The Improbable Paul

The making of a Super Apostle!

Paul – inventor or invention?

One curiosity about Paul’s letters is that they survived at all. Polemical and often scathing in tone one wonders why the recipients kept them safe for generations, copying hostile texts not cited by the later gospel writers and neglected by the brethren at large for a century or more. Not until Marcion, the heretical bishop from Pontus, published several Pauline letters in the middle decades of the 2nd century were the epistles acknowledged or quoted.

Who, one wonders, in Paul’s faction-riven churches, decided to regard the apostle’s rambling missives as tantamount to “scripture”, on a par with the Tanakh, the only other sacred writings they might have known? Why would early Pauline converts have hung on to his letters anyway – had they not just learned from the master that the existing world would soon pass away? Who, in a time of apocalyptic anticipation, would have been so motivated (and able) to gather a collection letters purportedly sent everywhere from Rome to Galatia?

The truth is that Paul’s letters are not what they appear to be – and more to the point, not when they appear to be.

Genuine Fakes

“We beseech you, brethren … that you not be soon shaken in mind, or be troubled, neither by spirit, nor by word, nor by letter supposedly from us, as that the day of Christ is at hand. Let no man deceive you by any means.” – 2 Thessalonians 2.1,3.

Paul’s “Romans“, 7111 words in the original Greek and about 9,400 words in modern English, would have been the longest and most expensive “letter” ever written in the ancient world. 1 Corinthians, at just shy of seven thousand words, is second only to Romans as the longest of the epistles and is highly unlikely to have been a genuine letter. The epistles of Seneca, for comparison, average about a thousand words, and those of Pliny are of a similar length.

In comparison, the longest letter of Cicero (xv, to P. Lentulus Spinther in Cilicia, written in Rome, 54 BC) has 5200 words. And yet Cicero was a wealthy Roman aristocrat, a consul of Rome, who was more than able to afford secretaries and scribes. In contrast Paul was supposedly a peripatetic missionary, often in dire straits (“poor, yet making many rich” – 2 Corinthians 6.10). Could Paul – or his fledgling “churches” – really have afforded his verbose and truculent letters – and would they have regarded them as an appropriate use of their money?

Whilst so much ancient writing is fragmentary, in the Pauline epistles we have a comprehensive corpus of doctrine, meeting all the needs of a functioning Church. Though many curious and suspicious gaps obscure the life of the evangelist himself, his theology is complete and entire.

That letters were forged in the name of Paul, and over an extensive period of time, is beyond doubt. 3 Corinthians, for example – part of the New Testament apocrypha – is an anti-gnostic forgery penned by Catholics in the late 2nd century. So, too, are purportedly Pauline letters to the Laodiceans and Alexandrians. The witness for this is no hostile critic of Christianity but the earliest list of “orthodox” texts, named for its 18th century Italian discoverer Muratori. This document includes the comment:

“Moreover there is in circulation an epistle to the Laodiceans, and another to the Alexandrians, forged under the name of Paul.”

Forged or “pseudepigraphical” texts were not a 2nd century innovation. Every book of the Bible has a spurious purported author. As Bart Ehrman notes, “Paul” himself warned of false authorship in his own name:

“Either 2 Thessalonians is from Paul’s own hand and he knows of a forgery that is floating around in his name, or 2 Thessalonians is not from Paul’s hand and is itself a forgery. This makes a rock-solid argument that there were Pauline forgeries in the 1st century.”

– Bart Ehrman, Peter, Paul and Mary Magdalene, p93.

“Paul the Missionary” – an impostor

None of the pegs which purport to attach Paul to the secular history of the middle years of the 1st century can withstand scrutiny (not Aquila and Priscilla, not Gallio, not Aretas, not Nero). Oddly, in a compendium of letters amounting to about 44,000 words, nothing unambiguously “dates” the writer.

Did Paul really evangelize among the Gentiles?

A simple yet undeniable truth is that NOT ONE of the early Christian churches in the major cities of the Roman world owed anything to a pioneering apostle called Paul. Without exception, the circumstances in which these churches emerged, and the personalities involved, are quite unknown. Manifestly, no charismatic founder was required for Hellenized Jews and Judaizing pagans to synthesize a revised Judaism for an age which despised Jewish exclusivity and viewed with alarm the messianic ambition of Judaism.

Evidently, the foundational events were unknown even as early as the 2nd century – or were deliberately obscured in the collective memory of the Church to hide less heroic and more mundane origins. That Paul did not “found churches” casts further doubt on his grand missionary journeys. They are demonstrably fables of an idealized progenitor, an iconic, heroic and palpably unreal figure.

| Cyprus | Galatia | Macedonia | Greece | Rome |

But the evangelists were not original minds. “Paul the Apostle” was plagiarized from earlier sources and part of the Lukan creation may have been a minor figure from the early years of the 2nd century, similar to – if not indeed identical with – the heretic teacher “Paul of Antioch,” whose “skill in argument” influenced, but failed to convince, Origen as a boy (Eusebius, History of the Church, 6.2.13-14).

In any event, if the epistles of Paul are fake, if the missionary journeys of Paul are fake, what confidence can we have that Paul himself has any integrity as an historical character?

The aggrandizing of Paul – “Dr Luke” builds a proselytizing apostle

“Luke, the author of Acts, was something of a novelist and could not resist introducing the colourful characters of Herod and his sister Berenice, and giving his hero Paul an opportunity to harangue them and win their respectful attention.“

– Hyam Maccoby, The Mythmaker, p171.

A biography of Paul, gleaned solely from his epistles, would be a slender volume indeed (it would confine our letter-writing hero to the decade of the 50s and an Aegean triangle Ephesus- Corinth- Thessalonika). Most of what we think we know about Paul comes not from his own writings but from Acts, the great work of Catholic harmonization, written, we are assured, by “Luke”, the sometime travelling companion of Paul.

But curiously, Paul himself says nothing of “Doctor” Luke – other than three passing mentions in epistles deemed “inauthentic” by most scholars. It is salutary to note that the many “facts” about Paul found in Acts gain no support at all from the Pauline epistles. In most cases, the “facts” are starkly contradicted by the man himself or undermined by common sense.

So just what was Dr Luke up to? Essentially, the author of Acts fabricated a “history of the Church” which both legitimized the power base of several key bishoprics and transformed who – perhaps – was an obscure theorist based in Asia Minor or Syria into a model Jewish convert, amiable team-player and Roman-friendly evangelist.

Claims designed to give Paul impeccable “Jewish” credentials:

– Paul was formerly known as Saul? (Acts 7.58 et al) Nothing in Paul’s epistles says this but of course the name Saul belonged to the first Jewish king. How appropriate that a “primary Jew” should become a primary Christian. Paul will come to symbolise the continuity between Judaism and Christianity. As Saul he mistook the Christians for heretics. But once the truth had been revealed to him – glory be! – he of all people realized that Jesus had been the one foretold by the prophets and that the Christians were the true Judaism.

– Paul studied under Gamaliel, the great Pharisaic teacher? (Acts 22.3) Not a claim Paul makes but the assertion serves to emphasize Paul’s prowess in Judaism. All the better that a peerless Judaist should become the paramount apostle of Christ. It’s worth noting that the claim can scarcely be true – Gamaliel, a senior Rabban, taught advanced students not children.

To strengthen its point Acts also has Paul speak Hebrew (22.2), a talent not vouchsafed by Paul’s own writings where he habitually quotes from the Greek Septuagint not the Hebrew scriptures.

– Paul is a tentmaker? (Acts 18.3) Not said by Paul but a “good Jew”, even a Pharisee, unless independently wealthy, probably had a trade. Paul’s work record is very patchy – his “ministry” seems to have paid for his meandering existence. Twenty years in Jerusalem and he seems never to have worked. It seems his faith provided his reward:

“But to him who does not work but believes on Him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is accounted for righteousness.” – Romans 4.5.

– Paul was a religious policeman, a heresy hunter hired by the High Priests? (Acts 9.1,14,21) Hardly the tale that Paul reports although he does say “how intensely I persecuted the church of God and tried to destroy it” (Galatians 1.13) a claim echoed elsewhere (Philippians 3.6; 1 Corinthians 15.9).

Dr Luke even implies that Paul was a member of the Jewish council, the Sanhedrin, which reached decisions by voting: “I put many of the saints in prison, and when they were put to death, I cast my vote against them.” (Acts 26.10).

But just what does Paul mean by persecuted? Shorn of the lurid amplification of Acts – which cannot stand close scrutiny – this is no more than verbal hyperbole and may well be Catholic redaction, itself based on the yarn in Acts.

“Intensely – kath’hyperbolên – indicates intensity of commitment not violence.“

– O’Connor, Paul, a Critical Life, p67.

In Acts 5.34-40 “Gamaliel, a doctor of the law” successfully persuades the Jewish council to release the disciples and cease persecution “just in case” the disciples were doing God’s work – which makes it all the more odd that immediately after this, “certain of the synagogue” (Acts 6.9) convince the council to reverse its policy and not just beat but stone to death new man Stephen!

It is this incident which introduces Paul’s career as a “persecutor” and yet Paul is said to have been a student of none other than the Gamaliel who had urged caution! (Acts 22.3).

– Paul was a circumciser, who performed the deed on Timothy? (Acts 16.3). Inexplicably Paul circumcises his acolyte “because of the Jews“. Yet Paul says nothing in his letters to confirm this, even though he mentions Timothy several times. But what makes the claim palpably ridiculous is Paul’s fierce denunciation of circumcision in Galatians:

“Indeed I, Paul, say to you that if you become circumcised, Christ will profit you nothing! And I testify again to every man who becomes circumcised that he is a debtor to keep the whole law. You have become estranged from Christ, you who attempt to be justified by law; you have fallen from grace!“

– Galatians 5.2-4.

Claims designed to bring Paul “on side” with the team of disciples:

– Paul experienced an epiphany on the road to Damascus? (Acts 9.3-8; Acts 22.6-11; Acts 26.12-18).

Although Acts repeats this tale three times (and each time rather differently!) the classic encounter with the risen Christ has no place in Paul’s own epistles. Paul speaks of a “revelation of the Son” but notably avoids giving any details of when or where. Paul stresses, if anything, his being “chosen while in the womb” (Galatians 1.15,16) – which rather detracts from any later encounter.

Paul does write (oddly, using the third person) of an “out of body” experience, though it bears nothing in common with the Damascene road show:

“I know a man in Christ who fourteen years ago – whether in the body I do not know, or whether out of the body I do not know, God knows – such a one was caught up to the third heaven … he was caught up into Paradise and heard inexpressible words, which it is not lawful for a man to utter.“

– 2 Corinthians 12.2-4.

Inspiration for the “Damascus connection” quite probably came from the yarn about Elijah in the book of Kings. The prophet orchestrates the murder of rival priests and, similarly, Paul “wastes the church.” Elijah receives an epiphany in the desert and so, too, does Paul. And God’s instruction to Elijah? “The Lord said to him, ‘Go back … to the Desert of Damascus.’ ” (1 Kings 19.15). Paul, of course, is led into Damascus.

When Paul does write of Damascus it is not about the king of heaven but of King Aretas and an attempt to arrest him (2 Corinthians 11.32).

But as a “team building” yarn the Damascene road anecdote allows an early Christian – Ananias*– to intercede with the apostles on behalf of Paul and off they go to Jerusalem to meet the rest of the gang. Paul himself says he went to Arabia and emphasizes that he saw no one.

As a nice little touch, when the blinded “Saul” waits out his three days in Damascus before Ananias delivers the Holy Spirit, he stays at the house of a Judas (Acts 9.11), a name symbolic of the entire Jewish race, of course – just like his namesake Judas Iscariot.

– Paul took the edict from James on food prohibitions to the Gentiles?

“And after they had held their peace, James answered, saying, Men and brethren, hearken unto me … my sentence is, that we trouble not them, which from among the Gentiles are turned to God. But that we write unto them, that they abstain from pollutions of idols, and from fornication, and from things strangled, and from blood.” – Acts 15.13-20.

In Romans Paul writes that he is “persuaded by the Lord Jesus that there is nothing unclean of itself” (Romans 14.14) – and he makes no reference here to any apostle called James! An idol, says Paul, is “nothing in the world” (1 Corinthians 8.4) and food offered to an idol is certainly not defiled. But Paul is concerned that an insouciant attitude will have an adverse effect on “weak” Christians and so he cautions the “strong” brethren to restrain themselves when necessary.

Manifestly, Paul’s policy owes nothing to any edict from James on food prohibitions but is sheer pragmatism.

– Paul went to Jerusalem with famine relief?

Another curious yarn from Acts involves prophets from Jerusalem visiting Antioch. One of them, Agabus by name, predicts famine. Even though Agabus says specifically that the famine will be “world-wide” the brethren of Antioch decide to raise gifts for the brothers of Judaea, to be delivered by Paul and Barnabas.

“Barnabas … found Saul and brought him to Antioch … Some prophets came down from Jerusalem … One of them, named Agabus … through the Spirit predicted that a severe famine would spread over the entire Roman world. This happened during the reign of Claudius. The disciples, each according to his ability, decided to provide help for the brothers living in Judea. This they did, sending their gift to the elders by Barnabas and Saul.” – Acts 11.25-30.

Why the partiality – were those to be struck by famine in Syria itself of no concern?

But of course there was no famine “spread over the entire Roman world.” Roman historians regularly attest to localized droughts and food shortages in various provinces of the empire, a different matter entirely. The soothsayer Agabus is wrong about the famine, as he is later in Acts when he predicts Paul will be “bound by his own belt and handed over to the Gentiles by the Jews” (Acts 21.10). When Luke writes that particular part of the fable he has the Jews try to kill Paul and his hero is rescued by Roman soldiers!

But the most damning comment about “famine relief” comes from Paul himself – he says not a word! In fact, Paul got into raising money “for the saints” from his earliest mission:

“Now concerning the collection for the saints: you should follow the directions I gave to the churches of Galatia. On the first day of the week, each of you is to put aside and save whatever extra you earn, so that collections need not be taken when I come.” – 1 Corinthians 16.1-4.

Later, in Romans, the collection is to be for the “poor among the saints”:

“But now, I am going to Jerusalem serving the saints. For Macedonia and Achaia have been pleased to make a contribution for the poor among the saints in Jerusalem.” – Romans 15.25-26.

The missionary who supposedly travelled the world knows nothing of any universal famine – and his fund-raising has a rather more personal motive. As he rationalizes to the Corinthians:

“If we have sown spiritual goods among you, is it too much if we reap your material benefits?“

– 1 Corinthians 9.11.

It is worth noting that neither Paul (nor any of the other epistle writers for that matter) ever mentions the disciples of Jesus. Paul identifies Peter and James NOT as disciples of Jesus but as apostles like himself. Disciple implies a guru to follow, apostle does not.

Claims designed to make Paul more acceptable to the Roman world:

– Paul is a Roman citizen? Paul himself never claims this and a zealously orthodox Jew meeting the civic requirements of Roman citizenship – such as honoring the state gods – is a most unlikely construct. Equally unlikely is that “Roman” Paul would have acquiesced in so many thrashings from the Jews.

As a story element “Roman citizenship” gets Paul out of jail in Philippi after a single night – yet in Caesarea Paul languishes in jail for two years! Only then does Paul’s “Roman” status move the story on to the required climax in Rome.

– Paul is from Tarsus? Paul himself never says this either, but the city was noted as an “intellectual” centre of the Roman world. Augustus actually appointed a stoic philosopher, Athenodorus of Tarsus, as governor of Cilicia. Paul is also made to claim to be a “Pharisee, a son of a Pharisee” (Acts 23.6) – which could not be true if Paul really was a Jew from the diaspora – there were no Pharisees in the diaspora! Jerome (Commentaria in Epistolam ad Philemon 23.4) says Paul was from Galilee.

– Paul went on a first mission to Cyprus? From Paul, not a word about Cyprus, nor is there any “epistle to the Paphosians”. But the yarn conveniently brings Paul before a Roman governor and facilitates a prestigious conversion. The veracity of such a claim is belied by the lack of any evidence of Christianity on the island for centuries.

– Paul lived and evangelized in Rome itself? The happy ending to Acts has Paul holding court in the imperial city – yet Paul’s final epistle, Romans, has the great apostle anticipating a mission to Spain. The so-called “prison epistles”, said to have been written in Rome, are used to support a variety of conflicting scenarios, but they are late and fake.

In the hands of “Dr Luke” Paul is moulded into the perfect “apostle to the Gentiles.” But just who (or what) was the kernel about which the story teller wove his edifying tale of missionary triumph?

How DID “Paul” get started? The Charlatan Hypothesis

“The cities of the Graeco-Roman world were infested by charlatans who made a good living out of pious promises supported by fake miracles.”

– Murphy O’Connor, Paul, His Story, p28/9.

Sometime, in that period between the ruin of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 AD and the final destruction of the Jewish kingdom in 135 AD, communities of Hellenized Jews, together with their God-fearing Gentile sympathizers, metamorphosed into revisionist cliques of Judaism in the synagogues of the diaspora. The tiny handful of literate members, following the practice of the erstwhile Temple scribes, doubtless on rare occasions (because of the expense) took to writing hand-delivered letters of encouragement and recrimination to each other. Diatribes may well have been flyposted in public places, in a manner echoed many centuries later in the anonymous pasquines of the Spanish colonial empire.

But more effective than any letter in raising a following would have been public performances in forums and village gatherings, where artful chicanery would suspend the laws of physics and “malevolent spirits”, supposedly the cause of sickness, would be expelled by “exorcism“. Such mighty works pepper the New Testament. A major feature of Jesus’ ministry is portrayed as curing people of demonic possession through exorcism – most famously, the “demons into pigs” episode at Gadara (Mark 5.7-13). It was this power to expel devils and unclean spirits that JC gave to the twelve when he sent them on their first mission:

“He called his twelve disciples to him and gave them authority to drive out unclean spirits and to heal every disease and sickness.” – Matthew 10.1.

Perhaps, in the real world, a clever and ambitious scribe, in a city like Ephesus or Antioch, performed a “healing” in the name of Christ. The trick would have been child’s play. A stooge (a Timothy or a Titus), planted in the audience, would feign a malady and then pretend to be healed. This venerable scam, so simple yet so effective among those desperate for remedies, remains a standard item on the charlatan’s menu of “signs and wonders”.

With the streets of every ancient city thronging with fearfully superstitious people, our “healer” eventually attracted the interest of desperate Roman matrons (a Priscilla or a Lydia?) able to pay for his “Jewish” cures and lucky charms. His words would have acquired a sought after “authority”, opening up the opportunity to write (or dictate) letters, offering unsolicited guidance for faith and appealling for funds. Perhaps our showman called himself Paul – who can say. But once Pauline authorship became the touchstone of authoritative teaching, every contending Christian faction claimed Paul for themselves and wrote in his name.

An indication that such a scenario may be more than speculation is provided by a 4th century churchman – Epiphanius.

The Ebionites castigate a certain adventurer called Paul

The source is late but the story is intriguing. Epiphanius, 4th century bishop of Salamis with a large sphere of influence in the eastern Mediterranean, reported on the Ebionites in his magnum opus on heresies.

According to Epiphanius the Ebionites said that Paul had been the offspring of non-Jewish parents and had himself converted to Judaism while in Tarsus. He had never studied with Gamaliel or been a Pharisee but rather had attached himself to the Sadducee High Priest as some sort of henchman. When he was passed over for advancement Paul broke with the High Priest and retaliated by setting up his own cult, a concoction of Hellenistic dying/reborn sun-god motifs blended with Jewish scripture and tradition. In short, Paul was a Hellenistic adventure of undistinguished background.

The Ebionites were declared heretics by rabbis of the Jewish establishment, probably no earlier than 135 AD.

Simon Magus – primordial Paul?

“[Simon of Josephus/Simon of Acts] … upon the hypothesis that Josephus is not misinformed as to his being a Cypriot Jew; for otherwise the time, the name, the profession, and the wickedness of them both, would strongly incline one to believe them the very same.” – William Whiston, The Works of Josephus.

“Atomos” is Greek and — when referring to a person — must be translated as “tiny one”; or in Latin, “Paul”! Simon Atomos is Simon Paul!” – Hermann Detering, Journal of Higher Criticism

Another enigmatic character inhabits the twilight world of early Christianity, the “apostle of the heretics,” Simon Magus (the Magician).

Witness to Simon’s existence is found in Josephus’ Antiquities 20.7.2, where a friend of Felix, the procurator, “Simon, a Jew from Cyprus, who pretended to be a magician,” is instrumental in persuading Druscilla (the sister of Herod Agrippa II) to divorce her husband and marry Felix. Felix governed the Jews between 52-60 AD (the “time of Paul”). In some manuscripts the name “Atomos” replaces Simon.

Acts relates its own yarn about Simon the Magician (like Paul, he is unmentioned in the Gospels).

“They all gave heed, from the least to the greatest, saying, ‘This man is the great power of God.’ And to him they had regard, because that of long time he had bewitched them with sorceries.“

– Acts 8.10,11.

The following dozen verses of Acts packs in a host of nonsense: Simon’s conversion by the “signs and wonders” of Philip the deacon; the arrival of the heavies Peter and John with the Holy Spirit; Simon’s offer of money for the power of Holy Spirit; Peter’s curse and Simon’s final plea for forgiveness.

Simon clearly had awesome bewitching power. For centuries, the Christians kept up the attacks, naming him the “father of all heresies” and weaving into the fantasy Helen of Troy and/or a prostitute called Helena, Nero (who else!) and a battle of magic with Peter. His name was stigmatized by the Christians in the sin of simony (the buying and selling of ecclesiastical favours) and Gnostics were characterized as “Simonians.“

Acts reprises the “Jewish magician of Cyprus” story cribbed from Josephus on two further occasions. In the first episode (Acts 13.6-12) the sorcerer’s name is switched to “Bar Jesus / Elymas by interpretation.” Paul blinds his rival with a holy incantation. This little drama will later get transferred to Rome (in the Clementine Recognitions) where Simon’s adversary becomes Peter rather than Paul (and Paul gets blended into Simon!).

The second episode is Acts 24.24-26 where Felix and his new wife Druscilla are brought back on stage. Paul, a prisoner, nonetheless induces “trembling” in the tough Roman governor by the force of his sermonizing (!). Ludicrously, Felix, probably the richest as well as most powerful man in the province, “hopes for a bribe” from the apostle locked in his own prison (which of course reintroduces the element of venality attached to Simon)!

Paul re-made

The history of Josephus has a missing section after Antiquities 20.7. – one of those “curious” lacunas that obscures crucial episodes in the Christian story (like the fifth book of Tacitus’ Annals, covering the years 29-31, and books eleven through to sixteen covering the years 47-66).

How convenient for those who wish to obscure Christian origins!

However, for all the manipulations and flip-flops with the texts it may well be the case that at an early stage in the development of the character styled Paul, a “Simon Paul” confronted a “Simon Peter”. But as the Catholics successfully assimilated their Marcionite and Gnostic opponents the legendary Paul was reworked in Acts of the Apostles. He acquired a pre-conversion persona inspired by the Saulus mentioned by Josephus. Post-Damascus, he acquired an harmonious, almost subordinate relationship with the apostles in Jerusalem.

By the end of the 2nd century prophecies of the coming of Paul within Jewish scripture were being identified by Christian theorists, in a manner painfully reminiscent of the concoctions teased out for Jesus himself. Tertullian found Paul “foreseen” in the book of Genesis:

“Now if anyone can pretend that he is Christ, how much more might a man profess to be an apostle of Christ! But still… even the book of Genesis so long ago promised me the Apostle Paul. Jacob … exclaimed, ‘Benjamin shall ravin as a wolf; in the morning He shall devour the prey, and at night he shall impart nourishment.’

He foresaw that Paul would arise out of the tribe of Benjamin … in the early period of his life he would devastate the Lord’s sheep, as a persecutor of the churches; but in the evening he would give them nourishment …as the teacher of the Gentiles.

Then, again, in [king] Saul’s conduct towards David, exhibited first in violent persecution of him, and then in remorse and reparation, on his receiving from him good for evil, we have nothing else than an anticipation of Paul in Saul.”

– Tertullian, Against Marcion, 5.1

If the “coming of Paul” was an event foretold in scripture then the search for an historic kernel becomes rather academic. Scripture becomes the maquette upon which a drama of missionary derring-do is built. With cultural drift (as evidenced at Miletus) much of “Paul’s teaching” was a reality anyway.

Abandonment of certain traditional rules allowed Jews to prosper in a cosmopolitan world, particularly after three anti-Roman wars had turned the Jews into pariahs. Doctrinal as well as practical compromise became acceptable.

Judaism’s perverse food prohibitions were, perhaps, the first anti-social behaviour to be relaxed. Attendance at the race track or the theatre was surely not harmful to God? If many “god-fearers” were repulsed by circumcision “as it was not their custom,” why bar them from the local synagogue? And certainly, all might contribute to “collections for the saints.”

The replacement of an odious notion of a “chosen people” with a more inclusive doctrine that “all might be saved” by the Jewish God was a natural, not a miraculous, development. The theological novelty – a self-sacrificing redeemer “in times past” replacing Judaism’s anticipated world conqueror, was reassuring to authority that at least some Christ-cults were not aiming at sedition and made the corridors of power accessible to God’s vicars on earth.

Priestly ambition to homogenize the variant factions or eliminate rivals drove forward the polemics of the so-called epistles until a universal, Catholic harmony was achieved. What we have in Paul is not a super-apostle but a superlative fraud.

* Where DID they get their ideas from?

Instrumental in the conversion of the “persecutor Saul” into the apostle Paul was a certain “Ananias” (at least according to the book of Acts – the epistles are silent).

How very curious that in the history of the Jews preserved in Josephus the no less significant conversion of Izates, the king of Adiabene, to Judaism, was also the work of a certain “Ananias.”

How very curious that Izates’ conversion to Judaism occurred at around the same time purported for Paul’s conversion to Christianity, and also involved a very “Pauline” wrangle over the merits of circumcision. In the case of Izates his quandary was resolved in favour of circumcision as the “more perfect” conversion. Contrariwise, Paul’s instruction to his converts was that circumcision was of “no consequence”. Like the Jews of Damascus, the nobles of Adiabene tried but failed to kill the renegade convert from the old religion.

All a coincidence?

History

“Now during the time when Izates lived at Charax Spasini, a certain Jewish merchant named Ananias got among the king’s women and taught them to worship God according to the Jewish religion. Through them he became known to Izates, whom he persuaded in like manner…

When Izates perceived that his mother was highly pleased with the Jewish customs, he was eager to embrace them entirely ; and as he supposed that he could not be thoroughly a Jew unless he were circumcised, he was ready to have it done …

Now when the king’s brother, Monobazus, and his other kindred, saw how Izates, by his piety to God, was become greatly esteemed by all men, they also had a desire to leave the religion of their country, and to embrace the customs of the Jews,”

– Josephus, Antiquities 20.2.3-4.1.

Fantasy

“Now there was a disciple at Damascus named Ananias. The Lord said to him in a vision, “Ananias … go to the street called Straight, and at the house of Judas look for a man of Tarsus named Saul … He is a chosen instrument of mine to carry my name before the Gentiles and kings and the children of Israel … “

So Ananias departed and entered the house. And laying his hands on him he said, “Brother Saul, the Lord Jesus who appeared to you on the road by which you came has sent me so that you may regain your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit.”

And immediately something like scales fell from his eyes, and he regained his sight. Then he rose and was baptized; and taking food, he was strengthened. For some days he was with the disciples at Damascus. And immediately he proclaimed Jesus in the synagogues, saying, “He is the Son of God.”

– Acts 9.10-20.

* Acts 22.12 (unlike Acts 9.10) describes Ananias not as a disciple but as “a devout observer of the law and highly respected by all the Jews” which makes the subsequent murderous intent of the local Jews towards Paul all the more ludicrous. The third re-telling of the yarn, Acts 26, avoids mentioning Ananias at all.

PS: Pauline epistles: Before or after destruction of the Temple?

“God’s judgment has come upon the Jews at last!” – 1 Thessalonians 2.16.

Several passages in the Pauline epistles hint at an origin after, not before, the destruction of the Jewish Temple in 70 AD:

“Because of unbelief they [the Jews] were broken off, and you stand by faith. Do not be haughty, but fear.

For if God did not spare the natural branches, He may not spare you either.

Therefore consider the goodness and severity of God:

on those who fell, severity; but toward you, goodness.” – Romans 11.22.

“Do you not know that YOU are God’s Temple and that God’s Spirit dwells in you?

If anyone destroys God’s Temple, God will destroy him.

For God’s Temple is holy, and YOU are that temple.“ – 1 Corinthians 3.16-17.“The day of Christ … will not come unless … the man of sin is revealed, the son of perdition, who opposes and exalts himself above all that is called God or that is worshipped, so that he sits as God in the Temple of God, showing himself that he is God.” – 2 Thessalonians 2.2-4.

From these passages, it is clear that the “severity” of God has already fallen on the Jews. This may refer to the war of 66-70 and the carnage which ended that conflict. On the other hand, the war of 133-135 also comes into focus. If the “son of perdition” worshipped “as a god in the Temple of God” is a reference to the statues of Emperor Hadrian erected on Temple Mount, then the epistles are post-135.

Sources:

Bart Ehrman, Peter, Paul and Mary Magdalene (OUP, 2006)

J. Stobart, The Glory that was Greece (Sidgwick & Jackson, 1964)

W. Keller, The Bible as History (Hodder & Stoughton, 1969)

A. Woods, Paul of Tarsus, an Enigma Enshrouded in a Mystery (Woods, 2005)

J. Murphy-O’Connor, Paul, a Critical Life (Clarendon, 1996)

J. Finegan, Light from the Ancient Past (Kessinger, 2007)

A.N. Wilson, Paul-The Mind of the Apostle (Sinclair-Stevenson, 1997)

Hermann Detering, The Falsified Paul, Early Christianity in the Twilight (Journal of Higher Criticism, 2003)

No, No – NOT the Comfy Chair!

“Nothing in his letters suggests that Paul had any official standing in his treatment of Christians …

In opposition to what Luke says, Paul could not have used arrest, torture or imprisonment … but … every time Christians went to the synagogue, they laid themselves open to an abrasive challenge from Paul.”

– Murphy O’Connor, Paul, His Story, p19.

Paul – “a man of FEW words”?

“But he who was made sufficient to be a minister of the New Testament, not of the letter, but of the Spirit, that is Paul, did not write to all the churches which he had instructed and to those to which he wrote he sent but few lines.”

– Church Father Origen, quoted by Eusebius, The History of The Church, 6.25.7.

Real world

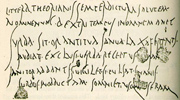

A genuine 1st century letter – Papyrus 356, British Museum

This letter – about fifty words – was recovered from Egypt. It is written in koine Greek, like much of the New Testament, and begins and ends with greetings.

“The composition of a letter of the length of 2 Timothy demanded of the ancient art of writing not hours but days of laborious work.“

– J.J. Jeremias, Die Pastoralbriefe, 5.

Paul – so Jewish

In the epistles Paul tells us almost no personal details, other than to obsess about his Jewishness:

a way of life in Judaism

advanced in study of Judaism

zealous for Jewish traditions

– Galatians 1.13-14.a Hebrew

an Israelite

a descendant from Abraham

– 2 Corinthians 11.22.a Hebrew of Hebrews

of the tribe of Benjamin

circumcised on 8th day

a Pharisee

– Philippians 3.5.

But should we believe any of this when the same “Paul” tells us that “to the Jews I became as a Jew … to them without law, as without law … to the weak became I weak … I am made all things to all men.”

– 1 Corinthians 9.20-23.

Beaten by rods?

“Thrice was I beaten with rods” (2 Corinthians 11.25).

The various ranks of Roman magistrates (aediles through to consuls) were entitled to bodyguards called lictors who carried buddles of birch rods (often with one or two axes). The bundles (fasces) were primarily symbols of the magistrate’s authority.

A lictor could be directed by his magistrate to inflict a punishment. But where, when and why Paul might have received such treatment is impossible to say.

On the other hand, the reference is almost certainly purely symbolic, calculated to resonate with a Roman, rather than a Jewish, audience.

Religious propaganda in peasant society

“Pasquines were, in effect, political and social siege weapons skillfully used by both the powerful and the weak.

They were always handwritten and were seldom produced in multiple copies, the authors relying on word of mouth to multiply the effects of their insults or charges.

Pasquines were almost always placed on the walls of public places.“

– Kenneth Andrien The Human Tradition in Colonial Latin America, 2002.

– Graffiti on a Pompeian wall quotes the poets.

Uncertain ground

“When we try to get behind Marcion to envisage the formation and history of the Pauline corpus before his time we are on uncertain ground.“

– F. F. Bruce, Peakes Commentary on the Bible, p935.

Paul in Cyprus? Not a chance

“Luke … presents Paul and Barnabas going first to Cyprus, and thence into the southern part of central Asia Minor.

A close analysis of this account brings to light so many improbabilities that it becomes impossible to accord it any real confidence.”

– Murphy O’Connor, Paul, His Story, p44.

A haircut vow? But wasn’t Paul bald?

“Paul … took his leave of the brethren, and sailed thence for Syria and with him Priscilla and Aquila … having shorn his head in Cenchraea for he had a vow.” – Acts 18.18.

Paul’s “vow” before leaving Corinth is curious indeed. Had Paul not set aside the Law of Judaism? The shaving of his head, perhaps beginning or ending the vow of a Nazir, surely had no place in the new Christ cult.

Perhaps he was copying the priests of Isis?!

Inspiration?

Equally curious is that Josephus, in his history, having introduced Aquila, governor of Alexandria, says that when Agrippa reached Jerusalem he “ordained that many of the Nazirites should have their head shorn.” – Antiquities 19.6.1.

Just another coincidence?

Acts

The core of the Pauline myth is to be found in just a few verses of the “confessional statement” in the book of Acts:

“When they heard him speak to them in Hebrew, they became very quiet. Then Paul said:

“I am a Jew, born in Tarsus of Cilicia, but brought up in this city. Under Gamaliel I was thoroughly trained in the law of our fathers and was just as zealous for God as any of you are today.

I persecuted the followers of this Way to their death, arresting both men and women and throwing them into prison, as also the high priest and all the Council can testify.

I even obtained letters from them to their brothers in Damascus, and went there to bring these people as prisoners to Jerusalem to be punished.”

– Acts 22.2-5.

Parallel yarns

Simon and Paul try to “please men.”

Simon and Paul have visions.

Simon and Paul perform miracles.

Simon and Paul succeed as missionaries.

Simon and Paul oppose the law.

Simon and Paul offer salvation.

Simon and Paul persecute the saints.

Simon and Paul interpret the Cross

Simon and Paul share disease/ humility

Simon and Paul change their appearances

Simon and Paul go to Rome in reign of Claudius.

– Hermann Detering The Dutch Radical Approach to the Pauline Epistles

Evidence of the makeover – the tensions of “Paul”

Paul is pro-Law?

“For not the hearers of the law are just before God, but the doers of the law shall be justified.”

– Romans 2.13.

“Do we then make void the law through faith? God forbid: yea, we establish the law.“

– Romans 3.31.

“Wherefore the law is holy, and the commandment holy, and just, and good.“

– Romans 7.12.

“But this I confess unto thee, that after the way which they call heresy, so worship I the God of my fathers, believing all things which are written in the law and in the prophets.” – Acts 24.14.

Paul is anti-Law?

“Christ hath redeemed us from the curse of the law, being made a curse for us: for it is written, Cursed is every one that hangeth on a tree.” – Galatians 3.13.

“Therefore by the deeds of the law there shall no flesh be justified in his sight: for by the law is the knowledge of sin … Therefore we conclude that a man is justified by faith without the deeds of the law.” – Romans 3:20,28

“But now we are delivered from the law, that being dead wherein we were held; that we should serve in newness of spirit, and not in the oldness of the letter.” – Romans 7.6.

“For Christ is the end of the law for righteousness to every one that believeth.” – Romans 10.4

The Jews of Miletus

The Jews adapted happily to Hellenistic culture in Asia Minor.

At Miletus, connected by a Sacred Way to the Temple of Apollo at nearby Didyma, the “Jews and God-fearers” had reserved seats in the fifth row of the theatre – as an extant inscription attests.

Evidence of Jewish assimilation of Hellenism, cut in stone.

Who sits as God in the Temple of God?

Hadrianic temple on Temple Mount – Dura Europa fresco.

An equestrian statue of Hadrian stood nearby. Did Hadrian exalt himself “above all that is called God“?