The Piety and Vengeance of Hadrian

The third decade of the 2nd century – the 120s AD – was arguably the high summer of the ancient world, the pinnacle of that age Edward Gibbon described as the ‘happiest in mankind’s history’, when ‘the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilized portion of mankind’ was ‘gently but firmly guided’ by a succession of virtuous and able emperors. The Romans were not unaware of their exceptional good fortune. Coins struck in the year 123 – the 150th anniversary of founding of the Empire – were inscribed ‘saeculum aureum’ (‘Age of Gold’). But in the fertile soil of the Pax Romana, almost unnoticed by the citizens of that remarkable civilisation, a morbid west asian cult was fabricating a creed that would, in time, subvert the values and sap the strength of Rome and return Europe to barbarism. That cult was Christianity.

Pragmatic and worldly ruler that he was, the emperor Hadrian acknowledged his debt to the deities, whatever and wherever they might be. In more than twelve years spent visiting his dominions he pointedly visited the shrines and temples of all the gods, ordering their renovation, instituting games in their honour, equipping new priesthoods for the correct observance of ritual, and so on. For his diverse benefactions he was welcomed in the east as ‘a god come down to earth’ (R. Lambert, p43).

In Rome in 121, Hadrian established a cult for the city itself and several years later, a temple, the largest in the city, was dedicated by the emperor to ‘Romae aeternae.’ Hadrian adopted Venus as patroness of the imperial family. Back in his beloved Greece again, in 123, he was initiated into the mysteries of Cabiri at Samothrace in the Aegean. The following year, in Athens, Hadrian was inaugurated into the rites of Demeter at Eleusis, and then of Dionysus. Passing through Greece, Hadrian ordered the restoration of the temple of Zeus Olympios which had lain in ruin for three centuries and the restoration of Phidias’s Zeus at Olympia and the sanctuary of Poseidon.

Towards the close of the decade, Hadrian’s entourage progressed through the provinces of southern Asia Minor: Caria, Cilicia, Cappadocia. Here, the enriched Greek cities honoured the emperor as ‘saviour and god’ (and associated him personally with Zeus). In 129 he reached Syria and the city of Antioch, where he held court for a year. In this epitome of a Hellenized city the Emperor was disturbed to recognise that, beneath the veneer, its racially mixed populace seethed with fanatical religions hostile to Rome. He downgraded the status of the city and left for Egypt.

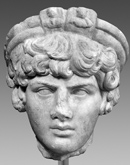

What perhaps should have been a relaxed sojourn on the Nile turned into a personal tragedy for Hadrian and an event of unimaginable consequence for the world. His male lover, a beautiful Greek youth called Antinous, his companion of several years, drowned in odd circumstances in the Nile. Inconsolable, he had a vast, new ‘sanctuary city,’ Antinoopolis, built where the incident had occurred. Modelled on Athens, the ruins of Antinoopolis were still visible in the 19th century. The city had a Christian bishop in the second century and two rival ones in the third!

Convinced that Antinous had ‘died but was reborn a god’ Hadrian instituted a new religion for his worship, complete with temples and annual games. The core belief was that this virtuous young man, by self-sacrifice, had conquered death and now offered similar salvation and protection to others.

An epitaph for Antinous recounts that he had ‘appeared after death in dreams to provide cures for the sick.’ He was an authentic Greek ‘Hero,’ a human who had attained immortality and could intercede with the gods. With official sponsorship and encouragement, his shrines, images and priesthoods appeared throughout the empire – except in Antioch. His was the only non-imperial head to appear on coins, and his statue is the most common from antiquity, save for Augustus and Hadrian himself. In the 4th century, re-worked statues of Antinous showed him holding the grapes of Dionysus in one-hand – and a cross in the other!

In foul temper, Hadrian moved his court on to Judaea, where he was in no mood for Jewish intransigence. The Emperor decided upon a thorough-going Hellenization of the province.

For sixty years Jerusalem had lain waste. On its ruins, as his gift to the Jewish people, Hadrian ordered the construction of a new city, complete with forums, theatres, baths, gymnasia and all the other amenities of a modern polis. This he named Aelia Capitolina – to honour his family (Aelius) and Zeus himself (whose temple in Rome graced the Capitol hill). On the spot which had once been an ancient quarry arose a vast new temple to Aphrodite and close by, where the Jewish temple lay in ruins, a temple to Jupiter-Zeus. In its atrium, Hadrian had placed a giant statue of himself, benefactor and ruler of the world.

Pagan Tolerance and Restraint

“I received a letter from your illustrious predecessor Serenus Gratianus, and I do not wish to leave his inquiry unanswered, so that innocent men are not troubled and false accusers seize occasion for robbery.

If the provincials are clearly willing to appear in person to substantiate suits against Christians, if, that is, they come themselves before your judgment seat to prefer their accusations, I do not forbid them to prosecute.

But I do not permit them to make mere entreaties, and protestations. Justice demands that if any one wishes to bring an accusation, you should make due legal enquiry into the charge.

If such an accusation is brought and it be proved that the accused men have done anything illegal, you will punish them as their misdeeds deserve

But, in Heaven’s name, take the very greatest care that if a man prosecute any one of these men by way of false accusation you visit the accuser, as his wickedness deserves, with severer penalties.”

– Hadrian, Rescript To Minicius Fundanus, Governor of Asia (124 AD).

To the Jews, Aelia and its statue of Hadrian were the ‘abomination of desolation.’ For them, the final provocation was Hadrian’s ban on circumcision (which applied to Egyptians and Arabs as well as Jews). As the most Hellenized of all Roman emperors, Hadrian regarded circumcision as nothing less than mutilation.

The Emperor returned to Rome. Hardly had he done so than news reached him that the Jews, armed with weapons secreted for years, had staged a revolt.

“At this time, the Jews started a war because they were forbidden to mutilate their genitals.”

– Historia Augusta, Hadrian, 14.2.

A new ‘messiah’ had been identified – an adventurer claiming Davidic descent called Simon ben Kosiba (punned into a portentous ‘Bar Kochba’ or ‘son of the star’ by his followers). He was led on a horse – ‘as prophecy foretold’ – through Jerusalem by the aged Akiba.

Kosiba/Kochba’s messiahship was endorsed by the High Priest Eleazar and even the normally pro-Roman Sanhedrin. Aelia was torched and a re-dedication made on the temple ruins. War with Rome was now inevitable.

Catching the Roman forces off-guard and out-numbered, the rebels seized control of Jerusalem. The Roman governor, Tineus Rufus, ordered his garrison to evacuate the city as best they could and they retreated towards Caesarea. His command, the X Legion Fretensis, had as its emblem a wild boar – a provocative ‘pig’ to the Jews. Rome’s initial response was to assign the XXII legion, based in Egypt, the task of retaking the city but such was the fury and force of the rebels that the legion was destroyed before it got anywhere near.

When the full extent of the uprising was gauged in Rome, the Emperor dispatched Julius Severus, victor of the recent war in northern Britain, at the head of two legions, to suppress the rebellion. The war proved protracted and merciless. The rebel forces, perhaps half a million strong, adopted a guerilla-style warfare which denied the Romans a decisive battle, favourable to their cavalry and the use of the phalanx.

“The Jews … did not dare try conclusions with the Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved underground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light.

Soon, however, all Judaea had been stirred up, and the Jews everywhere were showing signs of disturbance, were gathering together, and giving evidence of great hostility to the Romans, partly by secret and partly by overt acts; many outside nations, too, were joining them through eagerness for gain, and the whole earth, one might almost say, was being stirred up over the matter.”

– Dio Cassius, Roman History, 69.9.12-13.

Drawing troops from everywhere from Egypt to Syria a full-scale invasion force was assembled. Twelve legions were ultimately to be deployed in the province, systematically annihilating hundreds of towns and villages. Jerusalem was retaken only in the third year of the war. Akiba and nine other ‘doctors of the Law’ were executed although some fanatics escaped to Persia. After three years of attrition, Simon and the last of the rebels, plus many refugees, were trapped in the fortress of Bethar, south west of Jerusalem. Hadrian himself joined the besiegers for the final capitulation. Famously, he refused to accept a Triumph for this brutal war.

The Romans had been badly mauled – ninety thousand troops lost in conflict and related pestilence. Yet the cost to the Jews was total: the end of their existence as a self-governing nation within the Empire; half a million war-dead (from a nation of perhaps three million); tens of thousands sold into slavery and the arena. Even the name of Judaea was erased from the map, replaced by ‘Siria Palestinia.’

On pain of death, Jews were forbidden to enter the new city of Alia – rebuilt more modestly – save for one day a year, to mourn their lost temple. On the holy mountain of the Samaritans Hadrian erected a temple to Zeus, embellished with the bronze doors taken from Jerusalem. For a time, study of Jewish scripture was outlawed, as was also the keeping of the Sabbath. The ‘pious’ resistance of the Jews had exacted a terrible human price.

Throughout the year 135, the Mediterranean ports were flooded with Jewish refugees and the slave markets overflowed with captives. With the catastrophic defeat a new pun on Bar Kosiba’s name was coined by the rabbis: ‘bar Kozeba’, meaning ‘son of the lie’. Only the Christian Jews, who harboured a resentment against the rest of the tribe, drew comfort from the disaster. The Romans, they reasoned, were the instrument of divine wrath, incurred by the Jews for the rejection of their prophet.

“And thus, when the city had been emptied of the Jewish nation and had suffered the total destruction of its ancient inhabitants, it was colonized by a different race … And as the church there was now composed of Gentiles, the first one to assume the government of it after the bishops of the circumcision was Marcus.”

– Eusebius Pamphilus, Church History, 4.6.

Marcus? Marcus? Now there’s a name to ponder …

Conventional estimates suggest a population for the Roman empire of 50-60 million at the time of Hadrian, with Jews numbered perhaps 4-5 million. In comparison, Christians of various stripes numbered 10,000 at most, a tiny minority, unnoticed by Rome. Even in the 3rd century the historian Herodian does not mention them.

But the estimated number of Jews, so-called, may be woefully misleading.

Most Jews within the Roman Empire were NOT exiles from Judaea, nor were they descendants of exiles. Although, in consequence of the Jewish wars, trouble-makers were enslaved in considerable numbers and elite elements fled or were exiled from their homeland, the majority of Jews (Judaeans) – peasant farmers in the main – remained in Siria Palestinia. Rome had neither the means nor the desire to exile an entire population (and hence such a migration appears nowhere in Roman or Jewish histories). In later centuries they were to be increasingly oppressed by Byzantine Christians and in consequence welcomed the armies of Islam in the 7th century. Gradually, these Jews converted to the new faith and became Palestinians (something acknowledge by the first Zionists).

The majority of Jews outside of Palestine were the descendants of converts from the indigenous pagan populations, won over by energetic proselytizers in Judaism’s most expansive era. Judaism became a successful evangelizing religion in the 2nd and 3rd centuries (as Roman historians attest), and took variegated forms. Its success prepared a seedbed for factions which jettisoned Judaism’s least appealling characteristics and were no longer shaded by the Jewish penumbra – in a word, Christians.

With Christianity’s own triumph in the 4th century the momentum within the Roman empire for conversion to Judaism ceased. Indeed, “adoption of Jewish manners” became an illegal activity, and faced with official hostility the descendents of converts to Judaism found it prudent to convert to the favoured Christianity. But Jewish proselytizing continued in regions beyond the reach of Rome. Thus Iranians of Adiabene, Ethiopic tribes of the Horn of Africa, Arab tribes of the Yemen and Spasinou/Charax, Berber tribes of north Africa, and Turkic tribes of the Caucasus (Khazars), all in time embraced the religion of Judaism. Berber Jews in the army of the Caliph would seed the Jewish community in Spain and Khazar Jews would seed the Ashkenazi Jewish communities of eastern Europe

“The Jews as a self-isolating nation of exiles, who wandered across seas and continents, reached the ends of the earth and finally, with the advent of Zionism, made a U-turn and returned en masse to their orphaned homeland, is nothing but national mythology.”

– Professor Shlomo Sand, Tel Aviv University, The Invention of the Jewish People.

The central idea of Zionism, that Jews should “return from exile” to a reclaimed homeland is starkly at odds with the demographic reality that very few Jews can make any legitimate claim to ancestral origins in the Levant. Even more alarming is that Christian Zionists energetically support the “return” of the Jews as a catalyst for the return of their own equally imaginary originator.

“Antinous was from Bithynium, a city of Bithynia, which we also call Claudiopolis; he had been a favourite of the emperor and had died in Egypt, either by falling into the Nile, as Hadrian writes, or, as the truth is, by being offered in sacrifice. For Hadrian, as I have stated, was always very curious and employed divinations and incantations of all kinds. Accordingly, he honoured Antinous, either because of his love for him or because the youth had voluntarily undertaken to die, it being necessary that a life should be surrendered freely for the accomplishment of the ends Hadrian had in view, by building a city on the spot where he had suffered this fate and naming it after him; and he also set up statues, or rather sacred images, of him, practically all over the world. Finally, he declared that he had seen a star which he took to be that of Antinous, and gladly lent an ear to the fictitious tales woven by his associates to the effect that the star had really come into being from the spirit of Antinous and had then appeared for the first time.

– Dio Cassius, Roman History, 69.9.11.

Antinous:

Hadrian’s male lover, a beautiful Greek youth from Bithynia (modern Turkey) and companion of several years. He drowned in odd circumstances in the Nile and speculation suggested a ritual suicide to somehow prolong the Emperor’s own life.

A distraught Hadrian convinced himself that the dead Antinous had been ‘reborn a god’ and instituted a new religion for his worship, complete with temples, priests and annual games.

Apparently, the self-sacrificing Antinous had conquered death and now offered similar salvation and protection to others. What an interesting idea!

An epitaph for Antinous in Rome recounts that he had ‘appeared after death in dreams to provide cures for the sick.’

The cult continued for three hundred years but slowly got subsumed into a more truculent cult – Christianity. In the 4th century, re-worked statues of Antinous showed him holding the grapes of Dionysus in one-hand – and a cross in the other!

“It is remarkable that [the cult of Antinous] should have survived as long as it did, well into the 4th century”

– S. Perowne (Hadrian, p159)

Antinous

Sprouting wings – the deified Antinous (Naples)

Antinous sculpted as a priest of Attis, the lover of Cybele.

Museo Nazionale Romano

- Royston Lambert, Beloved & God (Phoenix, 1984)

- Dan Cohn-Sherbok, The Crucified Jew (Harper Collins,1992)

- Henry Hart Milman, The History of the Jews (Everyman, 1939)

- Josephus, The Jewish War (Penguin, 1959)

- Cassius Dio, Roman History (Book 69.12-14)

- Leslie Houlden (Ed.), Judaism & Christianity (Routledge, 1988)

- Karen Armstrong, A History of Jerusalem (Harper Collins, 1999)

- Michael Grant, The Roman Emperors (Weidenfield & Nicolson, 1985)

- A.M. Renwick, The Story of the Church (Inter-Varsity Press, 1958)

- Norman Cantor, The Sacred Chain – A History of the Jews (Harper Collins, 1994)

- Shlomo Sand, The Invention of the Jewish People (Verso, 2009

Dwarfs on the Bones of Giants – Emperors Hadrian and Charlemagne compared

Militant Tendencies – Jewish Resistance to Roman Rule

Trajan Conquers the East – ‘Wars & Rumours of Wars’

Rabbinic Judaism Inc. – A Portable God for the World’s First Multinational Business

Hadrian’s Villa

Grandeur even in ruin

Emperor Hadrian (117-138), one of the most remarkable and talented men Rome ever produced.

Hadrian was a successful military commander, an outstanding administrator and reformer, a superb architect, a philosopher and a poet.

“Little soul, wandering and pale, guest and companion of my body, you who will now go off to places pale, stiff, and barren, nor will you make jokes as has been your wont.”

– Hadrian, in poetic mood.

‘Greek thought, like the architecture which expressed it, concentrated on man as the measure of all things, as an ideal, not only in mind, but in body as well…

In the Jewish idea man was the humble servant of a supreme and sublime God. Of himself he was nothing…’

– S. Perowne (Hadrian, p136/7)

Provocative boar of Legion X Fretensis

Halfway to Christ

God-man Antinous holds a cross in one hand – and the grapes of Dionysus in the other!

(Stele from Antinoopolis. Berlin)

Antinous became a symbolic focus for the last of the pagans.

His images were popular until the final prohibitions of Theodosius in 391. Notice the genitals – no fig leaf yet!

Hadrian deals with rebellious Jew

Restless Jews

“More & more (the Jews) cultivated the nationalist myth, naming their children after the Hebrew patriarchs and dreamed still of a Messiah who should arise to set his people free and restore Jerusalem.”

– S. Perowne (Hadrian, p139/140)

“Both by his example and by his precepts Hadrian so trained and disciplined the whole military force throughout the entire empire that even today the methods then introduced by him are the soldiers’ law of campaigning.”

– Dio Cassius, Roman History, 69.9.

Restless Jews

Obelisk to Antinous (2nd century, Rome), commemorates ‘Osiris-Antinous the Just’.

The epitaph records that Antinous ‘appeared after death in dreams’.