Arabia the Happy - Life Before Islam

The South: Arabia Felix

“Despite their physical isolation, the southern Arabs were as technically and socially advanced as any other people in the Ancient World.”

– Sitwell, p82.

Alexander the Great had been planning to circumnavigate and conquer Arabia at the time of his death. Preliminary explorations had been made of both the Red Sea and Persian Gulf.

The ‘riches’ of the southwest of the peninsular were already well-known. Despite its southerly latitude, high mountains in the Yemen, catching biannual rains, led to a very early development of civilization.

Among the first kingdoms was Saba (aka ‘Sheba’), perhaps established as early as the 8th century BC. The Sabaeans had their own script, built towns, temples, roads and, notably, outstanding irrigation works. Their capital Marib, facing the desert, was the terminus of a caravan route extending north to Petra and beyond. The trails were older, made possible by the domestication of the camel around 1200 BC.

In the 1st century BC the coastal Himyarites, with control of the sea routes, established their dominion over Saba, and over the other south Arab kingdoms during the 1st century AD. They effectively monopolized supply of both indigenous resins (frankincense and myrrh – sought after by every temple of the ancient world) and imports of spice, textiles and ivory from India and East Africa.

Understandably the country was dubbed ‘Arabia Felix’ (‘Arabia the Happy’) by the Romans, who had an insatiable demand for its exports.

Stone-built sluice gate of Marib Dam

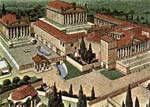

Temple of the Moon (Ilumquh) – Marib, Yemen.

Pliny records ‘Shaburah’ (Saba) as having 60 temples.

The Marib Dam

The greatest achievement of the Sabaean kingdom was a huge earth filled dam, built in the second half of the 6th century BC to hold back waters of the wadi. The dam was a quarter of a mile long and 53′ high, 200′ thick at its base. The lake that formed behind it fed a vast irrigation system, watering about 25,000 acres and supporting 50,000 people.

In the mid-6th century AD the climatic chaos which followed the catastrophic eruption of Krakatoa triggered such deluges that the dam burst on at least two occasions. The event was recorded in the Koran, where it was interpreted as God’s wrath for ingratitude:

|

Plague followed. The ruined Jewish and Arab tribes of Saba migrated north to Medina – where soon they would be exposed to a new revelation from their Lord.

Recently, the construction of a modern dam not only re-filled the ancient reservoir but also hundreds of ancient dry wells and water canals connected to it scattered through the desert. Farmland, desolate for centuries, can be used again.

Axum – The Kingdom of Abyssinia

Sometime during the first millennium BC Arabs from south west Arabia had crossed the Red Sea, married into the native Habashat tribe and established the kingdom of Axum. The second century Roman ‘guidebook’ ‘Periplus of the Erythraean Sea’ records its king Zoscales as ‘mean in his way of life but skilled in Greek letters.’

By the 3rd century AD a powerful kingdom existed, constructing palaces and monumental obelisks, trading in resins and issuing coinage. The Axumites established a presence on the Arabian coast of the Red Sea in the late 3rd century and during the 4th century extended their control over the whole of south Arabia and much of the Sudan.

Christianity arrived in Axum in the 4th century in the guise of Bishop Frumentius (a Phoenician) and, following the example set by Constantine, was given the official seal of approval by King Ezana (who none the less, continue to inscribe his monuments with pagan motifs). In 350, under its Christian king and in alliance with Rome, Axum invaded the neighbouring African kingdom of Kush and destroyed its capital of Moroe.

Following the Council of Chalcedon of 454 and the subsequent split in the Church, Axum followed the lead of Coptic Egypt and adopted Monophysite doctrines. It was the beginning of increasing isolation and decline. The Roman Empire itself was fatally weakened by the triumph of Christianity and as its power in the Red Sea region declined the main beneficiaries were Arab traders, who re-established the overland routes and ejected Axumites from most of the southwest.

Monumental Obelisk– Axum

Palace ruins – Axum

In the 6th century a king in ‘liberated’ Yemen adopted Judaism and forced conversion upon the local Christians. This provoked the Christian Axumites from across the Red Sea to re-invaded Arabia in 570, their forces stalling just before Mecca.

Their ally Byzantium installed a garrison but this was ejected when Sassanian Persia sent an army and established control over southwest Arabia.

It was at this time of confusing conflict that Muhammad was born.

The North West: Nabataea

From the 6th century BC onward the Nabataeans had moved into the region vacated by the Edomites in northwest Arabia. From their city of Petra they controlled the lucrative trade routes going north to Damascus and west to Gaza.

With the break-up of Alexander’s empire and the subsequent decline of the Seleucids, Nabataea extended its dominion as far north as Damascus, securing a lucrative monopoly of shipments out of the Arabian peninsular.

To complete its ‘cartel’ Nabataea allied itself with the suppliers, the Himyarites in the southeast of the peninsular and used its fleet to move goods north through its Red Sea port of Leuce Come – in the process eliminating the overland middle-men of Mecca and Medina.

Unsuccessful expeditions against Nabatea by Pompey (63 BC) and Augustus (26 BC) were followed by an alliance with Vespasian in 67 AD. The Nabataeans grew wealthy supplying both Romans and Persians with the riches of the east.

Rome and the Spice Trade

Rome, vexed by the cost of its imports from the east, attempted to conquer the merchant kingdoms of southern Arabia during the time of Augustus – but failed. The Nabataeans, though allied to Rome, were reluctant to give away the source of their wealth, and when pressed into service as ‘guides’ for the Roman invaders, led the legions on a debilitating march through the desert.

‘We have before related how Aelius Gallus, when he invaded Arabia with a part of the army stationed in Egypt, exhibited a proof of the unwarlike disposition of the people; and if Syllaeus had not betrayed him, he would have conquered the whole of Arabia Felix.’

– Strabo, Geography, c. 22 AD.

The Romans bided their time. By the mid-1st century AD they had learnt to exploit knowledge of the monsoon winds to eliminate the need of Arabian middlemen in the trade with India. No longer dependent upon Petran goodwill, Nabataea was annexed by Trajan in 106 AD and the kingdom replaced by the Roman province of Arabia. Ancient Petra was by-passed by a new road and supplanted by the legionary fortress town of Bostra and dwindled in importance. Non-maritime trade now shifted north, to the new boom towns of Palmyra and Hatra.

In the south the Himyarite Kingdom was also by-passed by the Roman fleet, which each year sailed directly from lower Egypt to the Malabar Coast of India. The displacement of the Yemeni Arabs in the maritime trade caused pan-arabian migration: The Banu Ghassan settled in lower Syria and founded the Ghassanid kingdom; the Banu Lakhm settled in the Kufa region, on the borders of the Persian Empire.

The North East: Syria

The Syrian Matriarchy: 4 Women (and a transvestite) who Ruled the World

Rome took possession of Syria in 64 BC, a prized and strategically vital province. In the 3rd century AD it produced a dynasty that would conquer Rome. The Syrian widow of Septimius Severus Julia Domna (mother of Caracalla) used her immense wealth to buy her grandson Elagabalus the Roman throne.

The teenage transvestite from Emesa, when he was not debauching his entourage, devoted himself to the promotion of a universal sun god religion based upon worship of a black meteorite, which he had set up in some style in a temple in Rome.

Murdered at 18, Elagabalus was succeeded by his 13-year-old cousin Alexander Severus – the youngest of all Roman emperors. But for more than a generation, real power in the Roman world rested with four ‘Oriental’ Julias – Alexander’s mother, two aunts and grandmother. Their home province of Syria, and its cities of Antioch and Baalbek, profitted enormously. The hapless Alexander was murdered in 235.

The Arab who was Master of Rome

In 244 another Syrian, Philip the Arab, became ruler of the Roman world. He was born 50 miles south of Damascus in the Roman province of Arabia. Together with his brother Priscus, Philip had risen high in the military under Gordian III and was implicated in that emperor’s assassination. When Philip got the top job Priscus ran the East.

In 248 Philip celebrated the 1000th anniversary of Rome’s foundation with spectacular games. Philip was said to have had ‘Christian sympathies’, though we know he added an octagonal forecourt to the Temple of Bacchus in Baalbek. In any event he was overthrown the following year by that early nemesis of the Christians, Decius.

Decius died in the first Roman encounter with the Goths in 251. In a period of increasing instability Valerian came to the throne in 253 only to be taken captive near Edessa (260) by Sapor, king of a resurgent Sassanid Persia. Antioch was sacked and Roman Mesopotamia occupied.

The First Arab Empire – Palmyra, 260-272 AD

In the mid-3rd century the Romans were unable to eject Persian invaders from their rich eastern provinces so the job was accomplished by their client king Odaenathus (Septimus Odeinat), sheikh of Palmyra, using heavily-armed cavalry (‘cataphracts’).

After Odaenathus’s assassination his wife Zenobia (ruling in the name of her young son Vaballathus) extended the kingdom far into Roman Asia and Egypt and formed alliances with Armenia and Persia.

The Palmyrenes (ethnically semitic Amorites and Arabs) adopted many elements of both Greco-Roman and Parthian-Persian culture.

The breakaway empire was teeming with large cities, rich with industry – textiles, glass, metal, and leather-working. Palmyra itself profited from east-west trade.

Palmyra never recovered from Aurelian’s vengeance of 273, after almost four years of battles and sieges.

Zenobia – Arab Queen with Attitude. She declared herself ‘Augusta’ in 270. Aurelian paraded her in golden chains in his Roman triumph but allowed her to retire to Tivoli. Apparently she made quite a hit on the Roman social scene.

After Zenobia’s rebellion Palmyra became increasingly militarised and less important as a trading centre.

Bastion of Paganism: Baalbek – Sun City

At Baalbek the sun god – Baal/Hadad/ Roman Jupiter – was honoured as part of a trinity with Artagatis/Astarte, Roman Venus, a fertility goddess and Adonis/Hermes/ Roman Mercury, a young god of spring and renewal.

Roman policy was to rebuild the sanctuary on a truly monumental scale, demonstrably integrating the new province and its devout Oriental population into the imperial system. So successfully was this accomplished that the ‘Heliopolitan Triad’ spread throughout the Roman Empire. Evidence of the gargantuan building effort is to be found in a nearby quarry where, unfinished, is the largest cut stone in the world, all 1200 tons of it. (Subsequent Roman gigantism was achieved with poured concrete.)

The vast complex of temples eventually covered some 16 acres. The Temple of Jupiter – largest in the Roman world – housed a famous oracle, apparently expressed through the movements of a statue of the god, animated by shaven-headed priests.

Then …

Baalbek – Sun City

The sacred city of Baalbek (aka Heliopolis ) began as an ancient Phoenician settlement on the trade route northwest of Damascus. It remained a major centre of pilgrimage and paganism throughout the Byzantine Christian era despite severe and repeated persecution.

Building activity at Baalbek came to a halt when Constantine declared for Christianity – and destruction began.

Now …

Demolition Man

‘Hearing that some of the inhabitants of Phoenicia were addicted to the worship of demons, John selected some ascetics who were filled with fervent zeal and sent them to destroy the idolatrous temples, inducing some ladies of great opulence to defray the monks’ expenses; and the temples of the demons were thrown down from their very foundations.’

– Bishop Theodoret of Cyrrhus (393-466) expresses his admiration for John Chrysostom’s demolition teams (‘Historia Religiosa’)

Hagia Sophia (Istanbul)

Imperial Vandal

Justinian ordered Syria’s pagans to accept baptism under penalty of confiscation and exile.

To make his point he had 8 of the gigantic columns (8′ thick, 65′ high) shipped to Constantinople to hold up his big church – Hagia Sophia.

Other columns were pillaged from the Temple of Artemis in Ephesus, and from monuments in Rome.

During the Seleucid period it seems evident that the ancient fertility cults (and their rites of sacred prostitution) were giving way to mystery cults in which the idea of a personal resurrection was gaining ground. Reflecting this trend towards a mystical rebirth, a Temple of Adonis/ Dionysus/ Roman Bacchus was added to the complex during the reign of Antoninus Pius (138-161).

But Christianity made little inroad here. Building activity and state patronage came to halt when Emperor Constantine declared Christianity the official religion in 330. Constantine forbade the ‘licentious pagan practices’. The fanatic Theodosius had the tower-altar, which stood 18 meters high facing the entrance to the Temple of Jupiter – a sort of ‘holy of holies’ accessible only to the priests – knocked down, and the surrounding statues demolished. With the rubble he had a cathedral built within the temple precinct.

Purge followed purge throughout the 6th century but with little effect. Tiberius Constantine (578-582) ordered the burning of five pagan priests along with their idolatrous writings; remaining intransigent pagans were to be punished by the fury of the army. And yet:

‘Baalbek was still active as a cult centre at the death of Emperor Maurice in 602 AD, and continued to flourish as a pagan centre well into the early Islamic period.’

– Dalrymple, p263.

The early Arab invaders converted the temples into fortresses (re-using ancient columns in a mosque). Subsequently what remained of Baalbek suffered from bitter fighting and sieges for centuries until final desolation in the 16th century.

Sources:

W. Cook & R. Herzman, The Medieval World View (OUP, 1983)

John Gribbin, Science a History (Penguin, 2003)

William Dalrymple, From the Holy Mountain (Flamingo, 1998)

Ira Lapidus, A History of Islamic Societies (CUP, 2002)

N. H. H. Sitwell, Outside the Empire-The World the Romans Knew (Paladin, 1984)

Edward Gibbon, Decline & Fall, Chapters 50-52 The Coming of Islam, Arab Conquests

M. Brett, W. Forman, The Moors, Islam in the West (Orbis, 1980)

Justin Wintle, History of Islam (Rough Guides, 2003)

J. Bloom, S. Blair, Islam – Empire of Faith (BBC Books, 2001)

J. J. Norwich, Byzantium, The Early Centuries (Viking, 1988)

C. McEvedy, The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History (Penguin, 1987)

Robert Marshall, Storm from the East (BBC Books, 1993)

The Spice of Life

Spice routes between India and the Middle East were very ancient, favouring the early development of both southeast Arabia (Oman/ Salalah-Khor Ruri) and southwest Arabia (Yemen/Cana, Muza).

Black pepper, ginger, nutmeg, and cloves came from India and the East.

Sacred Perfumes

Aromatic perfumes, incense and fragrances were a staple commodity of the trade routes.

Frankincense (‘Frankish, hence superior, incense’), was much sought after by the churches of Christendom – despite originating with the infidel.

Another resin, myrrh, also originated in south Arabia/Horn of Africa, as did cinnamon.

Arab trade cartel that vexed Rome – 1st century BC to 2nd century AD.

Demand in the Mediterranean world was for resins, spices, ivory, ebony, and pigments. Going east was little more than gold.

Saffron. The world’s most expensive spice, originating in India and Persia.

The word saffron entered nearly all European languages from Arabic ‘za’faran’.

Jasmine, from Arabic/Persian ‘Yasmin’, useful medicinally (and supposedly as an aphrodisiac).

Originating in China, it was introduced into Spain by the Moors. Similarly, sandalwood derives from Arabic ‘sandal‘.

Kingdoms of the Yemen

Camphor (aka ‘gum arabic’) – ‘the favorite scent of Mohammed’

On the Spice Road: Baraqish (Yathul) – Minaean capital

Rome Conquers ‘Arabia’

In the early 2nd century AD Rome absorbed most of Nabataea. A frontier road through the new province of ‘Arabia’ by-passed Petra, sealing its fate.

With an annual fleet sailing directly from Egypt to India, Rome was able to eliminate the long, expensive and hazardous trade routes that passed through Arabia’s deserts and oases.

Julia Domna – daughter of a priest of the sun god Elagabal, fan of the sage Apollonius of Tyana.

Committed suicide when Caracalla was assassinated.

“Philip, an Arab by birth, and consequently, in the earlier part of his life, a robber by profession.“

– Edward Gibbon

Trinity – Palmyra-style.

Eastern front

Rome’s Eastern Front circa 600 AD.

Both Rome and Persia used ‘Christian’ Arab tribes to guard the caravan routes from marauding Bedouin and fight as mercenaries.

Byzantium’s withdrawal of payments to the Ghassanids pulled away an essential prop of their empire in the Levant.

Getting Down to Business

When the Arabs took Alexandria in 641 they became the major player in the spice trade.

When the Persian Gulf fell into their hands shortly afterwards theirs was a monopoly of east/west trade. Islamic merchants controlled the spice routes for centuries.