Elaboration of a myth

Neither Mark nor Paul, nor any of the other writers of the New Testament letters, know of Jesus’s birth to a virgin; in fact, they show no awareness of his nativity at all. Though collectively all are earlier writers than Matthew and Luke, they evidently know least about his birth. Perhaps even more surprising, the authors of John, though certainly aware of the birth tales presented by Matthew and Luke, have passed over those stories as unworthy of a mention in their own gospel. But for all that, the pretty tale of miraculous birth and fulfillment of ancient prophecy has delighted and enthused generations of Christians who, with simple faith, are able to weather the harsh storm of rationality and objectivity with a halfwit’s beaming smile.

Hey, it’s Christmas.

No nativity yarn in Epistles, Mark or John!

In the letter to the Galatians, the writer of this particular Pauline epistle stresses one point about the birth of the Christ – and it is not the extravagant claim that he was born to a virgin. It is the rather prosaic claim that the birth conformed with Jewish Law (in other words, that Christ was born a Jew):

“But when the time had fully come, God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under law.”

– Galatians 4.4.

The only other occasion where the Pauline writers are at all concerned with the birthing of Jesus is Romans 1.1-3. and here the reference is to “human seed”, not the agency of divine spirit:

“I Paul, a servant of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle and separated onto the gospel of God …concerning his Son Jesus Christ our Lord, which was made of the seed of David according to the flesh.”

The author of Mark is another who has no story of a holy virgin or divine impregnation. Mark’s Jesus makes his first appearance as an adult, not a child, and there is no later referral to any supernatural, or even natural, birth. Mark sketches in the barest detail regarding his hero’s origin. His Jesus came “out of Galilee”, emerging from the city of Nazareth for his baptism by John. But that is all Mark has to say on the matter.

Perhaps more telling is the treatment of Jesus’ origin in the gospel of John. Here, the author, though he almost certainly knew the earlier fables dreamed up Matthew and Luke, like Mark, has no interest in any human genesis of his “Word of God made flesh”. John states very clearly that Jesus was “the son of Joseph” (John 1.45; 6.42.) – which could hardly have left Mary a virgin. Again, like Mark, he prefaces his story of Jesus with a preamble about John the Baptist and when the “Light” and the “lamb” first appears it is as an adult. Later in his gospel, John’s Pharisees discuss the Christ and they are clearly under the impression that Jesus had no connection with Bethlehem (John 7), a belief shared earlier in his tale by the soon-to-be disciple Nathanael. Not even the evangelist John is sold on the fantastical “virgin birth” yarn!

Fulfilled Prophecy? No, just cut and paste

All this took place to fulfil what the Lord had spoken by the prophet:

“Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call his name Emmanuel. ” – Matthew 1.22-23.

“Butter and honey shall he eat, that he may know to refuse the evil, and choose the good. For before the child shall know to refuse the evil, and choose the good, the land that thou abhorrest shall be forsaken of both her kings.” – Isaiah 7.15-16.

When Hezekiah inherited the throne a few years later it was at the height of Assyrian expansionism. The early years of his reign witnessed a rebellion by the northern kingdom under Hoshea, which provoked the wrath first of Shalmaneser V and then of his successor Sargon II. As a result, the northern kingdom, based on Samaria, was destroyed in 721 BC and much of its population (“the lost ten tribes”) deported.

Though in vassalage to Assyria, Judah gained emigre priests from the north, whose presence at the royal court strengthened the hand of the Yahwehists and prompted religious “reform” and notions of resistance. And indeed, following Sargon’s early death, and in collusion with Egypt, Hezekiah found the courage to rebel, and launched attacks against neighbouring Assyrian allies. At this juncture, propaganda highlighting the king’s “favour in the eyes of the Lord” became apposite to Judah’s very survival and “Isaiah” got to work.

“With the acknowledgement of Assyrian overlordship, and the attendant recognition of Assyria’s gods, the theological foundations of the monarchy – Yahweh’s eternal choice of Zion and David – were thrown into question.”

Quite simply, the “prophecy of a virgin birth fulfilled in Jesus”, although repeated a million-fold in every nation that ever succumbed to the psychosis of Christianity, is pious rubbish from beginning to end.

A Census? Straight from the pages of Josephus

“And it came to pass in those days that a decree went out from Caesar Augustus that all the world should be registered. This census first took place while Cyrenius was governing Syria. So all went to be registered, everyone to his own city.” – Luke 2.1-3.

“Now Cyrenius … came at this time into Syria … being sent by Caesar to he a judge of that nation … Cyrenius came himself into Judea, which was now added to the province of Syria, to take an account of their substance, and to dispose of Archelaus’s money;”

– Josephus, Antiquity of the Jews” – 18.1.1-3.

“And Joseph also went up from Galilee, out of the city of Nazareth, into Judaea, unto the city of David, which is called Bethlehem; because he was of the house and lineage of David: To be taxed with Mary his espoused wife, being great with child.” – Luke 2.4-5.

The nonsense of such a proposition is palpable. The tale also illustrates how the author of Luke was heavily dependent on the work of Josephus for his “historical accuracy”. Josephus provided Luke with all the tidbits he needed about the registration in Judea of 6 AD for him to construct the brief preamble to the nativity tale. But even Josephus does not vouch for a “worldwide” registration and neither does anyone else.

An earlier census? – Not according to Luke!

Never able to concede gracefully, Christian apologists devote a lot of energy to rescuing Luke from his chronological errors by manipulation of both the text and historical evidence. Thus the verse “And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria” (Luke 2.2) is now made to read: “And this was the registration before Cyrenius was governor of Syria”. By this simple substitution the census is cut free from the year 6 AD – and this opens up the possibility (… probability …certainty!) that there was an earlier census. If this seems to cast a shadow on why, in that case, Luke bothers to mention Cyrenius at all, then the apologist now moves the second piece of sticking plaster into place: Cyrenius was governor of Syria twice!

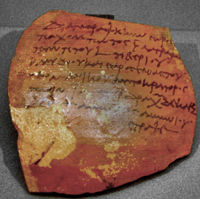

Luke refers to the census (τῆς ἀπογραφῆς) a second time – in Acts 5.36-8:

“Men of Israel, be cautious in deciding what to do with these men.

Some time ago, Theudas came forward, claiming to be somebody, and a number of men, about four hundred, joined him. But he was killed and his whole following was broken up and disappeared.

After him came Judas the Galilean at the time of the census; he induced some people to revolt under his leadership, but he too perished and his whole following was scattered.”

Far from being a “remarkably accurate historian” Luke is an alarmingly inaccurate plagiarist from Josephus!

No room – in a town full of Joseph's relatives?

Never able to concede gracefully, Christian apologists devote a lot of energy to rescuing Luke from his chronological errors by manipulation of both the text and historical evidence. Thus the verse “And this taxing was first made when Cyrenius was governor of Syria” (Luke 2.2) is now made to read: “And this was the registration before Cyrenius was governor of Syria”. By this simple substitution the census is cut free from the year 6 AD – and this opens up the possibility (… probability …certainty!) that there was an earlier census. If this seems to cast a shadow on why, in that case, Luke bothers to mention Cyrenius at all, then the apologist now moves the second piece of sticking plaster into place: Cyrenius was governor of Syria twice!

“And so it was, that, while they were there, the days were accomplished that she should be delivered. And she brought forth her firstborn son, and wrapped him in swaddling clothes, and laid him in a manger; because there was no room for them in the inn.” – Luke 2.6-7.

“But when the Child was born in Bethlehem, since Joseph could not find a lodging in that village, he took up his quarters in a certain cave near the village.” – Dialogue with Trypho, 78.

“Even my own Bethlehem, as it now is, that most venerable spot in the whole world of which the psalmist sings: the truth has sprung out of the earth, was overshadowed by a grove of Tammuz , that is of Adonis ; and in the very cave where the infant Christ had uttered His earliest cry lamentation was made for the paramour of Venus.” – Jerome to Paulinus Letter 58.3.

Curiously, we don’t hear of these uniquely privileged shepherds again!

"Parthenogenesis" – Virgin birth, a popular motif

Posthumous invention also had a hand to play. Both Plato and the Buddha were ascribed virgin births by their devoted and deluded followers. And though Apollonius of Tyana, the famous neo-Pythagorean philosopher, said he had a father, according to Philostratus (The Life of Apollonius) popular belief was that “Proteus … the god of Egypt” and Zeus himself had a hand in his conception.

The nativity: a trajectory of embellishment

“Luke’s Bethlehem story is not complementary to Matthew’s, filling in the gaps, as is often assumed. Rather, it is an irreconcilably different account from beginning to end: in story line, supporting characters, geographical and historical detail, and style. Where was Jesus born? Was it Bethlehem or Nazareth or even Sepphoris, Tiberias or Jerusalem? We cannot know for sure because the early Christians themselves apparently did not know.”

– Steve Mason, Where Was Jesus Born? The First Christmas, Biblical Archaeology Society, 2009.

Related Articles:

Luke – "Angels but no star"

* Who's the Messiah?

Etymology

Time's Up

“Your people .., shall inherit the land for ever … the sons of the alien shall be your ploughmen and your vine dressers … Men shall call you the ministers of our God. You shall eat the riches of the Gentiles … Instead of your shame there shall be a double portion…”

– Isaiah 60.21-61.7 .

How wrong can you be?

Why waste a good yarn?

That’s it! That’s Jesus!

Taxing in the Provinces

"Death for premarital sex"

“If there is a betrothed virgin, and a man meets her in the city and lies with her, then you shall bring them both out to the gate of that city, and you shall stone them to death with stones, the young woman because she did not cry for help though she was in the city, and the man because he violated his neighbour’s wife.

So you shall purge the evil from your midst.”– Deuteronomy 22:23-24.

That’s it! That’s Jesus!

Born in a Stable?

The Cave

Church Father offers evidence of Cave plus Manger

– Origen. Contra Celsus, I, 51.

Last word