End of Classic Scholarship in Egypt

The Real Barbarians

“The monks, who rushed with tumultuous fury from the desert, distinguished themselves by their zeal and diligence … In almost every province of the Roman world, an army of fanatics, without authority and without discipline, invaded the peaceful inhabitants; and the ruin of the fairest structures of antiquity still displays the ravages of those barbarians who alone had time and inclination to execute such laborious destruction.“

– Gibbon (Decline & Fall of the Roman Empire, chapter 28)

Roman Egypt: Jewel in the Crown

The conquest of Egypt in 30 BC rewarded the caesars with a lavish prize – yet also considerable danger. Egypt was a source of immense accumulated wealth and exotic wonder but the relative ease with which this ancient land could be defended – and its strategic control of much of Rome’s grain supply – made the province an ideal base from which to mount a bid for the throne. Vespasian in the troubled year of 68 had camped in Egypt, awaiting news from Rome. When Valerian was captured on the Persian front in 260 first the ‘Macriani’ usurpers and then Mussius Aemilianus had been hailed in Egypt. After the defection of the Kingdom of Palmyra in 273, Aurelian had faced a revolt in Alexandria. In 281, Julius Saturninus, a commander in Syria, was another who had been encouraged by the Alexandrians to seize power in the east (though soon after his bid he was assassinated). A serious rebellion led by Domitus Domitianus and Aurelius Achilleus in 296/298 had required Diocletian’s personal intervention.

In anticipation of such dangers, Augustus had placed Egypt directly under his personal authority and no senator could even step foot in the province without his express approval. The treasury of the Ptolemies became the basis of Augustus’s personal fortune.

The Conflicts of Alexandria

Unlike the forested lands of Gaul and Germany, in Egypt were cities that pre-dated the foundation of Rome by millennia. Demographically the province was divided between a sophisticated and urban ‘foreign’ element – mainly Greek and Jew – and the stubborn and superstitious native Egyptians. Within the many cities – and especially within Alexandria itself – cultural and commercial rivalry often brought the Greeks and Jews into conflict. Feuds, riots, and massacres were not infrequent.

The Romans were a pious people but in Egypt they faced religion on an epic scale. A rich and powerful caste of priests, unlike anything known in Rome, had historically been close to imperial power and still wove a spell from a vast array of fortress-like temples. Priestcraft, and the whole paraphernalia of temple commerce, thrived, even though, with the passing of the last of Ptolemies, they had lost their god-king.

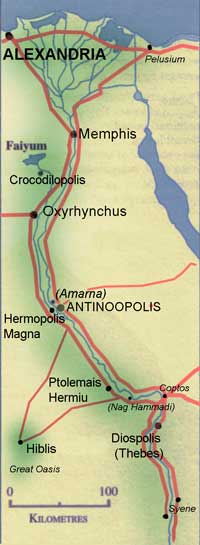

In the main, the Egyptians were an under-class of rural labourers, alienated from the ‘foreign landlords’, occupying the cities. As a food source, the soil of the Nile Valley and the Faiyum oasis were amazingly fertile – a ten per cent grain levy was sufficient to feed Rome for four months of the year – but the producers saw little benefit.

With the transfer of power from Greeks to Romans the cycle of life appeared unchanging – but beneath the surface boiled a complex brew.

Oxyrhynchus, named for the ‘sharp-nosed fish’ (the sturgeon) which the city held sacred. According to legend, this fish ate the phallus of Osiris when the god’s body was cut into pieces by his brother Seth. Isis, as ‘Abtu, Great Fish of the Abyss,’ was identified with the penis-swallower. The fish cult spread to many parts of Egypt.

During Roman times, Oxyrhynchus became a large and sophisticated town (the third city of Egypt), controlling access to the western oases.

The city had about twenty pagan temples but by the 4th century Oxyrhynchus had become a hotbed of Christianity. Rufinus reported 12 churches as of the early 5th century (and added that the local bishop told him of ‘the presence of 10,000 monks and 20,000 nuns’!) A papyrus dated to 535 gives a figure of some 40 churches for the city.

A revolt in Oxyrhynchus against the Arabs in 645/6, which also effected Alexandria, was ruthlessly suppressed. The site of Oxyrhynchus appears to have remained desolate until resettled (under the name ‘Bahnasa’) by Arabs in the 9th century.

The early medieval Arabic epic ‘Kitab Futuh al-Bahnasa al Gharra’ (‘The Conquest of Bahnasa, The Blessed’) by Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Mu’izz, recounts the notion from Matthew’s Gospel that the holy family had ‘fled to Egypt’, saying that they stayed at Oxyrhynchus.

Many papyri dating from 3rd – 8th centuries were discovered in the town’s rubbish mounds between 1896 and 1906.

Along with classics from Greek literature were fragments of Christian texts, included a collection of ‘Logia’ – sayings of Christ – which do not appear in the gospels.

Something Fishy Here!

con of the Oxyrhynchus fish cult (complete with the horns of Hathor and sun disc of Ra).

Could it possibly have any connection with this … Sign of the Fish?!

Christian catacomb motif

(St Domitilla, early 4th century)

Roman Egypt

Wealth & Discord

Alexandria, second city of the Roman world, built on a spit of land unaffected by Nile floods between Lake Mareotis (Mariout) and the Mediterranean.

Under its Greek kings, the Ptolemies, Alexandria accumulated wealth and culture in equal measure. Serving as Europe’s port for trade with India, Arabia and Africa, and itself a manufacturing centre for papyrus, glass and linen, the city became the richest, most powerful metropolis of the Orient.

Wealth brought leisure, and leisure, in turn, the arts. Schools of philosophy and science and diverse cults flourished. The city was home to not one but at least three libraries.

The grain levy on Egypt passed through the port to feed first Rome and then Constantinople. From the 4th century onwards the rise of Constantinople challenged (and eventually supplanted) Alexandria’s preeminence. The commercial rivalry was reflected in ferocious ‘theological’ disputes.

With the triumph of Christian fanaticism early in the 5th century the city went into terminal decline.

Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt, founded around 3,100 BC, at a site where it could control the land and water routes between Upper Egypt and the Delta.

When the Greeks arrived and moved the capital to Alexandria, Memphis suffered. The city remained important in Roman times but with the event of Christianity the association of Memphis with traditional Egyptian religion meant further decline. The city became a shadow of its former greatness.

The final demise of Memphis probably occurred with the invasion of Muslim conquerors in 641 when they established a new capital a short distance north of the city at Fustat (Cairo).

Antinoopolis, the only Roman ‘new town’ in Egypt. A city founded specifically to honour the cult of Antinous, by the 3rd century the city actually had two rival Christian bishops! To give Antinoopolis a viable economy Hadrian linked the town with the Red Sea trade routes. Greek settlers here were allowed to marry Egyptian natives – an unprecedented innovation.

Ptolemais, the only Greek ‘new town’ of the interior. Founded by Ptolemy Soter it supplanted Thebes as the capital of Thebais and became as important as Memphis. Ptolemais was an important lading-place for the corn-produce of Middle Egypt. A cult in the city honoured the Ptolemys.

Civil Power versus Church Power

Augustus and his successors placed Alexandria under the rule of a Roman Prefect, or Governor, drawn from the equestrian rather than the senatorial class, an official who administered the province through mainly Greek civil servants. This had worked well but with the inauguration of a “Christian Monarchy” a second hierarchy of officials appeared, in conflict with the first.

Before the “Constantinian Revolution” it had been the policy of Rome to exercise great tolerance in religious matters, indeed to have little regard for popular superstitions. But from the 4th century onward, unorthodox thought became a crime and a burgeoning Church hierarchy, headed by a bishop, policed popular sentiments.

The duopoly meant that neither the Bishop nor the Prefect could unseat each other – both derived their power from the Emperor. But inevitably personalities came into conflict. In the early years of the 5th century these personalities were an urbane and educated pagan prefect called Orestes and an ambitious and fanatical bishop called Cyril. It was a clash between the classic liberality of antiquity and the vulgar intolerance of the New World Order of Christianity.

Enter Cyril, “the Proud Pharaoh”

That lion of lynch mob justice, Bishop Theophilus (“a bold, bad man, whose hands were alternatively polluted with gold and with blood” – Gibbon, chapter 28), who had led the rampage against the Alexandrian Temple of Serapis in 371, died in 412. In typical Christian fashion a violent ‘crisis of succession’ followed his death. One contender was the Archdeacon Timotheus who rather usefully had the support of Abundantius the military commander. But he had not reckoned with the determination of Theophilus’s nephew Cyril, a fanatic recalled from the desert.

Cyril had been indoctrinated from boyhood in the monastery of Saint Macari, where his head had been filled with the fierce intolerance of the ‘Desert Fathers.’ After three days of wrangling and intimidation, Cyril grabbed the Archiepiscopal Chair, and so became “the 24th Pope of the See of Saint Mark”. Among his various descriptive titles was ‘Pillar of the Faith.’‘ He was 36 years old. For the next 31 years he would be boss of bosses in Alexandria.

Cyril began his reign the way he meant to go on – by persecuting his opponents.

Cyril eyed enviously the wealth of the Novatians, an established Christian sect in the city. The Novatians were early-day ‘puritans’, opposed to the loose ways of the orthodox hierarchy and so named for a 3rd century ‘anti-pope’ who had himself lost out in a power struggle in Rome. Gibbon describes them as ‘the most innocent and harmless of sectaries.’

Their doctrine was too ‘intellectual’ to gain Cyril’s support, and among the primate’s first acts was the closure of Novatian churches and the seizure of their sacred vessels and ornaments.

Having purged the official Church of Alexandria of its dissenting minority, Cyril next targeted the Jews. This numerous community, he decided, should be expelled from the city and the privileges which they had enjoyed for seven hundred years, since the time of Alexander the Great, rescinded.

“Without any legal sentence, without any royal mandate, the patriarch, at the dawn of day, led a seditious multitude to the attack of the synagogues. Unarmed and unprepared, the Jews were incapable of resistance; their houses of prayer were levelled with the ground, and the episcopal warrior, after rewarding his troops with the plunder of their goods, expelled from the city the remnant of the unbelieving nation.”

– Gibbon (Decline & Fall, chapter 47)

Thus did Alexandria lose a wealthy and industrious colony.

Orestes Outflanked by the Ambitious Prelate

Inevitably, the militant bishop clashed with the secular authorities and, in particular, with Orestes the Prefect. Orestes saw no sense in the attack upon the Jews and the consequential civil commotion. Unable to over-rule the bishop, the governor complained to the child emperor Theodosius II (408 – 450). The Bishop, he pleaded, was usurping the functions of his administration, even of the police. His appeal was in vain. The teenage Theodosius was completely under the dominating influence of his sanctimonious sister the Regent Empress Pulcheria. Pulcheria was a pious ‘Christian virgin’ of twenty two who was busily waging her own campaign for Christ by turning the imperial palace into a virtual monastery.

Far from censoring Cyril, the Bishop was invested by the Empress with coercive power, effectively fusing Church and State in the province of Egypt. In gratitude Cyril likened the silly girl to the Blessed Virgin herself (“De fide ad Pulcheriam”).

Cyril moved on to the attack. The anti-intellectual prelate demonized traditional Alexandrian learning and science as perfidious paganism. The hated Orestes himself was accused of being under the spell of sorcery and the ‘Republic of Plato’. Orestes publicly demonstrated his ‘treason’ by attending lectures at the Neoplatonist School of Philosophy. The governor’s defence was an appeal to the traditional policy of the caesars, which had always been one of great leniency toward all schools of philosophy. But he spoke for a dying freedom. Several hundred of Cyril’s fanatics, half-starved monks from the monasteries of Nitria, assaulted the Prefect in his chariot, leaving him bloodied and angry. A monk – Ammonius – was executed for the attack but the bishop immediately hailed the assailant as a martyr. A blood sacrifice was now required to appease the henchman of Christ.

Hypatia

“Fables should be taught as fables, myths as myths, and miracles as poetic fancies. To teach superstitions as truths is a most terrible thing. The child-mind accepts and believes them, and only through great pain and perhaps tragedy can he be in after-years relieved of them. In fact, men will fight for a superstition quite as quickly as for a living truth – often more so, since a superstition is so intangible you can not get at it to refute it, but truth is a point of view, and so is changeable.”

– Words attributed to Hypatia, though not, alas, authentic!

A rather different woman to the Empress Pulcheria lived and died in Alexandria. Hypatia was the daughter of Theon, the astronomer, and she inherited her father’s intellectual gifts. Rising to become head of the Neoplatonist School of Philosophy her fame attracted students (including Christian theologians!) from across the Mediterranean – “as many saw her as one of the masters in communication”

Hypatia was much respected by the governor Orestes, who it seems consulted her even on matters of civil administration – “deeming her one of the masters in public administration.”

Cyril was incensed that Hypatia’s reputation and talents were giving the cause of paganism a dangerous prestige, and thereby preventing the ‘progress of the Faith’. It rankled deeply that she enjoyed a close friendship with the prefect, and the scurrilous bishop likened the relationship of Hypatia and Orestes to that of Cleopatra and Mark Antony. ‘If she could,’ he ventured, ‘she would set up an Egyptian Empire!’ From his pulpit Cyril inveighed against the harlot and, in response to his call, more fanatics swarmed in from the desert.

Hypatia

According to the Suda lexicon, Hypatia wrote commentaries on the Arithmetica of Diophantus of Alexandria, on the Conics of Apollonius of Perga, and on the astronomical canon of Ptolemy.

These works are ‘lost’, but their titles, combined with the letters of Synesius of Cyrene (afterward Bishop of Ptolemais) who consulted her about the construction of an astrolabe and a hydroscope, indicate that she devoted herself particularly to astronomy and mathematics.

Of course, she may not have been a virgin and therefore unlike Empress Pulcheria, was not made a saint.

Murder of Hypatia

Hypatia was set upon by the mobsters as she was going in her carriage from her lecture-hall to her home. She was dragged to a nearby church where mob-rule took control. Stripped, beaten and hacked to pieces her dismembered body was burned to hide all traces of the crime.

The year was 415. A distressed Orestes, officially still in charge of the province, ordered the execution of Hierax, a Christian monk, for complicity in the murder but within days Orestes himself was murdered. The triumphant Bishop Cyril let it be known that “Hypatia had gone to Athens”, that there had been no mob, no tragedy and that the prefect had resigned and fled. The expulsion of the Jews continued and the Bishop himself nominated a successor to Orestes. From Pulcheria Cyril elicited a new decree, which raised the number of his personal parabalani mobsters from 500 to 600.

Religious tyranny had enthroned itself in the erstwhile world-capital of intellectualism.

Decline of Alexandria

Following the murder of Hypatia, scholars began to leave the city. Her death marked the beginning of the decline of Alexandria as a major centre of ancient learning, indeed as a city of any consequence at all. The new archbishop purged his realm of the scholars, poets, and philosophers who had built the metropolis and who still cherished a passionate regard for the culture and civilization of the pagan world.

By the Middle Ages, ‘Alexandria’ would occupy little more than the spar of land leading from the city proper to the famous lighthouse.

But thanks to Cyril, dogmatism as a police system reigned supreme. For more than a decade Cyril built up his power base within Alexandria and the lands of Upper Egypt and then he cast his ambitious eyes further a field. His next ‘intellectual’ challenge came from the second city of the east – Antioch.

Conflict with Nestorius: Imperial Politics further elaborates “Christian Theology”

In the year 428, to the consternation of Cyril, Nestorius, a priest-monk of Antioch, became archbishop of Constantinople. Another fanatic, Nestorius greeted Emperor Theodosius with the words:

“O Caesar! Give me the earth purged of heretics, and I will give you the kingdom of heaven. Exterminate with me the heretics, and I will with you exterminate the Persians.”

Best remembered for his ‘Christology’ rather than the murder of Arians and ‘Quartodecimans’ (they made the mistake of using a ‘Jewish’ calendar for Easter), Nestorius identified no fewer than twenty three heretical factions which required corrective punishment. Yet by the reckoning of his opponents, Nestorius and the clergy of his ‘Syrian school’ were themselves abominable heretics, for they taught that Christ was not one but two distinct persons!

According to Nestorius, Christ was two separate entities, one divine and therefore beyond human frailty, and the other human and thus susceptible to all the fragility of the flesh. The divine Christ could neither suffer or die, and therefore, on the cross it was the human Christ who had suffered and died. Nestorius spoke out against calling the Blessed Virgin Mary the ‘Theotokos‘ or ‘Mother of God’, a term that had been in use for some time but was plainly pagan in origin.

From Alexandria, Cyril, resentful of any interference from the ‘Byzantine’ court, strongly contested these views. He expounded the ‘Egyptian’ doctrine of the ‘indivisible union’ of divine and human natures, losing the troubling subtleties of Nestorius in ‘divine mystery.’ Cyril’s own simple ‘logic’ was that if Jesus Christ was God, it followed that his mother was the ‘Mother of God’. He penned a creed on the ‘Incarnation of the Logos’ which in time would become Orthodox Doctrine.

A violent conflict developed similar to that which had engulfed Athanasius and Arius a century earlier, and every bit as acrimonious. A deadly ’12 anathemas’ passed between the protagonists! Cyril appealed for support to the patriarchs of the other eastern churches and directly to Empress Pulcheria. He also solicited the backing of the bishop of Rome, Celestine, a fellow persecutor of dissenters (Novationists, Pelagians). Celestine had no understanding of Greek or theological subtleties but at that time was locked in a power struggle with the North African Church. He jumped at the opportunity to make a ‘ruling’ effecting the eastern churches.

Nestorius gained the support of Theodosius himself, who had taken to calling Cyril ‘the proud pharaoh’. The Emperor summoned a general council to meet in Ephesus in June 431 to settle the affair.

Effete Emperor Knuckles Under

The third general Council was attended by 200 bishops. Cyril presided, attended by fifty Egyptian bishops. He lost no time, convening the council before the Nestorians had arrived and getting Nestorius and the ‘Antiochans’ condemned and excommunicated.

When John of Antioch and several of the ‘Nestorian’ bishops finally reached Ephesus they assembled separately, ‘deposed’ Cyril for heresy and labelled him a ‘monster, born and educated for the destruction of the church.’ In the stalemate, both sides appealed to the Emperor. Cyril and Nestorius were both arrested and kept in confinement and the verdict of the Council annulled. But then three papal legates arrived from Rome, condemned Nestorius, approved Cyril’s conduct, and declared the sentence pronounced against him void.

For three months the mild and perplexed Theodosius held his ground but in Ephesus Cyril’s supporters once again loosed their army of fanatics.

“A crowd of peasants, the slaves of the church, was poured into the city to support with blows and clamours a metaphysical argument… Cyril disembarked a numerous body of mariners, slaves, and fanatics, enlisted with blind obedience under the banner of St. Mark and the mother of God.”

– Gibbon (Decline & Fall, chapter 47)

Cyril escaped back to Egypt but continued to pressurise the emperor with prodigious bribes to his courtiers and a clarion call to the monks of the capital. At their head went a venerable crazy, a hermit named Dalmatius who had not been out of his cell for 48 years. The mob besieged Theodosius’s palace, chanting psalms and abuse. The Emperor caved in, vindicated Cyril and ordered an unrepentant Nestorius into exile – in Upper Egypt.

Some years later, encouraged by his exiled wife Eudoxia, the worm turned: Theodosius embraced the cause of ‘monophysitism’ and declared Christ ‘had only one nature and it was divine.’

The Library of Alexandria

There were many great collections of books in the ancient world. Most were open to any scholar from anywhere in the world. None of them survived the Christian Dark Age.

The most famous, of course, was the Library at Alexandria. In fact, there were at least three different libraries coexisting in the city.

The main or ‘Royal Library’ was in the Brucchium (northeast sector of the city), close to the palace grounds and forming part of the Museum, a ‘temple’ dedicated to the nine Muses (in the style of Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, Zeno’s Stoa and the school of Epicurus). The library was surrounded by courtyards, gardens, and a zoo. The gathering of books and scrolls had begun with Ptolemy I Soter (304 – 284 BC) using the Greek scholar/politico Demetrius as his agent. Works were translated into Greek, most famously the Septuagint – Jewish scripture – supposedly the labour 72 rabbis. (Letter of Aristeas, 9 -10 (180 -145 BC) Ptolemy’s ambition had been to possess all known world literature.

Scholars – perhaps as many as a 100 – were invited to residency at the Museum and to analyse critically observations and deductions made in mathematics, medicine, astronomy, and geometry. They were fed and funded initially by the royal family, and later, during the Roman period, by public money. Most of the western world’s discoveries were recorded and debated there for the next 500 years.

The evidence of Plutarch, Gellius and Seneca strongly indicates the Royal Library had suffered considerable fire damage at the time of Julius Caesar’s expedition when Caesar torched the fleet of Cleopatra’s brother and the fire spread to the harbour area.

Plutarch informs us that Mark Anthony, making good the loss, gave Cleopatra the entire contents – some 200,000 rolls – of the rival Pergamon library as a gift.

A ‘daughter Library’ was located in the nearby temple of Serapis in the south-western quarter (Epiphanius of Cyprus (c. 402 AD) Weights and Measures). The Serapeum – in honour of the new god – had begun with Ptolemy II Philadelphus and was completed by his son.

The Emperor Claudius, in the mid-1st century, set up the Claudian Library to be a centre for the study of history. Hadrian, following a visit to Alexandria in 130, restored the city and founded a new library in the Caesareum. Sophists, such as Dionysius of Miletus and Polemon of Laodikeia, where attracted to the city in what was a second century revival of Alexandrian scholarship. This brief flowering ended with the “rapine and cruelty” which Caracalla visited upon the eastern provinces early in the third century.

We may never know precisely the fate of reputedly 400 – 700,000 priceless scrolls. The civil commotions of the 260s and 270s, when much of the city was damaged, would not have been happy days for the libraries.The cutting off of imperial revenue by 4th century Christian Emperors sent the Museum into terminal decline. Writing early in the 5th century, Orosius, Christian author of History against the Pagans, admitted fellow Christians had plundered temples and emptied book chests. Gibbon was in no doubt:

“The valuable library of Alexandria was pillaged or destroyed; and near twenty years afterwards, the appearance of the empty shelves excited the regret and indignation of every spectator whose mind was not totally darkened by religious prejudice.” (Chapter 28).

Gibbon placed the blame squarely at the door of Theophilus. That Bishop Theophilus had led the destruction of pagan temples, most famously the Serapeum, is certain. Socrates Scholasticus reports the following:

“Demolition of the Idolatrous Temples at Alexandria, and the Consequent Conflict between the Pagans and Christians.

At the solicitation of Theophilus bishop of Alexandria the emperor issued an order at this time for the demolition of the heathen temples in that city; commanding also that it should be put in execution under the direction of Theophilus.Seizing this opportunity, Theophilus exerted himself to the utmost … he caused the Mithreum to be cleaned out… Then he destroyed the Serapeum… and he had the phalli of Priapus carried through the midst of the forum. … the heathen temples… were therefore razed to the ground, and the images of their gods molten into pots and other convenient utensils for the use of the Alexandrian church … “

It may well be that that the noble Hypatia was the ‘last member of the Library of Alexandria.’

Sources:

William Dalrymple, From the Holy Mountain (Flamingo. 1998)

Michael Walsh, A Dictionary of Devotions (Burns & Oates, 1993)

Dom Robert Le Gall, Symbols of Catholicism (Editions Assouline, 1997)

Leslie Houlden (Ed.), Judaism & Christianity (Routledge, 1988)

Norman Cantor, The Sacred Chain – A History of the Jews (Harper Collins, 1994)

R. E. Witt, Isis in the Ancient World (John Hopkins UP, 1971)

Alison Roberts, Hathor Rising-The Serpent Power of Ancient Egypt (Northgate, 1995)

Timothy Ware, The Orthodox Church (Penguin, 1993)

Luciano Canfora, The Vanished Library (Hutchinson Radius, 1987)

Edward Gibbon, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

J. B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire (Macmillan, 1923)

Hypatia (370 – 415)

Hypatia, Alexandrian Neoplatonist philosopher and mathematician.

Brutally murdered by a mob of monks agitated by Bishop Cyril and led by Cyril’s right-hand man, Peter the Reader.

Dragged from her chariot and into a church, she was stabbed repeatedly with oyster shells. Her naked body was burned to disguise the crime.

Hypatia was not made a saint, nor honoured as a martyr.

‘Saint’ Cyril, however, made the grade. A ‘Pillar of the Faith’ he was declared a doctor of the Universal Church in 1882. Cyril remains a luminary of the Coptic Christian Church to this day.

Nice one, Cyril.

Mind of a Fanatic – St Cyril

Many of Cyril’s writings are preserved – including Thesauri (an attack on Arius) and ‘On the Mystery of the Trinity’.

Significantly, 80 years after the assassination of Julian, Cyril felt it necessary to write an ‘Apologia in Defence of Christianity against the Emperor Julian the Apostate.’

Poor Julian must have hit the nail right on the head!

Dogmatic to the last, Cyril made it a rule ‘never to advance any doctrine which he had not learnt from the ancient fathers.‘

A liturgy bears his name. Apparently, it “overflows with deep spiritual insight and reverberates the inmost yearnings towards God.”

It is a custom in the Coptic Church to chant it during Lent and during the month of Koyahk.

A Tale of Simple Fishermen?!

‘List of sacred net-fishermen of Athena Thoeris’ (Oxyrhynchus)

– The Oxyrhynchus Papyri vol.LXIV no.4440

11 fishermen, listed under the various districts of Oxyrhynchus. Undated, but the script is 1st century.

Now, where do we find a story about ‘fishermen’…?

Cyril

Mind of a Fanatic - St Cyril

Mind of a Fanatic - St Cyril

Not Much Left

Religious fanatics destroy a rival god