The Companions of Mithras

Every sun god needs his retinue of followers!

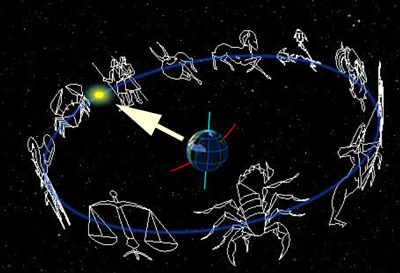

In much of the iconography of Mithras the god was associated with the zodiac, the twelve figures that the imaginative ancient mind discerned in the night sky. Like the sun itself, the stars were eternal yet unknown entities, forever looking down on the affairs of man. As the earth annually orbited the sun, the night sky presented to human observers a varying selection of stars month-by-month throughout the year. By a process of “joining up the dots” any number of two-dimensional figures might be imagined bounded by the points of starlight. In their attempt to make sense of this mystery, the first Babylonian (or “Chaldean”) and Indian observers assigned animals to most of their stick figures, twelve in number.

It was thus apparent that the imagined creatures in the night sky, together with the moon, were perpetual associates of the sun god. Further speculation interpreted the star-animals as “signs”, and associated them with the “wandering” planets, the four elements, the lower powers, metals, and even with human personality traits determined at the moment of birth. With human destiny thus governed and presaged by events in the heavens (the word disaster derives from the Latin for ‘ill star’), equinoxes and solstices were particularly ominous or auspicious events, and astrologers who claimed the ability to cast horoscopes and divine the future were both sought after and feared.

Companions of Mithras

Represented in relief on most tauroctonies, the figures that accompany Mithras are also often found as free-standing sculptures. They are an enigmatic collection of supporting characters. Although tantalisingly beyond our reach, it is clear that the Mysteries of Mithras were imbued with a profound astrological content.

Aion/ Zervan

– the lion-headed

Leontocephalous

deity of Eternal Time/ Kronos / Saturn

Mithraeum, Sidon, Syria

Crouching lion (Osterburken)

Cautes

– torch-bearer

Both torch-bearers are aspects of Mithras himself: the “up torch” bearer was the rising sun; the “down torch” bearer was the setting sun.

Together with Mithras proper – the sun at its zenith – the trio made up a divine trinity.

Cautes is sometimes shown with a cock (herald of the dawn).

Cautopates

– torch-bearer

Sol/Helios

Sol drives his four-horse quadriga up to heaven.

Luna/Selene

Luna drives her two-bull biga down to the abyss.

Phosphorus

– dawn

(aka Eospherus, Lucifer, Morning Star).

And Jesus?

![]()

“I am the root and the offspring of David, and the bright and morning star.” – Revelation 22.16.

Hydra – snake

Canis – dog

The dog and the serpent (crested snake) lap the life-giving blood.

(Marino)

Scorpio –scorpion

The scorpion grasps the testicles of the bull. (Venezia)

Corvus/ Corax – raven/crow

The messenger.

Mercury

Favonius/Zephyrus – good/warm wind

Auster/ Boreas –bad/cold wind

(Osterburken)

Mithras and Sol – a convergent relationship

“The Mithraic cult … was the most syncretistic of all the cults and religions … This caused it to lose its strength, definiteness, and cohesion.”

– Antonia Tripolitis, Religions of the Hellenistic Roman Age, p59.

The official Roman cult of Sol Invictus (the Invincible Sun), at first consideration, appears to stand apart from the Mysteries of Mithras. The cult of Sol Invictus was, after all, a public spectacle, a celebration open and visible to all. The Mithraic mysteries, in contrast, were a male-only fraternity, functioning in secret in small chapels.

And yet, in fact, the two aspects of Roman sun worship almost certainly complemented each other. The failure of Rome to openly endorse Mithras in the early empire may have owed something to its Persian connection but the cult of Sol Invictus as practiced in the later Empire owed much to Mithras. As iconography bares out, Mithras was indeed conflated with the Invincible Sun, Mithras Sol Invictus.

Initially, Mithras was a distinct and even rival entity to the sun god Sol but over time the two deities became allies and associates and eventually merged into an all-embracing invincible sun-god cult. The process began in the Hellenistic world, with the conflation of Mithra with Helios, Apollo, and perhaps even Perseus. Within the Roman world, as the god moved from marginal and esoteric cult to mainstream deity, so the distinct identity of Mithras merged into the persona of the invincible son, Sol Invictus.

Sol, the figure on the left in the upper panel, genuflects before Mithras.

Mithraeum at Marino, Italy (2nd century)

(Right) In the upper half of the panel, a similar scene of obeisance, with Sol gesturing in deference before Mithras.

In the bottom panel, Sol makes an offering on an altar. The two gods are reconciled.

(Upper left) Mithras rides off triumphant, accompanied by his dog (Canis?) and a servant (Cautes?).

(Lower left) In the final scene, the two gods share the sacred meal, reclining on a couch.

From the Tauroctony of a Roman fort at Osterburken, near Heidelberg. (Karlsruhe Museum).

Rival sun gods become allies and merge

Mithraeum, Dura Europos, Syria (c 210. Yale)

Mithras merges with his friend ‘Sol’.

An illustration of the syncretic migration of features from Mithras to the Sun god.

(Left) Both figures wear identical cloaks and embroidered, long-sleeved Persian tunics.

But whereas the wide-eyed Mithras is curly haired and sports a Phrygian cap, Sol is bare-headed and is highlighted by a nimbus.

The blending of Mithras with Sol Invictus can be seen in these examples (right), where the Phrygian cap of Mithras is actually perforated by the radiant crown of Sol.

(Left) The final fusion –

Mithras Sol Invicto Deo

Notice that here, on an image meant for public display, much of the symbolism of the mysteries has been omitted.

(Vatican Museum)

Petronell-Carnuntum, Austria.

Altar, Carrawburgh Mithraeum (Newcastle, UK)

And Jesus?

The nimbus (arc of the sun) was of course copied by the Christians for their own sun god.

Mithras, Cybele and Attis – a close relationship

It has sometimes been argued that the initiates of Mithras entered an “ordeal pit” where they were baptised in the blood of a ritually slaughtered bull (“a satanic parody of Christian baptism”). But in fact the modest chapels of the Mysteries of Mithras were far too small for such rites. Baptisms in bull’s blood did occur but rather as a rite of the cult of Cybele and Attis, gods of Phrygian origin.

In a lurid account from a hostile Christian source (Prudentius, Peristephanon) would-be priests of Cybele, the Great Mother goddess (Magna Mater to the Romans), were required to descend into a pit, which was then covered by boards filled with holes, and the blood of a sacrificial bull above would shower onto them. Blood from the sacrificed animals was believed to confer strength and long-life to those on whom it fell. Thus sanctified, the newly baptised would emerge from the pit “reborn to eternity” (or perhaps to Attis). The Phrygian cult passed to Rome a century before Mithraism, at a low-point in Rome’s struggle with Carthage. Priests of Cybele emulated the fate of Attis, son and consort of the goddess, by self-castration, a ritual shocking even to the Romans.

During the imperial period the cult of Magna Mater underwent various changes. Claudius raised Cybele into the Roman state pantheon (where she would eventually merge with other goddesses, such as Artemis, Isis and Demeter), and he allowed Roman citizens for the first time to join the cult’s effeminate priesthood – the galli. License to castrate themselves, however, was subsequently withdrawn by Domitian, although the priests remained self-flagellant cross-dressers.

During the reign of Antoninus Pius, the Magna Mater bull sacrifice became a central drama of an important Roman state festival, the Megalensia, and a high priest (archigallus) was appointed to officiate during the sacramental procession and celebratory games. The ritual of the taurobolium continued into the reign of Diocletian. Even after the triumph of Constantine, the bull sacrifice was celebrated in Rome by defiant pagan aristocrats – strikingly, on the site where the Vatican now stands!

Echo of an ancient syncretism?

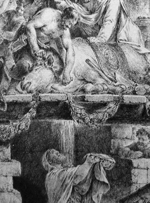

From Ostia

High priest (archigallus) gives offerings (testes?) before Cybele and Attis.

Same high priest with the torches and torchbearer of Mithras.

The Brotherhood – Seven grades, planets, metals, days

“Mithraism was an archetypal mystery cult and secret society. Like the rites of Demeter, Orpheus, and Dionysus, the Mithraic rituals admitted candidates by secret ceremonies, the meaning of which was known only to the initiated.

Like all other institutionalized initiation rites of the past and present, this mystery cult allowed the initiates to be controlled and put under the command of their leaders. Preceding initiation into the Mithraic fold, the neophyte had to prove his courage and devotion by swimming across a rough river, descending a sharp cliff, or jumping through flames with his hands bound and eyes blindfolded.

The initiate was also taught the secret Mithraic password, which he was to use to identify himself to other members, and which he was to repeat to himself frequently as a personal mantra.“

– David Fingrut, Mithraism, The Legacy of the Roman Empire’s Final Pagan State Religion.

A fortuitous survival from ancient Ostia is the mosaic floor of the Mithraeum of Felicissimus, which depicts the seven grades of the Mithraic brotherhood, together with their ritual objects.

This structure of seven grades may correspond in some way to the development of the mysteries, particularly as the cult made its way from Asia and across the Roman world. The pagan Celsus reports that in the Mithraic mysteries “the soul moved through seven heavenly spheres, beginning with the leaden Saturn and ending with the golden Sun.” It has been argued (Clauss, 1990) that many members of the Mithraic mysteries may not have been graded at all, in which case those holding ranks would be something of an elite. On the other hand, judging from the dedications made to Mithras, it appears that no social barriers prevented slaves or common soldiers holding positions in the Mithraic hierarchy.

The seven grades of Mithraists, wearing distinctive costumes (Bronze plaque, Budapest)

Astral symbolism – but was it precession of the equinoxes?

In the 1970s David Ulansey offered a new explanation for the Mysteries of Mithras, rejecting any dependence on earlier Persian Mithra worship. Ulansey’s point was that Mithraism as known to the Romans was essentially a home-grown product, markedly different from anything found in the east. The key, argued Ulansey, was the “precession of the equinoxes”, an hitherto unknown movement of the entire heavens discovered by Hipparchus, the Greek astronomer, sometime around 130 BC. Hipparchus had noted the “displacement” of the solstices/equinoxes over vast periods of time and concluded they were “precessing” through the zodiac. Thus, 2000 years earlier, the spring equinox, slowly but inexorably, had moved from the constellation of Taurus the Bull into Aries the Ram (with a corresponding movement of the autumn equinox from Scorpio into Libra).

Ulansey speculated that this discovery prompted Stoic philosophers in Tarsus to reason that a new god (Perseus yet called by the old name Mithras?!) was responsible for these awesome realignments in the heavens. In a cosmic and mystical sense, the sun-god had “slain the bull”. The result was the defining iconography of Mithraism – the Tauroctony. All now could be explained in terms of astrological symbolism, the scorpion grasping the bull’s genitals represented the constellation Scorpio; the dog and snake seeking the bull’s blood being the constellations Canis Minor and Hydra.

Although popular for a time, there are flaws in this theory. On the one hand, there were undeniable statements from the Romans themselves that Mithraism was the “Persian religion” (and even one of the cults higher grades was Perses (Persian). One of Rome’s strengths was its ability to assimilate whatever it found useful, and a martial cult, stressing stoicism and loyalty, was certainly useful in an age troubled by endemic civil war. On the other hand, the “precession” does not stop, and even in the period of late republican Rome, the spring equinox was already moving away from Aries and into Pisces. Moreover, “astrological symbolism” leaves much unexplained. Today, Mithraic scholars take a more nuanced view. Yes, Rome’s Mysteries of Mithras was considerably more developed than anything that can be traced in the east; but that eastern origin and character is not to be denied.

Winners and Losers

The cult of Mithras was of very ancient lineage, traceable in one form or another through at least two thousand years. In origin it was primordial sun-worship – the father of all religion. But it was also an eastern religion, reaching the Roman world from India via Persia. As it was carried west, it took on distinctive and original forms, suited to Roman tastes. Mithraism anticipated Christianity in all major respects, and enjoyed a popularity for at least four centuries. It peaked around the year 300 when it became the official religion of the empire. At that time, in every town and city, in every military garrison and outpost from Syria to the Scottish frontier, was to be found a mithraeum and officiating priests of the cult. But it faced a determined, organised and intolerant opponent and Mithraism lost the battle. Yet much of its ritual and regalia was, without embarrassment, absorbed by the conquering faith of Christ.

In the 4th century, ordinary Christians had not yet acquired the abject humility and submissive behaviour that would characterize the brethren of later centuries. In church, they sang, danced and clapped.

And when they prayed it was facing to the East, with hands held wide and with face held up, not down – to greet their sun-god!!

Sources:

Malachi Martin, The Decline & Fall of the Roman Church (Secker & Warburg, 1981)

Kevin Butcher, Roman Syria & the Near East (British Museum, 2003)

Michael Parenti, History as Mystery (City Lights, 1999)

John G. Jackson, Christianity Before Christ (American Atheist Press, 1985)

S. Angus, The Mystery Religions (Kessinger Publishing, 2003)

Antonia Tripolitis, Religions of the Hellenistic Roman Age (Eerdmans,2002)

David Ulansey, The Origins of the Mithraic Mysteries: Cosmology and Salvation in the Ancient World (OUP, 1991)(link)

Everett Ferguson, Backgrounds of Early Christianity (Eerdmans, 2003)

Franz Cumont, The Mysteries of Mithra (1896, 1899)

Engelbert Winter, “Mithraism & Christianity in Late Antiquity”, Ethnicity & Culture in Late Antiquity (Duckworth, 2000)

Manfred Clauss, The Roman Cult of Mithras: The God and His Mysteries

Roger Beck, The Religion of the Mithras Cult in the Roman Empire: Mysteries of the Unconquered Sun (OUP, 2007)

Roger Beck, “The Mysteries of Mithras: A New Account of their Genesis”, The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. LXXXVIII, (1998)

Roger Beck. Beck on Mithraism (Ashgate, 2004).

G. R. S. Mead, The Mysteries of Mithra (Theosophical Publishing Society, 1907)

M. J. Vermaseren, Corpus inscriptionum et monumentorum religionis mithriacae (2 vols., Martinus Nijhoff, 1956, 1960)

Porphyry, De astro nymphorum (On the cave of the nymphs)

Mithraeum. Our Common Sun

The sun never actually appears against the night sky. The priest-astronomers of the ancient world made a reasonable conjecture that the sun was following a course – the “ecliptic” – through an eternally fixed arrangement of “animals”, the observable stars.

But the earth’s tilt on its axis (“inclination of the ecliptic”) caused another misapprehension: that the sun was swinging up and down according to the seasons: in the northern hemisphere, appearing at its highest on the summer solstice and lowest on the winter solstice.

This rhythmic course was drawn as a band, 8° either side of the median, on a great, enclosing celestial sphere.

The Greeks named this band the zodiac, from the word for animal.

Tauroctony (Neuenheim, Germany).

Mithras killing his bull, encircled by the signs of the zodiac.

(c.150 AD – Mithraeum, London)

Sol Invictus (Rome)

Invincible Sol

Altar of The ‘Invincible Sun’ (Invicto Soli).

Invincible Mithras

Funerary Stela: The Invincible Mithra (Invicto Mythra Dio) (Romania)

Invincible Sun God Mithras!

D S I M (Deo Soli invicto Mithrae) (Vienna)

Altar dedicated to the “Unconquered Sun God Mithras, Protector of the Empire” at Carnutum in Pannonia in 308 by Diocletian and his co-emperors.

Unlike in the Mysteries of Mithras, priestesses were allowed to serve the cult of Cybele/ Attis.

“Today the Vatican stands where the last sacrament of the Phrygian taurobolium was celebrated.“

– S. Angus, The Mystery Religions, p235.

Lucky 7

“There were seven degrees of initiation into the Mithraic mysteries … The fathers conducted the worship. The chief of the fathers, a sort of pope, who always lived at Rome, was called ‘Pater Patrum’ or ‘Pater Patratus.‘ “

The Christian church would establish seven holy sacraments, as well as codify seven deadly sins.

“The Seven Deadly Sins, which Christians appropriated both iconographically and geographically in their own views of Hell, were a Mithraic formulation which looked back to Zoroastrianism, which gave mystic significance to the number seven.

Mithra also gave us … the Chi-Rho sign which Christians appropriated.”

– Alice Turner (The History of Hell, p36)

Initiation by Trial

Naked and blind-folded.

The Pater performs the function of Mystagogue (initiating master) on a neophyte. The mithraic father is likely to have maintained the community and temple at his own expense.

Tertullian (“The Soldier’s Crown“) describes the initiation to the rank of Soldier. The initiate is offered a crown at the point of a sword but waves it aside, proclaiming “his only crown is Mithras.”

In another ceremony (“a parody of the resurrection“) the initiate is confronted with a bloody sword and an apparently dead man (who, evidently, “returns to life”).