When the Parthian king Pacorus II died in 105 two claimants emerged to fight for the throne – Osroes I in the west of the empire and Vologases III in the east. The civil war dragged on for nearly a decade and in 113, in a bid to outflank his rival, Osroes installed his nephew Parthamasiris on the Armenian throne. However the move contravened the Neroian settlement between Parthia and Rome (which gave “coronation rights” to the Roman emperor) and Osroes had underestimated the reaction in Rome. His intervention in Armenia provided Rome with a pretext for war at a time when the emperor already had designs on the east.

Rejecting Parthian peace envoys while passing through Athens, Trajan arrived in Antioch early in 114. Here the army of the east, strengthened by units drawn from across the empire, was being marshalled by Hadrian – some eleven legions in all. In the spring the army moved up to the Cappadocian fortress city of Melitene and crossed into Armenian territory. Armenian resistance was light and ineffective and the legions soon took Arsamosata and reached the town of Elegeia. Here Trajan, before the audience of his legions, refused the obeisance of Parthamasiris, ended the ‘Arsacid’ monarchy (later restored) and annexed Armenia into the Roman empire.

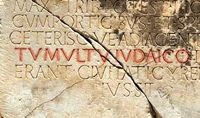

Nisibis – a Jewish treasury

Late in that campaign season Roman troops moved south from the Armenian highlands with a strategic objective in focus – the fortress city which guarded the trade route through northern Mesopotamia – Nisibis. This city, “Antioch in Mygdonia” and erstwhile Armenian southern capital, was at the time under the control of Adiabene, a Jewish client kingdom of Parthia, further east. Jews had been a major element of the population of Nisibis ever since their “Babylonian exile” in the 6th century BC. Reports Josephus:

“There was also the city Nisibis, situate on the same current of the river. For which reason the Jews, depending on the natural strength of these places, deposited in them that half shekel which every one, by the custom of our country, offers unto God, as well as they did other things devoted to him; for they made use of these cities as a treasury, whence, at a proper time, they were transmitted to Jerusalem; and many ten thousand men undertook the carriage of those donations, out of fear of the ravages of the Parthians, to whom the Babylonians were then subject …

Now the whole nation of the Jews were in fear both of the Babylonians and of the Seleucians, because all the Syrians that live in those places agreed with the Seleucians in the war against the Jews; so the most of them gathered themselves together, and went to Neerda [Neardea] and Nisibis, and obtained security there by the strength of those cities; besides which their inhabitants, who were a great many, were all warlike men. And this was the state of the Jews at this time in Babylonia.” – Josephus, Antiquities 18.9.

Other Roman units took the ancient capital of Artaxata. As the campaign season grew to a close an imperial legate and procurator set about organizing the new Roman province of Armenia. Trajan himself returned to Antioch in triumph after an almost bloodless victory.

” When Trajan had invaded the enemy’s territory, the satraps and princes of that region came to meet him with gifts. One of these gifts was a horse that had been taught to do obeisance; it would kneel on its fore legs and placed its head beneath the feet of whoever stood near.”

– Dio Cassius, Roman History, 68.

In the spring of 115, with a massive Roman army gathering in Armenia ready to invade Parthia’s client kingdoms of northern Mesopotamia, the worried local monarchs of Edessa (Abgar VII), Batnae-Anthemusia (Sporaces) and Singara (Mannus) sent their pleas to Trajan. The conqueror’s response was to dismiss the envoys and organize the petty kingdoms of Osroene into a new Roman province of Mesopotamia. Nisibis became the capital of this new imperial possession. Trajan’s forces moved south and entered the city of Singara, a largely Arab city, without a fight.

Aware that a treeless waste awaited the legions as they ventured deeper into Parthian territory, Trajan sent his troops into the forests of eastern Osroene where they cut the timber for an armada of prefabricated ships. Moved by wagon onto the Tigris, these transports completely surprised the Parthians who fell back and refused to confront the invader.

The war was going spectacularly well.

“The Jewish commercial element is further represented by the merchant Ananias who is found proselytizing at Spasinou Charax, the chief port for the Indian trade on the Persian Gulf in the middle of the century. It may therefore be legitimate to see the Jewish traders as already active in the import and transfer westward of oriental wares (silk, spices, condiments, precious woods, etc.) which flourished throughout the ancient period, and whose chief stations in Babylonia, Mesopotamia and Adiabene were Seleucia on the Tigris, Nisibis, Singara and Edessa. At all these places Jewish communities were to be found.”

– Shemuel Safrai, M. Stern, The Jewish People in the First Century, p725.

The assault on the Parthia heartland was delayed because a major earthquake struck Syria in December 115. Antioch was particularly badly hit. Many thousands were killed, including a consul and troops assembling for the impending war. Even Trajan’s own residence was wrecked. In later years, Christian inventiveness would link the earthquake to the fabricated celebrity martyrdom of bishop Ignatius, supposedly accused by the pagans of having caused the quake!

But in 116 the Roman armies struck south in two columns, one following the course of the Euphrates and the other the Tigris. Again, Parthian forces melted away.

On the eastern flank, the Romans forces first crossed into Adiabene, capturing Gaugamela and Arbela, the capital. Adiabene was the kingdom which had embraced Judaism a century earlier during the time of Izates and his mother Helena. In 66-70 the kingdom had given support to the forces fighting Rome in Judaea. At this juncture Adiabene had dynastic links with another Parthian subject kingdom Characene which controlled trade access on the Persian Gulf. Adiabene disappeared into Roman “Assyria”. The province would last barely two years. However the Christian church which shortly emerged in Adiabene called itself – and even today continues to do so – Assyrian.

“After capturing Ctesiphon Trajan conceived a desire to sail down to the Erythraean Sea.”

– Dio Cassius, Roman History, 68.

On the western front Roman forces followed the valley of the Euphrates, They soon reached Seleucia, a city which rivalled in wealth and population Alexandria in Egypt. The city offered little resistance. Trajan then crossed the narrow neck of land to the Tigris and encircled the Parthian winter capital of Ctesiphon, which capitulated after a short siege.

The emperor, at this high point hailed by the Senate as “Parthicus”, moved on, receiving the submission of the king of Characene at Mesene, an island in the Tigris. Standing on the shore of the Persian Gulf, Trajan famously regretted that, but for his age, he would have gone on to India. In the words of Edward Gibbon, Trajan “enjoyed the honour of being the first, as he was the last, of the Roman generals, who ever navigated that remote sea.”

Turning north to Babylon the Roman emperor offered sacrifice in the very room where Alexander the Great had died 400 years earlier – and no doubt savoured his own eternal glory. The campaign’s success appeared to be complete and spectacular.

“Palmyrenes, Jews and others profiting from the border traffic suffered a major setback when Trajan abolished the border and moved it to the Persian Gulf. In addition, of course, the Jews had other reasons to hate the Romans.”

– Jan Retső, The Arabs in Antiquity, p436

In fact, Trajan’s lightning triumph was an illusion. The Parthian king Osroes remained undefeated and had fled east before the advancing Romans. Now, everywhere along a front of 600-miles, the Parthians were able to harass the invader from foothills east of the Tigris. Roman supply lines were dangerously exposed and the fortress of Hatra, bypassed by the legions, became a focus of resistance.

At this anxious moment news reached Trajan that in regions as far afield as Cyprus, Egypt and Cyrenaica (Libya) the Jews were in revolt, encouraged by Jewish agents sent from Parthia and the depletion of the local military. In Cyprus, where Herod the Great had owned copper mines, Jewish rebels were agitated by a local messianic pretender ‘Artemion’ and had forced Greek and Roman citizens to fight each other in gladiatorial combat. Cyrenaica was even more badly hit and the slaughter of Greek settlers had been horrendous. A Jewish messiah, ‘King Lukuas’ had been proclaimed, pagan sanctuaries and the Caesareum had been attacked and Cyrene itself almost destroyed. 4th century Christian historian Paulus Orosius records that the violence so depopulated the province of Cyrenaica that new colonies had to be established by Hadrian.

“The Jews … waged war on the inhabitants throughout Libya in the most savage fashion, and to such an extent was the country wasted that its cultivators having been slain, its land would have remained utterly depopulated, had not the Emperor Hadrian gathered settlers from other places and sent them thither, for the inhabitants had been wiped out.”

– Orosius, Seven Books of History Against the Pagans, 7.12.6

The rebels had careened along the coast, causing carnage in Alexandria and inciting revolt in Judaea. A widespread uprising centred at Lydda threatened grain supplies from Egypt to the front.

Worse yet, the Jewish insurrection spread to the recently conquered provinces. Cities with substantial Jewish populations – Nisibis, Edessa, Seleucia, Arbela – had joined the rebellion and slaughtered their Roman garrisons. The Romans were now obliged to attack cities which less than two years before had fallen so easily into their hands. Units were rushed north, under the command of Lucius Quietus, Trajan’s cavalry commander. The city of Edessa, most threatening to the province of Syria and the fate of the entire army in Persia, was brutally sacked. Quietus moved so decisively in suppressing Jewish revolts across the new provinces that Trajan set him the same task in Judaea. The Jews would subsequently corrupt his name Quietus into “Kitos” and call the revolt of 115-117 the “Kitos war”.

Land, sea and cavalry forces, and another leading general Quintus Marcius Turbo, had to be released from the Persian front to suppress the Jewish rebellions in Egypt and Cyrenaica. Hadrian was assigned the task of pacifying Syria and Cyprus. Such was the hatred felt towards the Jews on that island, that they were, on pain of death, forbidden to set foot “even if shipwrecked.”

“There were peals of thunder, rainbow tints showed, and lightnings, rain-storms, hail and thunderbolts descended upon the Romans as often as they made assaults. And whenever they ate, flies settled on their food and drink, causing discomfort everywhere. Trajan therefore departed thence, and a little later began to fail in health.”

– Dio Cassius, Roman History, 68.

Abandoning any designs that he may have had of annexing Parthia, Trajan offered the local population a king of their “own”. Parthamaspatas, a son of Osroes who had spent much of his life in exile in Rome, had been brought on the expedition as part of the emperor’s entourage. He now proved useful:

“Trajan, fearing that the Parthians, too, might begin a revolt, desired to give them a king of their own. Accordingly, when he came to Ctesiphon, he called together in a great plain all the Romans and likewise all the Parthians that were there at the time; then he mounted a lofty platform, and after describing in grandiloquent language what he had accomplished, he appointed Parthamaspates king over the Parthians and set the diadem upon his head.”

Retreating northward Trajan took personal command of the ineffectual siege of Hatra. Throughout the summer of 117 the siege continued to drain away Roman resources. But the 5-miles of walls did not yield. Then the emperor himself suffered heatstroke and began the long journey back to Rome. Sailing from Seleucia, the emperor’s health deteriorated rapidly. He was taken ashore at Selinus in Cilicia where he died.

Hadrian received the news of Trajan’s death in Antioch. It was scarcely a moment for celebration. His most pressing task was to extricate himself and the army from a hopeless military adventure. Hadrian took the unpopular but farsighted decision not only to end the war but also to abandon Trajan’s eastern conquests.

Hadrian’s “exit strategy from Iraq” retained only a minor compensation for Rome’s wasted Herculean effort. Although he abandoned the erstwhile province of Mesopotamia he installed Parthamaspates – ejected from Ctesiphon by the returning Osroes – as king of a restored Osroene. A Roman client state would now protect the Syrian flank.

For a century Osroene would retain a precarious independence, sandwiched between two empires. In that period it would incubate a novel creed – Syriac Christianity – out of the ruins of Edessa. It would also produce the first Christian monarch when Abgar IX (179-186) gave state sponsorship to a devotion which wrapped divine endorsement around his precarious earthly authority. The device would be copied by the client kings of Armenia – and soon after by Constantine, Emperor of Rome.

“The crushing of this widespread Jewish sedition marked the demise of that flourishing Jewish centre for centuries to come … a bloodbath of immense proportions did indeed occur.”

– Oded Irshai (The Illustrated History of the Jewish People, p61)

Decimated by Roman troops deployed in the Jewish quarters, with their urban and religious organisation shattered, remnants of Egyptian Jewry metamorphosed into embryonic Christians (‘… in the eyes of the local Greeks, Christianity was just another brand of Judaism.’ – Irshai).

Notable among them was a young man – he would have been about eighteen at the time of the insurrection – studying in the very city of Alexandria and witness to the carnage: Valentinus. Another was Basilides.

Following in the tradition of synthesis and syncretism of long-standing in Alexandria (e.g. Philo a generation earlier), these ‘proto-Christian theorists’, Valentinus and Basilides competed against each other, had their own cult followings, and produced their own ‘gospels’. And then …

“Mark”: Bringing the Celestial Superjew Down to Earth

It is intriguing to note that two proto-Christian theoreticians Ignatius and Saturninus had been in Antioch at the same time as Hadrian. And lo! and behold, a revised gospel was to subsequently appear:

“Matthew” – A Gospel for Messianic Jews

Hadrian moved his court to Alexandria. The Jews of Jerusalem sent a delegation to him, led by the aged priest Akiba, but to little avail. Hadrian despised the Jews for their insularity and arrogant claims for a single concept of the divine. Their treachery in the recent war had hardened his contempt. One of his first acts as emperor in 118 was to promote the pacifier of the Jews of Egypt, Quintus Marcius Turbo, to the key governorship of Pannonia and Dacia. For twenty years there would be hostility between the enlightened Roman monarch and the zealots of Jehovah – with consequences beyond imagination.