Caesarea – A City Built by Hadrian

Where Jesus Never Trod

Herod’s trademark city of Caesarea actually owes more to Hadrian than it does to the Jewish king. Within seven years of the city’s inaugural games Herod was dead and a decade later his kingdom was itself in pieces, the greater part reorganized as a minor Roman province governed from the harbour city.

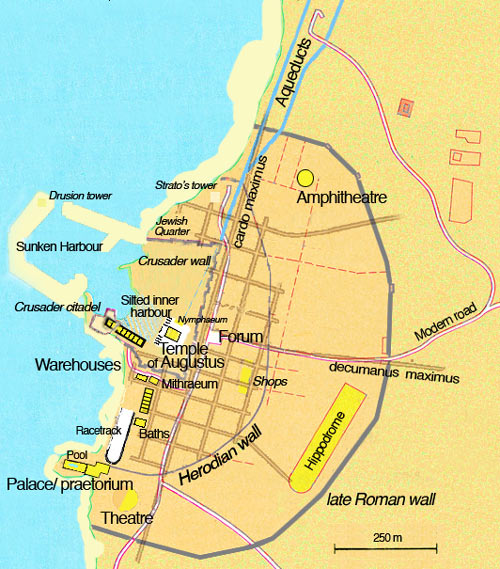

The destruction of Jerusalem in the first Jewish war emphasized the importance of Caesarea as the economic and political hub of province Palaestina, and that predominance was elevated further after the Bar Kochba war, waged during the later years of Hadrian (132-136). Though in the popular mind overshadowed by the Herodian foundation, in fact both the city and the harbour of Caesarea were extensively rebuilt by the Roman emperor. The Hadrianic city extended far beyond the Herodian centre and had no defining city wall for more than 300 years.

At its height the city covered an urban area of nearly a thousand acres – almost five-times the size of Jerusalem.

Caesarea

Coastal settlement

In his travels Herod had seen for himself the achievements of Rome. By employing the latest technologies of Rome – particularly hydraulic concrete and massive artificial breakwaters – Herod saw a way to give his kingdom a trading port on an unpromising stretch of Mediterranean coast. Eight years later work began.

Caesarea – Herodian beginnings

“So this city was thus finished in twelve years; during which time the king did not fail to go on both with the work, and to pay the charges that were necessary.”

Impressive as the harbour was, the civilian city beyond the port began to develop only after Herod’s death in 4 BC and especially after Caesarea was chosen as the seat of the Roman prefects and headquarters of the 10th Legion, early in the 1st century.

Caesarea – a Roman garrison city

As residents of a thoroughly pagan metropolis, the frustrated Hellenized Jews, least in sympathy with the messianic dreams of Jewish fanatics, were pushed closer to the revolutionary aims of the zealots. Like that other great entrepot of the eastern Mediterranean, Alexandria, Caesarea became the scene of racial and cultural conflict. As the Talmud itself recognized, coexistence of the Jewish and Roman ways of life was “impossible.”

Caesarea – a war capital

“The ostensible pretext for the war was insignificant in comparison with the fearful disasters to which it led.”

“As if divinely ordained, the inhabitants of Caesarea massacred the Jews who lived there; in less than an hour more than 20,000 were slaughtered and Caesarea was wholly deprived of Jews, for even the fugitives were seized by Florus and sent in chains to the dockyards.”

“For the number of those who perished in combats with wild beasts, or in fighting each other, or by being burned alive exceeded twenty-five hundred. Yet all this seemed to the Romans too light a penalty, though their victims were dying in a myriad of ways.”

With the total destruction of the rival city of Jerusalem in 70 AD, Caesarea entered its most prosperous era.

Hadrian in Caesarea – a Roman metropolis

“If someone tells you that Jerusalem and Caesarea are both flourishing or that both cities are destroyed, do not believe it. But if he says that one is flourishing and the other is destroyed, believe it.”

From the evidence of the theatre and elsewhere, “Herodian” materials were reused in the construction. Along the shoreline, Herod’s ancient racetrack was shortened and redeveloped as an unusual elongated amphitheater, with double the original seating capacity. The governor’s headquarters, the praetorium, was refurbished and extended fifty metres further east. A new pier was attached to the earlier, Herodian structure, to inhibit silting up of the inner harbour. A huge new hippodrome (circus), 460-metres long, was built inland to the east and was the venue for races that became famous throughout the Roman world. A second amphitheatre was added on the north side of the town. One of the many warehouses (horrea) from the Herodian period was redeveloped as a Mithraeum, doubtless to meet the religious needs of the military. To supply the city’s larger 2nd century population, engineers of the 10th Legion tapped into a new water source, the Tanninim (Crocodile) River, running underground piping for four miles and then attached a second aqueduct to the first built by Herod a century earlier.

Decline and Fall

Several times the town changed hands between Muslims and Christians, precipitating a steady desertion of most of the population. When the harbour finally silted up the Crusader settlement shrank to little more than a citadel built on the southern breakwater. Caesarea eventually disappeared under swamp and sand dunes.

PS: "The Holy Grail" – Made in Caesarea!

In May 1101 Crusaders from Genoa captured Caesarea and pillaged the small Islamic town. Among the booty that fell into their hands was a particularly fine hexagonal green dish taken from the mosque. The invaders were largely ignorant of glass-making and imagined that the dish had been carved from a giant emerald! Thus valued, the “gem” was used to pay their creditors back in Italy.

The dish in reality is early Islamic glassware. The Romans had been outstanding glass-makers and the skill had not been entirely lost in the Muslim world.

- Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 15; Jewish War I.

- Avner Raban, Kenneth Holum, Caesarea Maritima – A Retrospective after Two Millennia (Brill, 1995)

- Eusebius, The Martyrs of Palestine (Digireads, 2005)

- Ehud Netzer, The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder (Baker, 2008)

- Lee I. Levine, “Roman Caesarea: An Archaeological-Topographical Study.” Qedem II, 1975

- Lee I. Levine, Caesarea under Roman rule (Brill, 1975)

- M. Grant, Herod the Great (McGraw-Hill, 1971)

- Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land (OUP, 1986)

Sunken harbour

Metropolis

Water sports

Hadrian at Caesarea

Hadrian in the New Testament?

As 4th century churchman Jerome tells us, a statue of Hadrian, seated on horseback, was erected on the levelled platform of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount after the defeat of Jewish rebels in 135 AD.

Emperor Hadrian upgrades Herod's aqueduct

Left channel, the aqueduct of Herod. Right channel, the aqueduct of Hadrian.

Herod's theatre remade as Amphitheatre by Hadrian