Paul in Caesarea? – Trial and Error

Further adventures of the improbable Paul

Reality and the Christian dreamscape intersect in the city of Caesarea and in the persons of Felix and Festus, Roman procurators who feature both in secular history and in the fantasy called Acts of the Apostles. Neither the city nor the two men get a mention in Paul’s own epistles but then the apostle would recognize little of his “life” as purported in Acts.

Caesarea grows in the story

“So he went in and out among them at Jerusalem, preaching boldly in the name of the Lord. And he spoke and disputed against the Hellenists. But they were seeking to kill him. And when the brothers learned this, they brought him down to Caesarea and sent him off to Tarsus.” – Acts 9.28-30.

Paul’s fateful final visit to Jerusalem (he was twice advised by the Holy Spirit, no less, not to go!) turns out to be a pivotal episode.

Paul's "flight to Caesarea"

After the three failed attempts by Jews to murder Paul in Jerusalem, the clueless Roman commander, Lysias, sends Paul to Caesarea for a proper “trial”, on what will be the apostle’s fourth, climatic visit to the city. The size of Paul’s military escort for the journey is staggering:

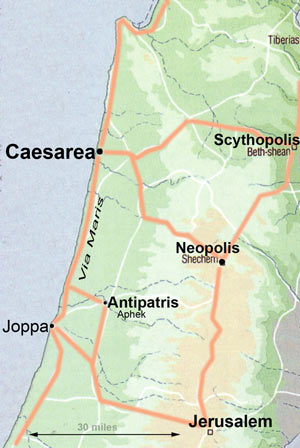

The journey from Jerusalem to Caesarea was about seventy-four miles along the route which passed through Aphek, an ancient Canaanite town renamed by Herod for his father Antipatris. It was said to be “150 stadia” (about 18 miles) from Joppa, though the town’s exact location remains in doubt.

Thirty miles a day was about the maximum speed achievable on foot. Therefore, for Paul and his imperial escort to make the distance of forty-five miles to Antipatris in a single night – even if largely a downhill march! – is a flight of fancy.

Paul before Felix?

This episode begins with Paul arriving on horseback from Jerusalem with an entire squadron of cavalry as his escort. Having travelled the previous night at the pace of four hundred foot soldiers, presumably even on horseback Paul’s party does not arrive at Caesarea until late in the day. The apostle is immediately taken before Felix, the governor, and Paul’s claimed Roman citizenship gains him a hearing, “when his accusers arrive,” which they do five days later. They are led by high priest Ananias, and, oddly (has the high priest lost his own voice?), an orator by the name of Tertullus* who is to present their case.

The charges

Paul is invited by the procurator to respond.

Paul's defence

After these “opening statements,” the case is deferred pending the arrival of Lysias from Jerusalem with “more evidence” – though in fact that never occurs. Paul remains in his “palace prison” and Lysias disappears from the story! And yet Paul’s detention is far from onerous. One oddity is that he has a centurion as a personal guard. Another is that he is “at liberty” and can receive visitors – though there’s no record that either Peter, Philip or any of the brethren came calling!

Entertaining Drusilla

Where on earth would Paul have kept his stash of cash, for heaven sake, under his prison mattress or at the local Wells Fargo office?

And did Felix really sustain a “hope for a bribe” for two years?

Trial and Error

Paul before Festus, Agrippa and Bernice?

Paul denounces the idea of being “handed over to the Jews” but Festus has not made any such threat. He has specifically spoken of a trial “before me” – not a Jewish court (Acts 25.9.) And just what is Paul appealling to Caesar about – nebulous charges that have already been determined as merely a matter of religion? (Acts 23.29; 25.19; 25.26-27). A verdict of not guilty? (Acts 26.32). An unlawful punishment which he hasn’t received? (Acts 25.16). Since he acknowledges that he is already before Caesar’s court, what can he possibly gain from the court of the capricious tyrant Nero – which, if we believe the mythology, did indeed result in his beheading! But we are not talking here of history but of theatre.

Enter Agrippa

With this, the stage is set for the next fantasy – a rip-roaring voyage to Rome.

End game - The Augustan Band (Cohors I Augusta)

“When Cumanus heard of this action of theirs, he took the band of Sebaste [Greek ‘Augustus’], with four regiments of footmen, and armed the Samaritans, and marched out against the Jews, and caught them, and slew many of them, and took a great number of them alive.” – Antiquities, 20.122.”

PS: Dating Paul – Province Cilicia?

– N. Sitwell, Roman Roads in Europe, p200/1.

- Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 15; Jewish War I.

- Avner Raban, Kenneth Holum, Caesarea Maritima – A Retrospective after Two Millennia (Brill, 1995)

- Eusebius, The Martyrs of Palestine (Digireads, 2005)

- Ehud Netzer, The Architecture of Herod, the Great Builder (Baker, 2008)

- Lee I. Levine, “Roman Caesarea: An Archaeological-Topographical Study.” Qedem II, 1975

- M. Grant, Herod the Great (McGraw-Hill, 1971)

- Jerome Murphy-O’Connor, The Holy Land (OUP, 1986)

Felix - slave who lived like a king?

Herodian retreat

Where DID they get their ideas?

The Gods of Caesarea

MITHRA

SERAPIS

APHRODITE

HYGIEIA

TYCHE

The Tiberium

Doing Time

Prison 1

Prison 2

Prison 3

Paul's "12 day wonder"