Joseph of Arimathea

The most important removal job in history?

In one of the closing scenes of the Jesus drama a previously unheard of character is introduced. He plays a brief but vital role: he moves the body of Jesus from his cross to the tomb from which he will disappear. Without this crucial act there would be no “empty tomb” and without an empty tomb claims of a resurrection, whilst not impossible, become considerably more problematic. What, for example, would become of the body if it were still rotting on the cross, would it simply vanish while no one was looking?

In any event, this new character does move the body and with his job done, he is never heard of again *. We are speaking of Joseph of Arimathea. Later gospels will refine his character and modify his status but in Mark’s original tale he is no more than “a respected member of the Jewish council.” The man from Arimathea is credited with single-handedly retrieving the body, wrapping it in a burial cloth and placing the cadaver in a tomb which he seals shut. Joseph thereafter disappears from the Christian story.

The role is memorable for sure. But is this history – or palpable literary artifice?

“And when evening had come, since it was the day of Preparation, that is, the day before the sabbath, Joseph of Arimathea, a respected member of the council, who was also himself looking for the kingdom of God, took courage and went to Pilate, and asked for the body of Jesus. And Pilate wondered if he were already dead; and summoning the centurion, he asked him whether he was already dead. And when he learned from the centurion that he was dead, he granted the body to Joseph. And he bought a linen shroud, and taking him down, wrapped him in the linen shroud, and laid him in a tomb which had been hewn out of the rock; and he rolled a stone against the door of the tomb.”

– Mark 15.42-46

Unclean for 7 days?

“Whoever touches the dead body of any person shall be unclean seven days.” – Numbers 19.11

A tall tale draws to a swift close

It is 3 pm (“the ninth hour”). The disciples have fled, the women watch meekly “from afar” and a dead Jesus hangs on his cross. How does Mark bring his epic melodrama to a close?

Nothing happens until “evening had come,” which for Jerusalem at the time of Passover, was around 5.30-6.00 pm (a time confirmed by the gospel of Matthew in his parable of the vineyard labourers). Only now does Joseph, a member of the Jewish council, find the courage to approach the Roman governor. In so doing, in entering the Praetorium replete with its pagan imagery, he will make himself ritually impure, only moments before the Sabbath begins (which is at sunset or when three stars become visible in the night sky). So why does a respected councillor take such reckless action?

Earlier in the story we have been told that the condemnation of Jesus by the Jewish council, the Sanhedrin, had been unanimous: ” ‘You have heard his blasphemy! What is your decision?’ All of them condemned him as deserving death” (14.64).

Mark emphasizes that all the councillors were involved: “As soon as it was morning, the chief priests held a consultation with the elders and scribes and the whole council.” (15.1).

How is it possible, then, that Mark would now write that a member of the same council retrieved and disposed of the body of Jesus? At a minimum, the councillor would become “unclean” for seven days and be unable to eat the sacred Passover meal!

Sunrise/ Sunset Jerusalem

In March the sun in Jerusalem rises around 5.30-6.00 am and sets around 5.30-6.00 pm. LINK

“That evening, at sundown…” – Mark 1.32

Buried by his Enemies!

What were Mark’s alternatives? The author had already determined that the followers of Jesus had “all deserted him and fled” (14.50). The fatherless family of Jesus had long since been put aside (3.31-35). As drama, the betrayal, denial and abandonment of the Saviour intensified both the pathos of his death and the glory of the eventual confession that he was the risen Lord. But with the removal of all the other players, Mark had to create a new character to bring his drama to its grand finale.

It also made sense for Mark to invoke a high status individual for this role – anyone less would not credibly have gained an audience with the Roman Prefect – and an urgent audience at that. The “respect” that Mark says Joseph enjoyed implied that he was of orthodox behaviour and strictly observed the law, both Jewish and Roman.

In the inspirational work that Mark was working from, the book of Isaiah, the final indignity to be endured by the “suffering servant” was an ignominious burial. “They” will kill him and “they” will place him in the grave, implicitly a common grave reserved for criminals.

“They made his grave with the wicked and his tomb with the rich, although he had done no violence, and there was no deceit in his mouth … he bared his soul unto death, and was numbered with the transgressors;”

– Isaiah 53:9,12.

In Mark’s own first draft (or perhaps an earlier “passion” story that Mark was working from) the son of man was hung from a “tree” (and certainly not a crucifix) and his body was disposed of by his enemies – precisely as Isaiah “foretold”. Moreover, if such a figure as Joseph the councillor came forward asking to bury the victim a justification was to hand in Jewish scripture: Deuteronomy stipulated that a condemned man should not be left hanging on a tree overnight.

“When someone is convicted of a capital offense and is executed, and you hang him on a tree, his body shall not remain all night on the tree, but you shall indeed bury him that same day. For anyone who is hanged is under God’s curse; you must not defile your land which the Lord your God is giving to you as an inheritance.”

– Deuteronomy 21.22-23

But there was a problem. If Joseph stepped up out of religious duty, his concern for the body of Jesus would surely have to extend to the bodies of the two other criminals (“the transgressors“). Either Mark himself, or more probably a later redactor, sidled in the meaningless qualifying phrase that Joseph was himself “looking for the kingdom of God“. It was a fudge, intended to give the impression that Joseph was especially in sympathy with Jesus but avoiding the absurdity of saying that a disciple with a place on the council voted for the death of Jesus.

Shameful?

Ironically, for all the multiple redactions and harmonizations, the residue of the idea that Jesus was not buried by a fortuitously well-placed devotee with a conveniently well-placed tomb, is still to be found in Acts of the Apostles:

“Because the residents of Jerusalem and their leaders did not recognize him or understand the words of the prophets that are read every sabbath, they fulfilled those words by condemning him. Even though they found no cause for a sentence of death, they asked Pilate to have him killed. When they had carried out everything that was written about him, they took him down from the tree and laid him in a tomb.“

– Acts 13:27-29.

The words above, put into the mouth of the apostle Paul by the author of Acts, clearly attribute the burial of Jesus to his enemies (“the residents of Jerusalem and their leaders“) and not to any “Joseph of Arimathea”.

A shameful disposal, though replaced in the redacted canonical gospels with an “honourable burial”, is found elsewhere, as, for example, in the the 2nd century Apocryphon (Secret Book) of James which again relates a “dishonorable” burial for Jesus.

And that text even has Jesus himself say, “buried shamefully, as was I myself, by the evil one“.

Joseph who? A story in a state of flux

The early 2nd century Gospel of Peter introduced Joseph – not as a man of Arimathea but as “the friend of Pilate and of the Lord” – an odd band of buddies! It seems that this Joseph had been around during the ministry of Jesus: he “had seen the many good things he did.” This Joseph does indeed ask for the body, but he does so before the crucifixion not after; but at the same time, Herod assures Pilate that, in any event, the Jews would have buried Jesus in observance of their own laws.

In this gospel, Herod in fact plays a decisive role. The Jewish prince “gave Jesus over to the people” and it is the Jews, not Roman soldiers, who clothed Jesus in purple, mocked his “kingship” and put a “thorny crown on his head … some scourged him.”

“They” (the Jews) crucified Jesus and then “rejoiced”. The body was handed to Joseph for burial but remarkably, it is a whole crowd of Roman soldiers, elders and scribes who roll the stone!

“And they brought two wrongdoers and crucified the Lord in the middle of them … And they drew out the nails from the hands of the Lord and placed him on the earth … With soldiers to safeguard the sepulcher … elders and scribes came to the burial place.

And having rolled a large stone, all who were there, together with the centurion and the soldiers, placed it against the door of the burial place.“

In all this we see how, at this point in time, an alternative version of the passion narrative was in circulation, with elements of the tale rearranged. Could either version actually be “true”?

If, in reality, there had been a Jesus who had been given an honourable burial by Joseph, had could any Christian writer have invented an alternative, dishonorable burial? On the other hand, in an evolving fiction, discarding a dishonorable burial in favour of an embellished fantasy involving clean linen, a new, unused tomb, a garden setting, a vast quantity of spices, etc., would follow a rational trajectory of development of the text as the persona of Jesus became increasingly regal and deified.

In fact, it was the sensibilities of the early Christians that moved the story away from mere disposal of a corpse towards something “respectful.” The burial of Jesus by the shadowy figure of Joseph – an episode found in all four gospels – was a later refinement of the story. This development can be traced through the later gospels with the burial evolving from a pious Jew acting out of zeal for the law, to interment by a disciple of Jesus assembling the rudiments of a “royal burial.”

Arimathea? Yet another fictitious venue from the Jesus yarn

“Arimathaia is probably an invented word, meaning ‘Best Doctrine Town’ (ari- being a standard Greek prefix for ‘best’, math- being the root of ‘teaching’, ‘doctrine’, and ‘disciple’ and -aia being a standard suffix of place)”.

– Carrier, On the Historicity of Jesus, p439

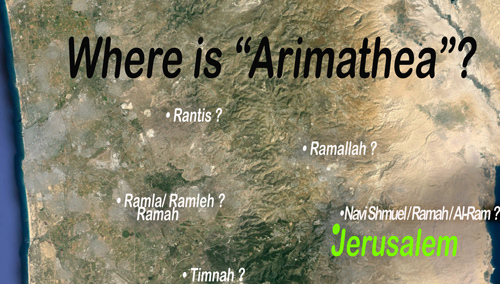

Luke weakly identifies Arimathea as “a city of the Jews” but aside from the scant gospel references, there is no record that a place called Arimathea ever existed.

Christians have never stopped guessing at a possible location for the imaginary city, seizing upon any remotely similar place name – among them Ramathaim, Ramleh, Ramah, Ramatha and Ramallah! 4th century churchmen Eusebius and Jerome argued for an identity with the supposed birthplace of the Hebrew prophet Samuel, otherwise known as Ramathaim-Zophim (itself tentatively identified with today’s Navi Shmuel). Yet even the name betrays the fantasy: Greek “Best Doctrine Town”!

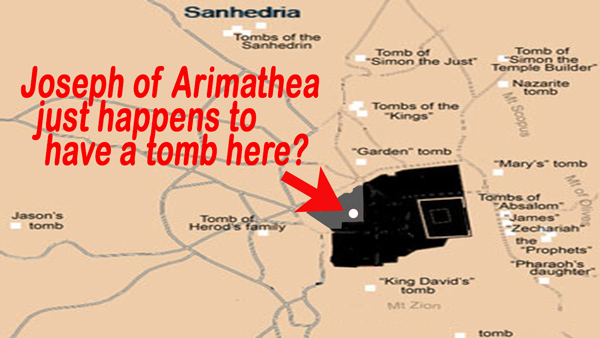

And if Joseph really came from a town of Arimathea, somehow lost to history, would not a wealthy Sanhedrist have had his family tomb in that home town, and not in the immediate vicinity of a place of public execution in Jerusalem? The fabrication is palpable

Upgrading Joe – the edit of Matthew

“When it was evening, there came a rich man from Arimathea, named Joseph, who was also a disciple of Jesus. He went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus; then Pilate ordered it to be given to him. So Joseph took the body and wrapped it in a clean linen cloth and laid it in his own new tomb, which he had hewn in the rock. He then rolled a great stone to the door of the tomb and went away.“

– Matthew 27:57-58

The author of Matthew’s gospel very effectively transformed the burial of Jesus. No longer was it the action of a devout Sanhedrist, observing the requirement of Deuteronomic law. Joseph was instead a rich disciple of Jesus, making his own, new tomb available for his dead master (and conveniently matching Isaiah 53.9, “his tomb with the rich“). No longer does Joseph have to find “courage” to approach the Roman governor (the strength of faith?) Possibly the author of Matthew recognized that Joseph could not “take Jesus down” from the cross quite so easily; he substituted for Mark’s words of permission from Pilate the prefect’s order that the body “be given” to Joseph (27.58), opening up the possibility that Roman soldiers did the work. The clutter of Pilate checking whether Jesus was “already dead” and the buying of the cloth were dropped, and Joseph after the burial tidily “went away.”

Fantasy

How likely is it that a Joseph would “just happen” to have an unused tomb closer to the heart of the city of Jerusalem than all known 1st century tombs?

How likely is it that Joseph’s pristine tomb would be only a few yards away from, facing and at the same elevation as the very spot where the Romans would execute Jesus?

Matthew deals with the closing of the tomb in a quite extraordinary way, involving a guard of soldiers deployed by the chief priests. “Burial by enemies” isn’t far below the surface.

First Matthew has to disguise the fact that the chief priests and Pharisees – in a wholly unthinkable act of uncleanliness – meet with the Roman prefect on the Sabbath day itself. He uses the bizarre circumlocution “day after the day of preparation“! Then Matthew has the Jewish holy men “remember” something Jesus has never actually said to them. Are they referring to the previous day’s testimony from false witnesses (“two came forward and said, ‘This fellow said, I am able to destroy the temple of God, and to build it in three days.‘ “) or are they harking back to the “sign of Jonah” riposte made to some scribes and Pharisees during the ministry of Jesus?

“Next day, that is, after the day of Preparation, the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered before Pilate and said, “Sir, we remember how that imposter said, while he was still alive, ‘After three days I will rise again.’ ” – Matthew 27.62-63

Did the chief priests really understand so clearly the meaning of metaphors that so completely baffled the chosen disciples of Jesus? Even more difficult to explain is how the author of Matthew could possibly have known the conversation that took place between chief priests, Pharisees and Pilate!

In any event, the priests act as if death and a closed tomb aren’t final enough. It is already the “second day” but they petition for and post soldiers standing guard – and the tomb itself is sealed: “So they went and made the sepulchre secure by sealing the stone and setting a guard.“

Matthew explains that the caution of the priests was to forestall the disciples “stealing the body and claiming a resurrection.” The inference is a clear and utterly implausible indication that Matthew’s chief priests – of all people! – feared an empty tomb, albeit a staged one. Had they already concluded that resurrection had to imply the physical body of the deceased would vanish? Perhaps a risen Jesus would have had no need of the old carcase! And why not simply round up those wretched disciples that had “forsook him and fled” (26.56)? An all-night guard was not the only way to stop would-be tomb robbers!

The story then reaches new heights of absurdity. Towards dawn on the first day of a new week, a “great earthquake” accompanies the arrival of an angel that both rolls back the stone and sits on it.

“And for fear of him the guards trembled and became like dead men …“

So now there are guards who are at least the equal to the two Marys as eye-witnesses to supernatural events – so why didn’t they join the elect and give testimony to Christ? Yes, they became “like dead men” but that was as a consequence of seeing the stone-moving angel not before. Did the divine will give them collective amnesia? Matthew says quite the opposite:

“… some of the guard went into the city and told the chief priests all that had taken place.”

So now we have chief priests, who understood clearly that Jesus spoke of his own resurrection, and had said that it would occur on that very day, chief priests who also understood that the physical body would have to disappear, presented with the evidence from several male eye-witnesses that two female followers of Jesus had turned up, a great earthquake had occurred, an angel (“like lightening“) had descended and had opened the tomb, and then they themselves had passed out?

And still the priests didn’t believe? Now that was stiff-necked!

Rather pathetically, not only do Matthew’s chief priests not “believe” in Jesus despite all the evidence, the guards who have personally just witnessed the intrusion of the divine into human affairs, are content to accept a sum of money to say they “fell asleep” and tell others that the “disciples stole the body” – and they do that risking punishment for falling asleep while on guard?! (Matthew 27.64-28.15)

Upgrading Joe – the edit of Luke

“Now there was a good and righteous man named Joseph, who, though a member of the council, had not agreed to their plan and action. He came from the Jewish town of Arimathea, and he was waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God. This man went to Pilate and asked for the body of Jesus. Then he took it down, wrapped it in a linen cloth, and laid it in a rock-hewn tomb where no one had ever been laid. It was the day of Preparation, and the sabbath was beginning.”

– Luke 23.50-54

The author of Luke’s gospel, with the stories from Mark and Matthew before him, combined and improved on the “best of both.” Luke clarified that the mysterious town of Arimathea was, in fact, “a town of the Jews” (which is, of course, no clarity at all). Luke restored Joseph to membership of the Sanhedrin but pointedly corrected Mark by saying Joseph “had not agreed” to the sentence upon Jesus. As a member of the Jewish council, Joseph is no longer a disciple but Luke updates Mark’s weasel formula: “he was waiting expectantly for the kingdom of God” (23.51) implying very strongly that Joseph was “almost” a disciple.

Luke softened the crass reference to Joseph being rich by describing him instead as “good and righteous” and Joseph’s “own new tomb” now became an anonymous tomb in which “no one had ever been laid.” Luke reverted to following Mark in crediting Joseph alone in “taking down” the body – a miracle in itself. Prudently, no reference at all was made to the Herculean task of rolling the stone to close the tomb and no credit was given to an angel for rolling it away again (the tomb is just found open as in Mark’s original version).

Not Luke, nor any other gospel writer, entertains Matthew’s ridiculous tale about the guards (or even his earthquake). For Luke “Joseph of Arimathea” is a four-line interjection, a walk-on role with no dialogue and no future.

Upgrading Joe – the mighty edit of John

A later work than the other gospels John was compiled at a time when the catholicizing cult was besting its competition. Foremost among them were orthodox Jews. The authors of the fourth gospel – the most substantial redactors of the entire body of gospel material – made major revisions to the burial sequence. Joseph was no longer identified as rich, righteous or even as a member of the Jewish council. He was a secret disciple, in fear of the Jews. But in fact, Joseph’s role was completely overshadowed by a number of innovations unique to the gospel of John.

John reprises the idea that it was the enemies of Jesus – the Jews – who wanted the body (in fact, the bodies) removed before nightfall. The authors intrude a new element into the story: not soldiers standing guard but soldiers breaking legs. Whereas in Mark Pilate had wondered if Jesus was “already dead” in John soldiers discovered that Jesus was “already dead.”

“Since it was the day of Preparation, the Jews did not want the bodies left on the cross during the sabbath, especially because that sabbath was a day of great solemnity. So they asked Pilate to have the legs of the crucified men broken and the bodies removed. Then the soldiers came and broke the legs of the first and of the other who had been crucified with him. But when they came to Jesus and saw that he was already dead, they did not break his legs.”

– John 19. 31-33

Implicit in this revised story (quite apart from all the chief priests – “the Jews” – making themselves ritually impure moments before the Sabbath!) is that Roman soldiers performed their assigned task of removing the bodies from the cross, solving the problem of just how Joseph could have done such a thing. The Romans did it for him! Joseph then took away the body, presumably left lying on the ground by the Romans. He had the assistance of Nicodemus, a leading Pharisee added to the story by the authors of John. The nearby tomb was both new and unused but no longer said to belong to Joseph. For the first and only time the tomb was said to have been located in a garden, one of several new elements lending a “respectful” gloss to the burial. Despite the Jews, Jesus was buried “according to Jewish custom,” with multiple linen cloths for his shroud and a vast quantity of burial spices provided by Nicodemus. Hinted at in the text is that the choice of tomb was provisional, chosen only because the hour was late and the tomb was “nearby.”

“They took the body of Jesus and wrapped it with the spices in linen cloths, according to the burial custom of the Jews. Now there was a garden in the place where he was crucified, and in the garden there was a new tomb in which no one had ever been laid. And so, because it was the Jewish day of Preparation, and the tomb was nearby, they laid Jesus there.” – John 19.40-42.

Like Luke, John made no reference at all to the troublesome task of rolling the stone into place but immediately moved on to the first day of the week when the stone has already been removed from the tomb.

But there are also some original and instructive new verses in John’s gospel, added before the interment:

“One of the soldiers pierced his side with a spear, and at once blood and water came out.

He who saw this has testified so that you also may believe. His testimony is true, and he knows that he tells the truth.These things occurred so that the scripture might be fulfilled, ‘None of his bones shall be broken.’ And again another passage of scripture says, ‘They will look on the one whom they have pierced.‘

After these things, Joseph of Arimathea, who was a disciple of Jesus, though a secret one because of his fear of the Jews, asked Pilate to let him take away the body of Jesus. Pilate gave him permission; so he came and removed his body. Nicodemus, who had at first come to Jesus by night, also came, bringing a mixture of myrrh and aloes, weighing about a hundred pounds. “

– John 19.34-39.

Why on earth introduce blood and water?

John’s target here was the Docetist view, an early Christian opinion that Jesus was never really a man but only appeared to be so. But in the added text the blood emphasized that the death was a “real” death and the water emphasized the “cleansing” power of the sacrifice. The multiple assurances that this was the “truth” was the surest admission that this was blatant invention!

John then refers to certain obscure phrases that were to be found in Jewish scripture that some cleric realised could be re-purposed for the Christian melodrama. Exodus gave directions for eating of the Passover meal: “you shall not take any of the animal outside the house, and you shall not break any of its bones” (Exodus 12.46). The authors of John had determined that Jesus himself was the Passover lamb therefore the injunction of Exodus applied to Jesus (forget the bit about being outside the house!) Since Jesus would die and resurrect anyway it hardly mattered if he should have had broken legs but the verse gave the opportunity to intrude another “fulfilled prophecy” into the text. Similarly, “looking on the one they have pierced” was scooped up from Zechariah 12.10., from a passage in which Yahweh himself says that sinners will turn to him in faith.

The link to Jesus is pretty tenuous – really just the word “pierced” equated to the idea of being nailed (except that nailing wasn’t even hinted at before “doubting Thomas” was added to the story. Another Johannine invention. Thomas asked to see the mark of the nails).

But hell, this is scripture, just feel the truth of it all!.

Why Mark’s timetable for Joseph is fiction

“Evening had come” (Mark 15.42)

In other words it was already almost Passover before Joseph decided to approach the Roman governor. For the Jews, days began and ended at sunset (“from evening to evening” Leviticus 23.32). There simply were only minutes between “evening” and the sunset commencement of the sabbath, yet Mark’s text indicates that the following events occurred:

1. Joseph left Golgotha, walked (ran?) to the Praetorium, asked for and gained an audience with Pilate;

2. Joseph then asked for the body, yet had to wait for a centurion to be summoned (from the crucifixion site outside of Jerusalem?) to verify that Jesus was dead (Mark 15.44-45). This meant that a messenger had to be sent from Pilate to the centurion, and the centurion himself had to return to Pilate to give his answer.

3. With permission given to retrieve the body, Joseph then left the Praetorium to buy linen in order to wrap the body of Jesus.

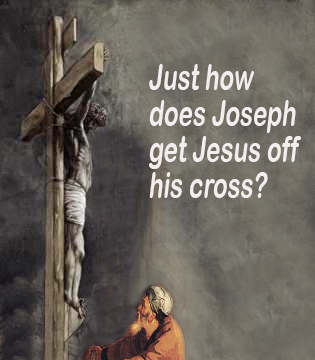

4. Joseph then returned to the site of the crucifixion where (somehow) he removed the body of Jesus from the cross – presumably a bloody body attached (by heavy nails?) to a stake. Presumably Joseph didn’t just prise the body off as if it were an animal carcass but showed some respect as to minimise further damage. Did he borrow ladders, ropes, tools, helpers?

5. The body had to be wrapped in the newly purchased linen shroud.

6. The wrapped body had then to be carried to the tomb (conveniently nearby) where Joseph laid it down (presumably with some respect, and not just dumped).

7. Finally, Joseph has to roll a substantial rock-hewn stone into place to seal the tomb.

All this before Passover? Not a chance. If any of this had ever happened it would have taken some hours, be well after dark and long into the Sabbath!

“Evening” – about 6 pm says Matthew

Matthew makes clear that even 5 pm is not yet evening!

In his parable of the vineyard workers, the last hired labourers work for 1 hour after 5 pm and before evening!

“And about five o’clock he went out and found others standing around; and he said to them, “Why are you standing here idle all day?” They said to him, “Because no one has hired us.” He said to them, “You also go into the vineyard.”

When evening came, the owner of the vineyard said to his manager, “Call the labourers and give them their pay, beginning with the last and then going to the first.” When those hired about five o’clock came, each of them received the usual daily wage. Now when the first came, they thought they would receive more; but each of them also received the usual daily wage. And when they received it, they grumbled against the landowner, saying, “These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.”

– Matthew 20.6-12

“We bury our enemies,” says Josephus

“Accordingly, our laws determine that the bodies of such as kill themselves should be exposed till the sun be set, without burial, although at the same time it be allowed by them to be lawful to bury our enemies.”

– Josephus, Wars, 3.8.5..

Body reclaim?

When Mark wrote that Joseph of Arimathea was granted permission by Pilate to retrieve the body of Jesus, the writer wasted no words explaining how the Jewish councillor might actually have performed that grisly task.

And yet removal of a body from a crucifix would have been far trickier than placing it there, especially if some dignity was to be accorded to the corpse.

Mark made no reference to the matter, commenting only that Joseph “bought fine linen, and took him down, and wrapped him in the linen.”

–Mark 15.46.

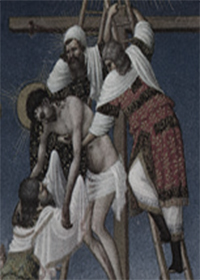

The “Descent of Christ”

Artists solve the problem of removal in various creative ways

A posse of helpers, including unidentified men leaning over the cross-bar, others with pincers, multiple ladders, sheets and ropes have all been conjured up by artists in an attempt to visualise the retrieval of JC’s body from the cross.

Yet all Mark says is that Joseph “bought fine linen, and took him down, and wrapped him in the linen.” – Mark 15.46).

Sealing the tomb would have been no less challenging: “the stone was very large” – Mark 16.4.