fame. Mithradates himself committed suicide in the Crimea. The capture of the Jewish prince Aristobulus after a three-month siege of Jerusalem brought Pompey’s dazzling campaign to an end.

The defeated Asiatic Greeks were absorbed into several new provinces. The booty returned to Rome was colossal. Taken to Rome in triumph, along with immense treasure and captured chieftains, was the god Mithras. The formidable deity had won the respect and reverence of the Roman military. Rome assimilated the gods as well as the peoples it conquered and the legionnaires, in particular, had taken to the machismo “Persian” faith, with its ceremonies of male-bonding, self-control, and triumph over death. For a century or more, the history of Roman Mithraism is obscure but we next hear of the cult during the time of Nero, and the pageant of a priest-king of Mithra.

Finding Mithras a face

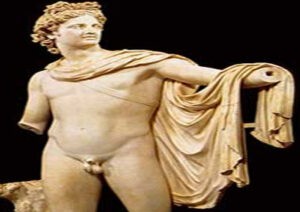

Greek artistry gave dynamic and iconic form to the god from Asia. The earliest tauroctony (bull-slaying) was probably sculpted at Pergamon where the face of Mithras took on more than a passing similarity to the young Alexander.

Greek iconography also gave Mithras a Phrygian cap, like that worn by Attis; a cloak, like that of Apollo; and like Helios, Mithras rode in a fiery chariot across the sky.

Alexander the Great as a young prince

(Athens)

Mithras, a youthful god

(Arles)

Attis, a god of Phrygian origin and, like Mithras, often shown wearing the Phrygian cap.

Mithras Goes to Rome

“A man of noble birth went to a distant country to have himself appointed king and then to return.” – Luke 19.12.

Armenia formed a high plateau and was a natural buffer state between the Parthian and Roman worlds. In Pompey’s settlement of the east, Tigranes II had been allowed to continue as king of a reduced Armenia, but both Rome and Parthia competed for control of the kingdom. First Antony (with his infant son Alexander Helios) and then Augustus, through a succession of Roman nominees, imposed Roman control in Armenia. But at opportune moments, Parthia installed its own client kings (Arsaces, Orodes). In 35 AD, Rome toppled Arsaces and installed Mithridates of Iberia (modern Georgia). For the next fifteen years Parthia accepted the Roman protectorate of Armenia.

But in 53 the Parthian king Vologeses placed his brother Tiridates on the Armenian throne. The Roman response came five years later when Nero’s general Corbulo led an invasion of Parthia. The conflict proved indecisive and was resolved by a famous compromise: the Parthian prince installed as king of Armenia would retain the throne but would receive his crown from the hands of the Roman emperor. That prince was Tiridates, a priest of Mithra.

“Tiridates presented himself in Rome … [his] progress all the way from the Euphrates was like a triumphal procession. and his whole retinue of servants together with all his royal paraphernalia accompanied him. Three thousand Parthian horsemen and numerous Romans besides followed in his train … for the nine months occupied in their journey… Nero took him up to Rome and set the diadem upon his head… These were his words: “Master, I am the descendant of Arsaces, brother of the kings Vologaesus and Pacorus, and your slave. And I have come to you, my god, to worship you as I do Mithras. The destiny you spin shall be mine; for you are my Fortune and my Fate.”

– Cassius Dio, Roman History, 62.73.

Nero (and the whole of Rome) were enthralled by this massive embassy from the east which reached the city by an overland route in May 66. Apparently, Nero was fascinated by the Parthian priest-king and was initiated by him into the religion of Zoroaster and Mithra. Perhaps his head was turned by the obeisance. At the theatre of Pompey, on the Golden Day, a massive purple canopy showed Nero driving the chariot of the sun among the stars, much like Mithras. On his coinage Nero adopted the radiant crown as the symbol of his splendour. Was the Roman emperor, among other things, an incarnation of Mithras?

A dupondius from the year 66, minted at Rome. Nero wears a radiate crown. The reverse shows the Temple of Janus with closed doors, signifying “peace with Parthia”.

Adaptation of Mithras for Roman taste

“If the growth of Christianity had been stopped by some fatal disease, the world would have been Mithraic.“

– Ernest Renan, Marc-Aurèle et la fin du monde antique.

Worship of the Sun, along with the Moon and the Evening Star, had great antiquity in Rome, perhaps from as early as the Sabine kings. Sol Indiges had his temples, even if his position within the pantheon was obscure. Augustus consecrated stolen Egyptian obelisks to the Sun god and popular legend credited that deity for a decisive victory of Vespasian over Vitellius in 69.

Into this world, imported by soldiers, merchants and oriental slaves, was Mithras, at first a rival for the old sun god but in time, allied to and then conflated with, ancient Sol. Both Mithras and Sol enjoyed the epithet Invictus (Unconquerable) and in time, a single deity emerged – Mithras Sol Invictus. Among the Greeks, reference was made to the Great God Helios-Mithras. The god from the east, in the course of a few decades, climbed the social order, to become an enthusiasm of state officials and of the emperors themselves.

The teenage emperor Elagabalus (218-222), a “religious reformer” one hundred years before Constantine, imported into Rome from his native Syria the stone which hosted his own version of the sun god, Elagabalus (Helio’gabalus to the Greeks), and housed it in a massive temple next to the Palatine palace. Daily, a hundred bulls were sacrificed on its many altars. The emperor’s intent, cut short by assassination, was a solar monotheism. That idea returned with new vigour fifty years later with Aurelian (an emperor whose very name connoted some ancestral connection with the sun) and who, after his war with Zenobia, restored the Temple of the Sun in Palmyra and built another in Rome itself.

The late 3rd century was characterised by an ascendancy of sun god worship in various forms. Diocletian favoured Mithras, having identified himself at an earlier point with Jove. A crisis of succession in 308, after Severus was killed, prompted the retired Diocletian to convene a conference of the Augusti at the Danubian fortress town of Carnuntum. Besides the election of Licinius, the temple of Mithras in the city was enlarged into a state cult centre and Mithras was proclaimed fautor imperi sui (“Protector of the empire“). At this stage, the renegade Constantine, skulking in Trier, opted for his own version of the sun god – Apollo.

Aurelian’s coinage had celebrated his affinity with the sun god, and his example was followed by his successors down to – and including – Constantine himself. Constantine’s “apostate” nephew Julian, last of the pagan emperor, was initiated into the Mysteries of Mithras around the year 360. Both a public cult of the sun and an esoteric cult of Mithras coexisted until the prohibitions of Christianity.

The sun, under whatever name (including Jesus Christ!) would protect and legitimized the rule of emperors – and all future kings.

Christian hostility – “Mithraism is foreign Devil Worship!”

Who would defend Mithras?

For all of its imperial connections and popularity throughout the empire, Mithraism lacked a professional clergy.

In the 4th century the militant Christian writer Firmicus Maternus exhorted the sons of Constantine to eradicate paganism. His attack on the rival cult of Mithras, so similar in many respects to his own cult of Christ, made a crass appeal to Roman patriotism, denigrating Mithraism as a squalid “Persian” import.

“Their sponsor, the Devil … The male they worship a cattle rustler … Him they call Mithra, and his cult they carry on in hidden caves, so that they may be forever plunged in the gloomy squalor of darkness and shun the grace of light …

So you who declare it proper for the cult of the Magi to be carried on by the Persian rite in these cave temples … think it worthy of the Roman name to serve the cult of the Persians ...”

– Firmicus Maternus, The Error of Pagan Religions, 5.1-2.

Another Christian luminary, Jerome, noted in his correspondence, how a Roman aristocrat won his Christian credentials by wholesale destruction of a Mithraic chapel.

” … did not your own kinsman Gracchus, whose name betokens his patrician origin, when a few years back he held the prefecture of the City, overthrow, break in pieces, and set on fire the grotto of Mithras and all the dreadful images therein?

Those I mean by which the worshippers were initiated as Raven, Bridegroom, Soldier, Lion, Persian, Sun-Runner, and Father? Did he not send them before him as hostages, to obtain for himself Christian baptism? “

– Jerome, Letter to Laeta.

Whether by rampaging converts, the extreme destructiveness of “gangs of black-robed monks” or mere neglect, the numerous temples of Mithras fell into ruin. Christianity began as it intended to go on – with a brutal intolerance of all who refused to bend the knee to gentle Jesus and his earthly henchmen. It held a special vehemence towards a cult that in many respects had the same story to tell – and had been telling that story for a great deal longer.

Sources:

Malachi Martin, The Decline & Fall of the Roman Church (Secker & Warburg, 1981)

Kevin Butcher, Roman Syria & the Near East (British Museum, 2003)

Michael Parenti, History as Mystery (City Lights, 1999)

John G. Jackson, Christianity Before Christ (American Atheist Press, 1985)

S. Angus, The Mystery Religions (Kessinger Publishing, 2003)

Antonia Tripolitis, Religions of the Hellenistic Roman Age (Eerdmans,2002)

David Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries: Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World (OUP, 1991)(link)

Everett Ferguson, Backgrounds of Early Christianity (Eerdmans, 2003)

Franz Cumont, The Mysteries of Mithra (1896, 1899)

Engelbert Winter, “Mithraism & Christianity in Late Antiquity”, Ethnicity & Culture in Late Antiquity (Duckworth, 2000)

Manfred Clauss, The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries

Roger Beck, The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire: Mysteries of the Unconquered Sun (OUP, 2007)

Roger Beck, “The Mysteries of Mithras: A New Account of their Genesis”, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. LXXXVIII, (1998)

Roger Beck. Beck on Mithraism (Ashgate, 2004).

G. R. S. Mead, The Mysteries of Mithra (Theosophical Publishing Society, 1907)

M. J. Vermaseren, Corpus inscriptionum et monumentorum religionis mithriacae (2 vols., Martinus Nijhoff, 1956, 1960)

Porphyry, De astro nymphorum (On the cave of the nymphs)

History Hunters

Mithraeum. Our Common Sun

The names Mitra – Mithra – Mithras derive from the Indo-European root “mihr,” a contract. Here was the germ for a god that personified agreement and just order.

India

The god Varuna was often paired with Mitra, the former aspect of the god ruling the night and the latter aspect ruling the day,

(Bhubaneswar, Orissa)

Persia

Dar-i-Mihr – “court of Mithra”. Persian Fire Temple from the Achaemenid era.

In ancient Persia contracts were sworn before fires so that they might be made in the presence of Mithra.

With the emergence of Zoroastrianism, Mithra gained an important but subordinate role to the higher god Ahura Mazda.

For Zoroastrians the sun was the eye of Mithra.

Mithras in Persia

Mithra (left) attends the investiture of Ardashir II (centre). Authority is bestowed on the Sassanid king of Persia (379 to 383) by the supreme deity Ahura Mazda.

Mithra in Pontus

In the Hellenistic kingdom of Pontus, bordering the Black Sea, Mithra was assimilated to the lunar god Men and was mounted on horseback.

This example is actually from Neuenheim, Heidelberg (southwest Germany). Notice that Mithras is accompanied by a serpent and a lion. CIMRM 1289

Mithras in Illyricum

Mithraeum in Močići, south of Dubrovnik, Croatia.

The earliest mithraic chapels were converted caves. In this example, the tauroctony is carved into the living rock above the cave entrance.

Mithras in Commagne

This Hellenised Asiatic kingdom did much to identify dynastic power with the divine majesty of Mithra. At Nemrug Dag (in today’s southwest Turkey) an impressive mountaintop statuary still marks the adoption of Mithra by the ruling family.

Apollo lends Mithras his cloak

A naked Apollo wears the cloak (chlamys), adapted for the iconography of Mithras.

(2nd century copy of 4th century BC bronze, Vatican. ).

Originally the figure of Apollo held a bow and the god slew the Python, the primordial serpent guarding Delphi, just as Mithras slew the primordial bull.

The Lion King

Mithridates VI of Pontus (Louvre), the Roman republic’s most formidable and tenacious enemy.

In a 25-year struggle, residual elements of the defeated Greek forces gathered with their allies in Cilicia and continued to harass Roman shipping and raid coastal cities.

Roman client-kings of Armenia

Tigranes III, IV, V, Ariobarzanes II, Vonones, Zeno-Artaxias III.

Mithras in Rome

‘Alcimus, slave-bailiff of Tiberius Claudius Livianus, gave the gift to the sun-god Mithras in fulfillment of a vow.’

(Rome 2nd century)

When the Romans first encountered the cult of Mithra during Pompey’s campaign in the east, the god’s devotions had evolved over several centuries and had been influenced by Zoroastrianism and the religion of Persia.

Rome’s Mithraea

At least three dozen Mithraic sanctuaries are known in Rome alone.

Mithraeum of the Circus Maximus

The five-room structure (discovered in 1931) was converted for cult use in the second half of the 3rd century.

Mithraeum under the Barberini Palace

Mithraeum under the church of Santo Stefano Rotondo

Revealed below the 5th century church was part of a mid-2nd century barrack block (the Castra Peregrinorum). Part of the barrack block was itself discovered to have been converted to Mithraic use about 180 AD.

Mithras – Helios

Helios the sun-god from the time of Aurelian (270 -275).

Compare this image to “JC in the Sky” from the same period.

Mithras was proclaimed the principal patron of the empire by Aurelian in 274. On December 25th he dedicated a temple to the sun-god in the Campus Martius.

Diocletian honours Mithras, Protector of the Empire, in the Forum at Rome

Column base, Roman Forum. It is a scene of imperial sacrifice which has been heavily defaced.

Close examination reveals that above the goddess Roma is the radiate head of Mithras.

Diocletian and Galerius have been effaced.

American Journal of Archaeology

“For the Salvation of our lords the four emperors and the noble Caesar, and to the god Mithras, the Invincible Sun from the east to the west.”

An inscription from the mithraeum in London, dated to 307–310.

Resistance is futile

The Magi attend the birth of Jesus. Their “Adoration” symbolizes the submission of Mithraism to triumphant Christianity.

(From 6th century Thessaly, British Museum)

Theodosius made worship of Mithras punishable by death. The god had fallen.

The imagery and iconography of Mithras were expropriated wholesale by the more aggressive and favoured cult of Christ.

On to the head of Jesus fell Mithras’s sun disc. Christian bishops assumed his headdress and mitre.