“The Samaritans were not exempt from the imposition of Hellenism … By the second century, a temple to Zeus Hypsistos stood on the peak of Mount Gerizim near the site of the Samaritan Temple.”

– K. Butcher, Roman Syria, p375.

If Josephus is to be believed, it was the refusal by a Jerusalem priest of Yahweh to renounce his “impure” wife that brought about a rival temple in Samaria. His appreciative father-in-law (who happened to be the king of Samaria) assuaged the priest’s lost status by building a copycat Temple of the Lord on Mount Gerizim. Evidently, during the era of Persian rule in Judea, the sinful taking of a foreign wife by Jewish males was a common enough practice:

“But there was now a great disturbance among the people of Jerusalem, because many of those priests and Levites were entangled in such matches; for they all revolted to Manasseh, and Sanballat afforded them money, and divided among them land for tillage, and habitations also, and all this in order every way to gratify his son-in-law.“

– Josephus, Antiquities, 11.8.2.

According to the Samaritans themselves it always was Mount Gerizim where the Lord’s temple should be built. In any event, hostility between the rival priesthoods made it easier for the Samaritans to accept a re-badging of sanctity on their holy mountain during the time of Hellenization by Antiochus IV. Zeus Hypsistos (“most high god”) now took up residence on Mount Gerizim. His shrine was subsequently destroyed by the Maccabean king John Hyrcanus in the 2nd century BC.

More than three centuries later Hadrian rebuilt the temple to Zeus and it is this temple, on the northern summit of the Samaritan holy mountain, that is attested by coinage, archaeology and written sources

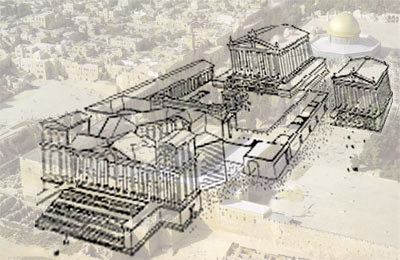

Excavations at Gerizim in the 1960s revealed a “technically sophisticated … well-built structure of monumental proportions.” (Prof. R. Bell). A grand stairway (identifiable on the coinage and noted by the Bordeaux Pilgrim) led up the side of the mountain to the sanctuary. Archaeologists identified two sacred precincts on Mt Gerizim, an earlier Structure “B” (60m by 40m) from the Persian / Samaritan period (5th – 6th century BC) and a later and slightly larger Structure “A” (65m by 44m) – from the Greek/Roman periods (2nd century BC – 2nd century AD) (Yitzhak Magen, 1982).

Here again is a guide to the structure built by Hadrian on Temple Mount in Jerusalem. At Jerusalem, as at Mount Gerizim, Hadrian’s engineers regularized and enlarged a pre-existing concourse and built a temple to Rome’s foremost god.

Hadrian’s successor Antoninus Pius (138-161) was noted for his temperate and prudent government. Yet even Antoninus had trouble with the Jews:

“Through other legates or governors, he forced the Moors to sue for peace, and crushed the Germans and the Dacians and many other tribes, and also the Jews, who were in revolt.“

– Julius Capitolinus, The Life of Antoninus Pius.

Though less lavish in his public works than Hadrian, Antoninus completed projects already begun – which included the building program at Aelia Capitolina during which his own likeness joined Hadrian’s on “Temple Mount.” Extant coinage from the period gives a good indication of the equestrian statues which stood in the plaza of the Temple of Jupiter during the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

The Bordeaux Pilgrim records that they were still to be seen in the early 4th century, though evidently he thought both statues were of Hadrian:

“There are two statues of Hadrian, and not far from the statues there is a perforated stone, to which the Jews come every year and anoint it, bewail themselves with groans, rend their garments, and so depart.”

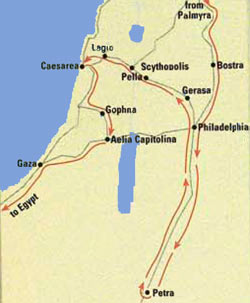

– The Bordeaux Pilgrim, Itinerary,7a.

Late into the 4th century the imperial statues were still standing, even if the Jupiter temple itself had fallen into ruin. Records the churchman Jerome:

“So when you see standing in the holy place the abomination that causes desolation: or to the statue of the mounted Hadrian, which stands to this very day on the site of the Holy of Holies.”

– Jerome, Commentaries on Isaiah 2.8: Matthew 24.15.

The visiting Pilgrim of Bordeaux (circa 333) and the resident Jerome (347-420), who spent his later life in Palestine, both testify to the equestrian statue of Hadrian. Doubtless, in their day the Jupiter temple itself was in ruin. But we can be sure that the imperial statue would not have stood in anything less than a suitably monumental plaza, and that plaza had faced an imposing Temple of Jupiter.

“They slay the ram, seemingly in derision of Hammon, and they sacrifice the ox, because the Egyptians worship it as Apis … The Jewish religion is tasteless and mean.”

– Tacitus, The Histories, 5.

It is probable that Hadrian’s new sacred precinct was comparable to similar enclosures of the time and region, such as the temples of Jupiter built at Damascus and Heliopolis (Baalbek). Each of these temples had an ornate, ceremonial entrance hall (propylaea), an hexagonal forecourt, and a central square before the main temple where equestrian and other statues stood. As it happens, a 7th century Byzantine source (Chronicon Paschale 92) lists “the square” as one of the structures built by Hadrian in Jerusalem. In Aelia the propylaea would perhaps have replaced Herod’s royal stoa on the southern end of Temple Mount.

Sagiv argues that the octagon of the Dome of the Rock was anticipated by the Roman hexagonal forecourt, and suggests the Jupiter temple faced north not south. Either orientation is possible: unlike many holy places, Roman temples were designed to be seen from the facing plaza, with no attempt at an orientation towards the sun.

Superficially, the octagonal outer enclosure of the Dome of the Rock (unique in Islamic architecture) does resemble the hexagonal Jupiter “forecourt.” But it more closely resembles the octagonal Church of the Ascension on the Mount of Olives (the original structure was built in the 4th century) or even the octagonal mausoleum of Diocletian, one of the last of the pagan emperors and nemesis of the Christians.

Hadrian’s erasure of the ruins of the Herodian temple was so complete and the expulsion of the Jews so effective that by the 4th century even the location of the temple edifice was beyond recall.

“Rabbi Yermiah, son of Babylonia came to the Land of Israel and could not find the site of the Temple.”

– Tractate Shevuot (Oaths) 1 4b.

Though its fate is unrecorded in any extant source, it is likely the Temple of Jupiter at Aelia was itself robbed out during the reign of Constantine, not long after the demolition of the Temple of Venus on the other side of the city. Hated both by Jews and Christians, the pagan “abominations” were eventually torn down late in the 4th century, probably during the reign of Theodosius.

Stone from the ruined sanctuary was looted for use in later Christian structures. On the neglected esplanade the Byzantine emperor Justinian built a church to Mary Mother of God but little else. But when he was desperate for suitable stone to build a grandly conceived basilica in the “lower city” – the “Nea” or new church – Justinian almost certainly used the destroyed sanctuary of Jupiter as his quarry.

Procopius, court propagandist for Justinian, described it thus:

” But when the impossibility of this task was causing the Emperor to become impatient, God revealed a natural supply of stone perfectly suited to this purpose in the near by hills, one which had either lain there in concealment previously, or was created at that moment …

And the Emperor Justinian endowed this Church of the Mother of God with the income from a large sum of money. Such were the activities of the Emperor Justinian in Jerusalem.”

– Procopius, Buildings Book 5