Barabbas, Barabbas!

Evil twin?

If Barabbas was the revolutionary, then who was it that really caused mayhem in the temple, Jesus or Barabbas? And why does a peace-loving Jesus tell his followers to sell their cloaks and buy swords (Luke 22.36)?

Then again, perhaps it’s all theatre!

Mark’s dark cameo

ἦν δὲ ὁ λεγόμενος Βαραββᾶς μετὰ τῶν στασιαστῶν δεδεμένος, οἵτινες ἐν τῇ στάσει φόνον πεποιήκεισαν.

“And among the rebels in prison, who had committed murder in the insurrection, there was a man called Barabbas.”

– Mark 15.7.

As he moved his religious drama towards its climax, Mark introduced a new character into his story. This was a figure not anticipated by anything that has gone before and who had a role which was quite superfluous to the melodrama’s preordained outcome. The audience has been told repeatedly, that Jesus the Nazarene was the “son of man”, chosen by God as his own son to be betrayed and killed. Yet the death of Jesus (three-day wonder that it was) was the required “ransom for many” (Mark 10.45) demanded by a just God. With the shedding of holy blood, and the debt of sin repaid, all who “believe the gospel” will be saved. In short, the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus required no link to the fate of another person; there could be no last-minute reprieve, the salvation of humanity was at stake.

But into the final passion scenes of his gospel, Mark intruded a striking cameo: a guilty man, a murderer no less, who was set free!

Hitherto, Mark had never spoken of “rebels in prison.” This is the first and only time, we hear of “the insurrection” (τῇ στάσει). But this is the context – the Jewish War – from which Mark draws a foil to set against his peace-loving hero. Mark’s inclusion at this point of a “revolutionary”, in prison with other rebels, was deliberately chosen.

The Jewish high council has already condemned Jesus as deserving death (Mark 14.64). Those same chief priests now agitate the crowd to clamour for the release of a revolutionary (Mark 15.11). The iniquity of the Jewish leadership is underscored by this ludicrous event.

But Mark is not merely setting out a tale of salvation, he is putting his story in context and presents his intended audience with a real choice: between rebellion against Rome or a “Kingdom of God”, soon to materialise on earth.

The foolish and hard-hearted Jews, led astray by their leaders, had recently and disastrously made the wrong choice, they had chosen rebellion. Many had died or been enslaved. The temple had been destroyed and its priests scattered. Jerusalem and many other towns lay in ruin. Even so, many Jews still hoped for the military overthrow of the Romans. Mark personified these alternatives facing the Jews as a choice between a political revolutionary – a false messiah – and the chosen one of God, Jesus Christ, the true messiah. Those who chose Jesus Christ, wrote Mark, would have life.

That was Mark’s “political” message within his religious drama.

Uncustomary custom

To intrude a revolutionary into his story Mark had to invent a “custom”, a startling disposition on the part of the Roman governor to release at the Passover one prisoner named by the Jews.

“Now at the feast he used to release for them one prisoner for whom they asked.” – Mark 15.6

Now, certainly, it was well within the remit of a Roman governor to release a prisoner held in his custody. We have an example of just such a release from this very place and time. Arrested and flogged by the Romans, Jesus ben Ananias was released by the governor of Judea as nothing more dangerous than a mad man (Josephus, Wars 6.3).

The novelties in Mark’s story are that the amnesty had become an annual event, coinciding with the Passover festival, and that though the Roman jail might have been crammed with prisoners, only two individuals are ever considered for release. Somehow “the Jews” – in fact, a random crowd who gather in the governor’s courtyard – have collectively gained the right to name a prisoner to be released.

The dubious possibility of such a custom – quite unknown in the histories of Rome or the Jews – becomes certain fantasy when, evidently, there were no restrictions placed upon which prisoner might be released, not even exempting a murderous enemy of Rome! No Roman governor would ever have released such a criminal, and certainly not because of his own “custom” and not because a crowd had gathered and chanted a name.

Romans behaving oddly

Mark’s theatrical device of the “Passover pardon” owed nothing to reality. In the real world, Pilate could have released Jesus forthwith, all the more likely if he thought him innocent. The governor needed no special amnesty to do so. Even if – “wishing to satisfy the crowd” (Mark 15.15) – Pilate had responded to the baying mob by releasing their own choice he could still have released Jesus. Or kept him in his cells for further consideration.

Yet according to Mark the governor behaved very oddly. He engaged with the crowd, allowing the mob to decide what he was to do with a second prisoner, Jesus.

Pilate again said to them, “Then what shall I do with the man whom you call the King of the Jews?”

And they cried out again, “Crucify him.” – Mark 15.12,13

Pilate lets the crowd gathered outside his praetorium decide the fate of a prisoner that he himself suspected was innocent. This is more than a “customary release of one prisoner” – it was mob rule.

None of Mark’s fantastic drama bears the slightest historical scrutiny. Pontius Pilate was not a weak and indecisive man, a patsy of the chief priests, easily intimidated by a Jewish crowd. He was a tough guy who had at his back a whole battalion of troops. Both Josephus and Philo recorded something of the real character of Pilate:

Philo described Pilate as a man of “inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition” whose administration was characterised by “greed, violence, robbery, assault, abusive behaviour, frequent executions without trial, and endless savage ferocity.” (Embassy to Gaius, 301-2)

Josephus confirmed Philo’s judgment, recording several episodes of Pilate’s brutality and contempt for the Jews. In Judea “a great number” were slain protesting an aqueduct. In Samaria, “a great band of horsemen and foot-men … fell upon those that were gotten together“, an incident which provoked protests to Vitellius, the Roman Legate of Syria. Vitellius, rather more sensitive to geopolitical considerations, removed the Prefect who had plundered the province of Judea for a decade.

This was not a man subject to the whims of a Jewish crowd.

Doppelgänger

Mark named his revolutionary leader “Barabbas”, a curious name which has generated an enormous amount of literature.

“Barabbas” quite clearly is a Hellenized contraction of the Aramaic “bar Abba”, son of the father. Mark himself clarified a similar construction with regard to a blind man, “a son of Timaeus, Bartimaeus” (υἱὸς Τιμαίου Βαρτιμαῖος) at 10.46. The curiosity, of course, is that according to Mark Jesus had often referred to himself as the Son of the Father (for example at Mark 14.36, he prayed to “Abba, Father …”) and now he appears to have been challenged by a figure whose own name meant precisely “son of the father”. Could both such characters really have been in Pilate’s jail at the same time? Nothing at all is known of any such Barabbas beyond this brief moment of infamy in the gospels. The name Barabbas appears nowhere else in the New Testament and has no history.

So where did Mark get the name “Barabbas” (Hebrew בר אבא, Greek Βαραββᾶς, with a final “s” added to the Greek to indicate genitive)?

Mark repeatedly created telltale names, for both places and people. The “Sea of Galilee” was never so named before Mark styled it so. Along its shore he placed the unknown cities of Dalmanoutha (a harbour) and by inference Magdala (a hometown for Mary “Magdalene“). Elsewhere he created Arimathea (good disciple town). The sons of Zebedee, he styled “Boanerges or sons of thunder“, modelling them after Castor and Polydeuces, the sons of Zeus, “the thunderer”. Iscariot was another Markan creation.

In Mark’s story, the release of Barabbas is followed by the mocking of Jesus, a scene pre-figured in a work by the Jewish writer Philo. In Flaccus, a text familiar to the Christians, Philo recorded the mocking of the Jewish king Agrippa on a visit to Alexandria. In Mark’s text Jesus, the true “king of the Jews”, was mocked in a very similar manner. The lampoon was inflicted on a “certain madman named Carabbas”. Given the multiple parallels between the Flaccus passage and his gospel, there is more than a possibility that Mark changed “Carabbas” into “Barabbas” – and in the process created a rather clever pun. He may even have originally written Bar Rabban (as per Jerome, Gospel according to the Hebrews), a name meaning “son of a teacher” (that is, of the Jewish law), chosen as another way of incriminating the Jews.

Flaccus

Carabbas

Taken to a public hall

Fake crown (papyrus leaf)

“Royal” cloak

Fake sceptre (stick)

Mocking homage,

Hailed as a king

Mark

Barabbas

Fake crown (thorns)

“Royal” cloak

Hit with stick, Spat on

Mocking homage,

Matthew

Barabbas

Taken to a public hall

Fake crown (thorns)

“Royal” cloak

Fake sceptre (stick)

Mocking homage

Hailed as a king

Luke

Barabbas

(No parallel passage)

John

Barabbas

Fake crown (thorns)

“Royal” cloak

Hit

Hailed as a king

Beyond the name, the two figures Jesus and Barabbas are surprisingly similar. Both supposedly were well-known within Jerusalem: implicitly Barabbas as a leader of the rebels and Jesus had his Palm Sunday following. Certain gospel verses suggest an unexpected militancy from the man of peace. It was his attack on the money-changers in the temple that finally provoked the high priests into seeking his death. Both were bound, Barabbas with the other rebels, Jesus when the high priests delivered him to Pilate. Both faced the fate of crucifixion, Barabbas because it was the necessary punishment for sedition, Jesus because it was demanded by the high priests. The similarities helped Mark to dramatise the life-and-death choice facing the Jews.

Priests behaving oddly

Conceivably, the Jewish high priests had wanted to be rid of a troublesome religious maverick. But what possible benefit would it have been to those same high priests to have had a revolutionary and murderer released back into the city? Any rebellion was certain to provoke Roman reprisal and generally speaking, the priests collaborated with the occupying power. Members of the council, a privileged elite, were a prime target of the rebels.

Conceivably, the Jewish leadership had lost the authority to execute prisoners when Rome had annexed Judea in 6 AD. Historical evidence is conflicting on this point. But, supposedly, it was not long after the demise of Jesus, in a trial sequence closely shadowing that of Jesus himself, that the “first Christian martyr” Stephen was condemned for blasphemy and immediately stoned to death.

So why wasn’t Jesus despatched in a similar fashion?

The same council that felt obliged to hand Jesus over to Pilate for execution had no such qualms about immediately stoning Stephen to death.

More theatre.

Jewish crowds behaving oddly

Up so early?

Mark reports that Jesus was crucified at 9 am, the third hour:

“And it was the third hour, when they crucified him.” – Mark 15.25

Before this time, says Mark, there had been a meeting of the whole Jewish council (elders and scribes included); they had bound Jesus and taken him across town to Pilate. Evidently Pilate was also an early riser and he immediately questioned Jesus. The Roman governor then stepped outside his praetorium in order to respond to the demands of a crowd gathering at his door. The crowd had already been instructed by the chief priests. As a result, the rebel Barabbas had been released, Jesus had been scourged and mocked in a purple cloak and crown of thorns, a whole battalion of soldiers had been assembled, and Jesus had been led out to Golgotha. All before 9 am.

Possible – but not very probable.

Only days before jubilant Jewish crowds, spreading their garments on the road, had sung Hosannas to Jesus, their “king” entering Jerusalem. Now Jesus was so hated that the Jews gather early in the morning to insist that their erstwhile king be crucified.

That’s how fickle were the Jews.

And quite what was Azazel?

In later periods Azazel was interpreted as a desolate place or as the scapegoat itself but (as the name – Azaz’ El “strong god” – suggests) originally Azazel was an evil spirit or fallen angel.

The book of Enoch (circa 200 BC) records that Azazel taught men the art of warfare and women the art of deception:

“And the whole earth has been corrupted through the works that were taught by Azazel: to him ascribe all sin.” – 1 Enoch 10:8-9.

Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman:

“The Holy One, blessed be He, commands us on Yom Kippur that we should release a goat in the wilderness, to the prince who rules over wastelands … he is its master, and destruction and waste emanate from his power … the cause of wars quarrels, wounds, plagues, division and destruction.”

– (commentary on Leviticus) 13th century

The Christian fathers saw Azazel in the darkest terms: Lucifer himself!

“... This wicked power who fell from the heavens … the cause of man’s expulsion from the divine paradise, and deceiver of the female race … the averter in Leviticus, which the Hebrew text called Azazel, is none other than he.”

– Origen, Contra Celsum, 6.43.

A Scapegoat on the “Day of Atonement”

The Jews long had a method for atoning for their sins. It involved the killing of goats. Quite how was detailed in Leviticus:

“And he shall take from the congregation of the people of Israel two male goats for a sin offering, and one ram for a burnt offering. And Aaron shall offer the bull as a sin offering for himself, and shall make atonement for himself and for his house.

Then he shall take the two goats, and set them before the Lord at the door of the tent of meeting; and Aaron shall cast lots upon the two goats, one lot for the Lord and the other lot for Azazel.

And Aaron shall present the goat on which the lot fell for the Lord, and offer it as a sin offering; but the goat on which the lot fell for Azazel shall be presented alive before the Lord to make atonement over it, that it may be sent away into the wilderness to Azazel.”

– Leviticus 16.5-10

The two goats were to be identical and thus be of equal sacrificial worth.

“The two he-goats of Yom Kippur are required to be alike in colour, in height and in value.” – Mishnah Yoma 6

One goat, chosen “by lot” by the high priest, was slaughtered immediately. Apparently, burnt flesh was a “pleasing aroma to the Lord” (Numbers 29.8). The goat’s blood was not wasted but was sprinkled about the holy of holies, copious quantities of blood also pleasing to a just and loving god. The Lord was thus able to accept the offering which atoned for the people’s sins. But only for a year.

Though atoned for, those sins had also to be carried away. This was the purpose of the second goat. By laying his hands on the animal and confessing the high priest loaded the sins of Israel onto the goat. It thus became a scapegoat which was then driven out of the city, into the desert, in fact, back to the source of sin, Azazel, and eventually to be pushed over a cliff.

After the war with Rome, and with the temple and Jerusalem destroyed, what could replace the annual Day of Atonement? Were the Jews always to be “in their sins” and separated from God? Religious radicals had an answer! Further animal sacrifice was unnecessary: Jesus had come, and had atoned for the sins of the world, in a perfect, one-off atonement, valid for all time.

“For it is impossible that the blood of bulls and goats should take away sins …

But when Christ had offered for all time a single sacrifice for sins, he sat down at the right hand of God, then to wait until his enemies should be made a stool for his feet. For by a single offering he has perfected for all time those who are sanctified.“– Hebrews 10.4, 12-14

Matthew intended to make this point much clearer than Mark had done.

Eeny, meeny, miny, moe

Kill one now, and kill the other one later

“Without the shedding of blood there is no forgiveness of sins.“

– Hebrews 9.22.

Matthew brings on the goats!

“At that time they had a well-known prisoner whose name was Jesus Barabbas. Whom do you want me to release for you, Jesus Barabbas or Jesus who is called the Messiah?“ – Matthew 27.16,17

Matthew, when he came to copying the Passover pardon passage from Mark, substituted “famous prisoner” for insurrectionist, without further detail. By so doing, Barabbas lost any negative connotations. Modern translations of ἐπίσημον often restore that negativity by using the word “notorious” but noted, notable or famous are more accurate.

Not only did Matthew remove Mark’s unwelcome indication of a link to the rebellion of the Jews but he gave Barabbas a surprising first name – Jesus! Ancient copies of Matthew (and some recent ones) read “Jesus Barabbas”, not just Barabbas. Shocked by this attachment of the sacred name to a sinner, it was soon removed by copyists: pious churchmen excised what Matthew had added. Unwilling to sully the reputation of the evangelist church father Origen insisted that the name Jesus had been added by heretics!

But Matthew had deliberately added the name Jesus to give emphasis to his own theological point: Jesus was not just a lamb but a goat! In fact, Jesus was two goats. In other words, Jesus within his person replaced and made obsolete the sacrifices of Yom Kippur.

By naming Barabbas “Jesus Barabbas” Matthew emphasized how Jesus, the true messiah and son of the father, was set against another Jesus, the son of the father, who was a false messiah.

Dead Jesus replaces dead goats

According to the Christian interpretation, the Yom Kippur ritual had been merely a foreshadowing of things to come. Retrospectively, the two sacrificial goats together could now be understood as a “type of Christ”, one Jesus to “pay” for sin, and one Jesus to “carry away” sin.

Church father Origen explained this symbolism in his Homily on Leviticus:

“You see! You have here the goat who is released alive into the wilderness, bearing in himself the sins of the people who were shouting and saying “Crucify! Crucify!” He [Barabbas] is therefore the goat released alive into the wilderness, while the other [Jesus] is the goat dedicated to God as a sacrifice to atone for those sins, making of himself a true atonement for those who believe.” – 10.2.2

The two Jesuses parallel the identical goats of the Yom Kippur sacrifice: one Jesus-goat was sacrificed for the atonement of sins. Believers thus gained life eternal. The other Jesus-goat (Barabbas) was released, bearing the sins of violence and rebellion, soon to meet death.

Where Mark’s Jesus had brought the good news of the Kingdom of God, Matthew’s Jesus propitiates sin by shedding his blood.

In Matthew’s embellished edition of Mark’s original tale, the blood-sacrifice by Jesus becomes explicit. At the last supper, where Mark had his Jesus swear a blood oath: “This is my blood of the covenant which is poured out for many” (Mark 14.24), Matthew wrote:

” This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins.” – Matthew 26.27-28

Ephesians even describes the crucified Jesus “as a fragrant offering” (Ephesians 5:2) just like the “pleasing aroma” described in Numbers for a sacrifice to Yahweh.

Again to give emphasis, Matthew adds his own contribution to the trial scene – the washing by Pilate of his hands and the acceptance by the Jews that they were eternally “covered in blood”:

“So when Pilate saw that he was gaining nothing, but rather that a riot was beginning, he took water and washed his hands before the crowd, saying, “I am innocent of this man’s blood; see to it yourselves.”

And all the people answered, His blood be on us and on our children!” – Matthew 27.24-25

Jewish guilt gets worse

Betrayal

“Judas came with a crowd” – Mark 14.43

“Judas came with a great crowd” – Matthew 26.47

“A crowd came, and the one called Judas … the chief priests, the officers of the temple police, and the elders“ – Luke 22.47,52

“Judas brought a detachment of soldiers together with police from the chief priests and the Pharisees” – John 18.2,12

Condemnation

“The chief priests stirred up the crowd” – Mark 15.11

“The chief priests and the elders persuaded the people … All the people answered, His blood be on us and on our children!” – Matthew 27.20,25

“The assembly … the chief priests, the leaders, and the people … all shouted out together … demanding he should be crucified; and their voices prevailed. ” – Luke 23.1,23

“Caiaphas advised the Jews better to have one person die for the people … The Jews replied …The Jews cried out, ” Away with him! Crucify him!“– John 18.14; 19.15

Post-mortem

Chief priests and elders gave money to the soldiers to say “body stolen” – Matthew 28.12

Joseph of Arimathea “fears Jews” – John 19.38

Luke

Luke did not follow Matthew’s anodyne “famous prisoner” description of Barabbas but in his own copying of Mark he subtly weakened what Mark had written.

“This was a man who had been thrown into prison for a certain sedition started in the city, and for murder.” – Luke 23.19

For emphasis, Luke repeated himself: Barabbas was “the one who had been put in prison for sedition and murder” (Luke 23.25). Though a subtle change, “the insurrection” had become “a certain sedition” – it would no longer unambiguously refer to the revolt of 66-73 AD.

The most radical change in Luke, however, was the complete omission of any mention of a Passover amnesty*. Luke, a more realistic author than his fellow evangelists, was doubtless aware that Roman audiences would baulk at such unexpected behaviour from one of their own military governors. The result, however, was that Luke’s crowd now behaved decidedly oddly.

In Luke’s script, after Jesus had been sent back by Antipas, it was Pilate himself who summoned “the chief priests, the leaders, and the people“. The mob had not been marshalled or primed by the chief priests but had been called together by the Roman.

The governor then told the assembled people that he has found Jesus innocent; that he intended flogging the prisoner and releasing him. In response – and quite inexplicably – the crowd spontaneously clamoured for the release of Barabbas – a call completely unwarranted by what Luke has actually written.

An insistent Jewish mob, in a single demand, made no distinction between the release of the criminal and the condemnation of Jesus. Pilate, despite his own pleas of Jesus’s innocence, was shouted down by the mob.

Luke has achieved his purpose. The entire Jewish community – “the chief priests, the leaders, and the people” – had condemned themselves as the killers of Jesus but the Roman governor had been shown to be a a fair-minded judge.

John

“This is love: not that we loved God, but that he loved us and sent his Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins.”

– 1 John 4:10

In the gospel of John the whole Barabbas episode was dealt with summarily, in just two verses. The authors retained the Passover pardon but made an important change. What had been a Roman custom in Mark and Matthew now became a Jewish custom.

“But you have a custom that I release someone for you at the Passover. Do you want me to release for you the King of the Jews? They shouted in reply, “Not this man, but Barabbas!” Now Barabbas was a robber.”

– John 18.39,40

Note that John substituted the innocuous “robber” for insurrectionist, completely losing any connection with the Jewish rebellion. John’s Pilate was completely overwhelmed by the Jews, afraid, vacillating, threatened and intimidated – and wholly fictitious.

Romans Absolved – made into witnesses to the divine truth!

Mark

“Pilate wondered … he perceived that it was out of envy” – 15.5,10

“What evil has he done? – 15.14

Inscription “The King of the Jews.” – 15.26

Pilate grants the body to Joseph – 15.45

Matthew

Pilate “wondered greatly … knew that it was out of envy” – 27.14,18

Wife’s dream of “righteous man” – 27.19

“What evil has he done?” – 27,23

Washed his hands: “I am innocent of this man’s blood” – 27.24

Centurion: “Truly this was the Son of God!” – 27.54

Pilate “ordered” body given to Joseph – 27.58

Luke

Pilate “found this man not guilty … will flog and release” – 23.13,16

Pilate wanted to release Jesus, addressed the Jews again – 23.20

A third time wanted to release …”What evil has he done? – 23.22

Centurion declares Jesus “innocent” – 23.47

“Herod and Pilate became friends … before this they had been enemies” – 23.12

John

“Pilate asked him, “What is truth?“… I find no case against him” – 18.38

Pilate again, “I find no case against him” – 19.4

Pilate a third time, “I find no case against him.” – 19.6

Tried to release, shouted down by the Jews – 19.12

Inscription “Jesus of Nazareth, The King of the Jews” in Latin, Hebrew and Greek – 19.19,20

Pilate answers Jews, “What I have written I have written.” – 19.22

Roman soldier testifies “blood and water” came out of wound – 19.34

It’s not true, it’s not history – it’s DRAMA

The custom of releasing a prisoner, chosen by a crowd at Passover, is palpable nonsense, nowhere attested outside of the gospels and historically bogus. The very existence of Barabbas is blatantly allegorical. On the one hand, he is the antithesis of Jesus, the man of peace, the embodiment of violent revolution, and a reminder of what was then recent history. On the other hand, Barabbas was a doppelgänger of Jesus himself, a foil used by Matthew to establish a parallel between Jesus “the atoning sacrifice” and the traditional ritual of Yom Kippur, made impossible by the destruction of the temple and now replaced by Jesus himself.

In this tightly written episode the complicity of the Jews was widened by successive evangelists as they redacted this episode, from envious high priests to the whole Jewish council and eventually to the entire the Jewish people. At the same time Rome and its governor were increasingly exonerated, even though they were the instrument of God’s plan, themselves becoming witnesses to the divine truth.

The historical implausibility of the Barabbas episode is beyond question. Quite simply, it was a story made up by Mark and subsequently redacted by the later evangelists.

Sources:

Schmiedel, Encyclopedia Biblica.

Hastings, Dictionary of the Bible, “Barabbas”

Raymond Brown, The Death of the Messiah: From Gethsemane to the Grave

Journal of Biblical Literature, H.A.Rigg, “Barabbas”

R.V.G.Tasker, The Greek New Testament

Bruce M. Metzger, ed. A Textual Commentary on the Greek New Testament

Resurrection or Insurrection?

And they laid hands on him and seized him. But one of those who stood by drew his sword, and struck the slave of the high priest and cut off his ear. And Jesus said to them, “Have you come out as against a robber, with swords and clubs to capture me?”

– Mark 14.46-48

“Do not think that I have come to bring peace to the earth. I have not come to bring peace, but a sword.” – Matthew 10.34

And making a whip of cords, he drove them all out of the temple, with the sheep and oxen. And he poured out the coins of the money-changers and overturned their tables.” – John 2.15

Bar Abbas – Son of the Father?

Resurrection or Insurrection?

He said to them, “But now let the one who has a moneybag take it, and likewise a knapsack. And let the one who has no sword sell his cloak and buy one.”

– Luke 22.36

“So Pilate, wishing to satisfy the crowd, released for them Barabbas.”

– Mark 15.15

“He released the man who had been thrown into prison for insurrection and murder.“

– Luke 23.25

Was Jesus really a freedom fighter or was that Barabbas?

Rather than recognise that both Jesus and Barabbas are characters in a religious fiction some scholars have reinterpreted Jesus himself as an insurrectionist.

A radical view argues that Jesus Barabbas and Jesus of Nazareth were in fact one and the same man. This Jesus had some decidedly “unpeaceful” connections. Named among his disciples were Simon the Zealot (and the Zealots were the tax rebels of Josephus’ “fourth sect”); and Judas Iscariot – arguably a member of the band of sicarii assassins (Luke 6.15,16).

This more militant Jesus, so the argument goes, was disguised by the later evangelists as a man of peace.

Unknown

In his Antiquities of the Jews, Josephus makes no mention of Barabbas nor of any Passover pardon instituted by Pontius Pilate. And yet Josephus discusses the Roman governor at length.

Did Jesus need to die?

The Son of man had “authority on earth to forgive sins” (Mark 2.10) and Jesus we are told forgave the sins of a paralyzed man (Mark 2.5), and the woman with an alabaster jar (Luke 7.48).

So why did Jesus have to die in order to redeem us from sin?

Azazel

Mount Azazel (Jabal Munttar)

– twelve miles east of Jerusalem

Azazel: in turns a demon, a desolate place, and a scapegoat.

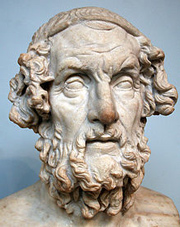

Homeric antecedent?

Dennis MacDonald (The Homeric Epics and the Gospel of Mark) identifies a scene in the Odyssey as having a telltale prototype of a “choice between two similar figures.”

MacDonald argues that Mark, like every ancient author, learned his skills by studying and emulating Homer.

A real name?

Abba appears as a personal name in the Babylonian Talmud, composed post 200 AD (e.g. R. Abba Arikha) .

“So he went after his father to the cemetery, and said to them [the dead]. I am looking for Abba. They said to him: There are many Abbas here. I want Abba bar Abba, he said. They replied: There are also several Abbas bar Abba here. He then said to them: I Want Abba bar Abba the father of Samuel; where is he? They replied: He has gone up to the Academy of the Sky.“

– Berakoth 5a.18b.22,23

“Propitiation” for sin

“For all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God, and are justified by his grace as a gift, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, whom God put forward as a propitiation by his blood, to be received by faith.

This was to show God’s righteousness, because in his divine forbearance he had passed over former sins.“

– Romans 3. 23-25

Luke Redacted

The verse 23.17 was later interpolated here: “for it was necessary for him to release to them one at every feast“.